Special Make-Up Effects Artist Howard Berger

Interview by Jonathan Thomas

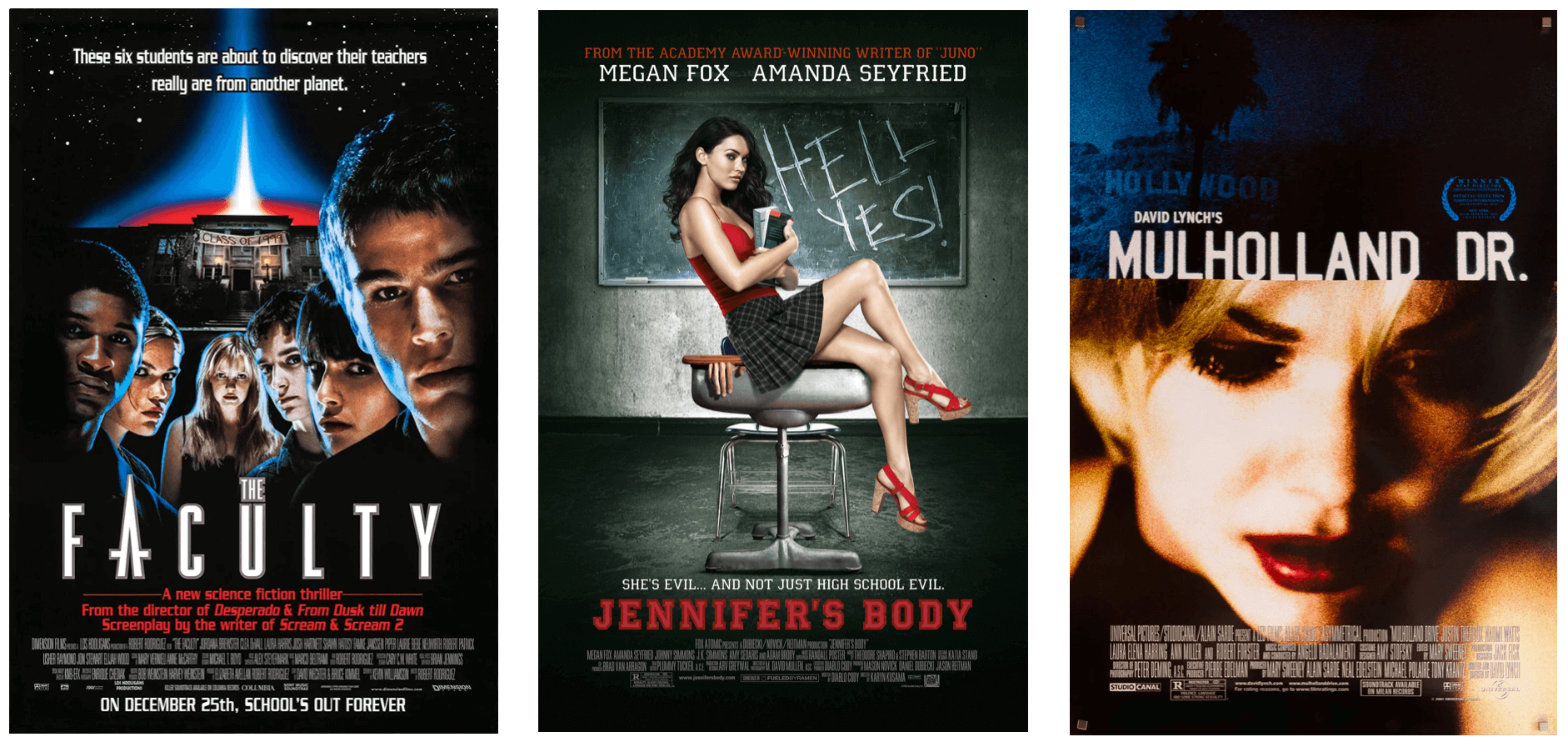

Howard Berger is a special make-up effects artist with over 800 feature film and television credits, including Aliens, Misery, Casino, Scream, Boogie Nights, Kill Bill, and Mulholland Drive.

In 2006 Howard won the Academy Award for Best Make-Up as well as a British Academy Award for Best Achievement in Make-Up for The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. He is currently on the Board of Governors for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

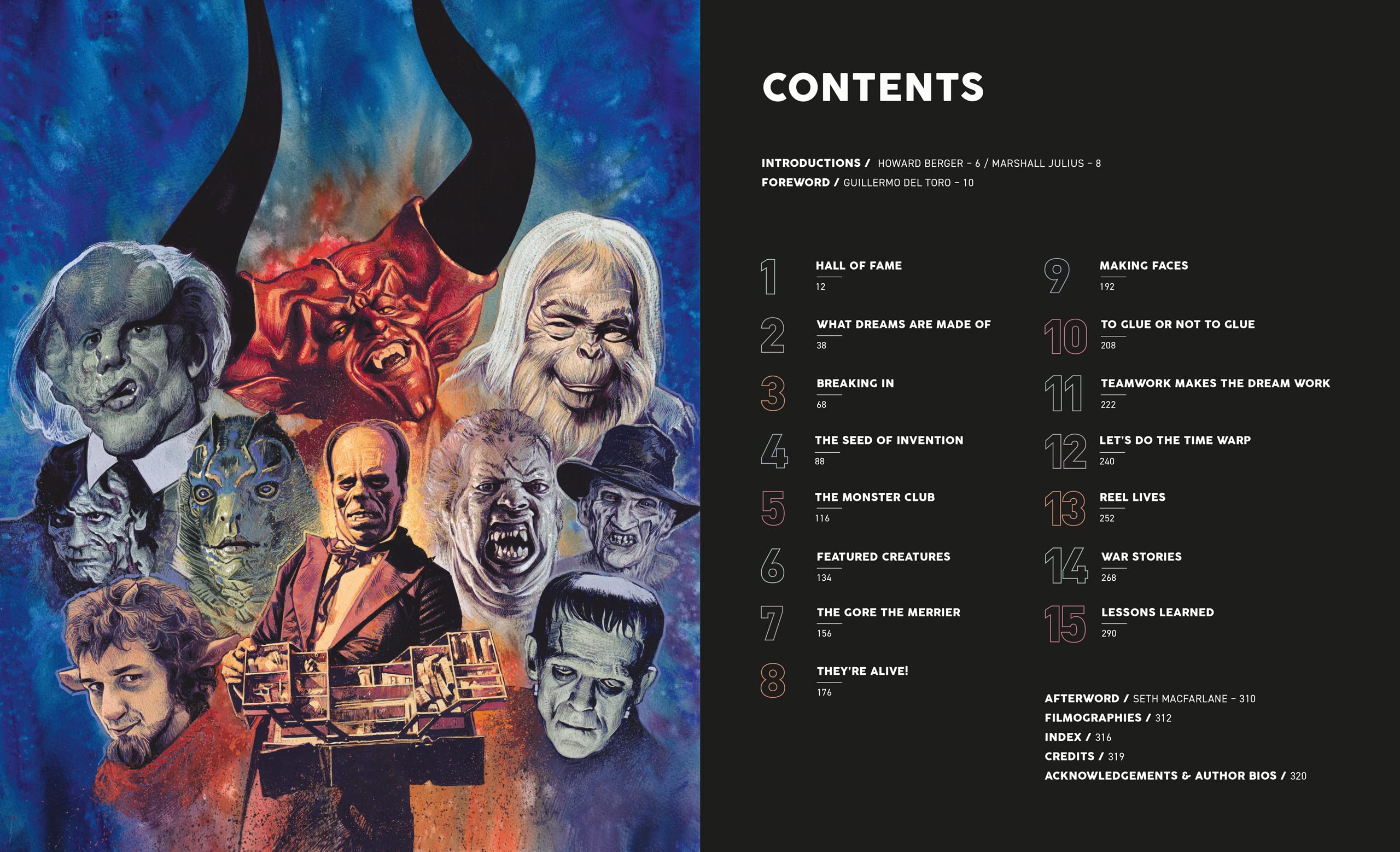

His new book, Masters of Make-Up Effects: A Century of Practical Magic, co-authored with Marshall Julius, with a foreward by Guillermo del Toro, is described as “the most complete book on movie make-up history ever assembled.”

In the following interview, Howard gets into the history of movie make-up, talks about his formative experiences learning from Stan Winston, Dick Smith, and Rick Baker, and shares fascinating stories about his collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, Tim Burton, David Lynch, and more!

In 2006 Howard won the Academy Award for Best Make-Up as well as a British Academy Award for Best Achievement in Make-Up for The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. He is currently on the Board of Governors for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

His new book, Masters of Make-Up Effects: A Century of Practical Magic, co-authored with Marshall Julius, with a foreward by Guillermo del Toro, is described as “the most complete book on movie make-up history ever assembled.”

In the following interview, Howard gets into the history of movie make-up, talks about his formative experiences learning from Stan Winston, Dick Smith, and Rick Baker, and shares fascinating stories about his collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, Tim Burton, David Lynch, and more!

Jonathan Thomas: Your new book includes a nice passage by make-up artist Mike Marino, who worked on Black Swan, Coming 2 America, and The Batman. “What we do is so unique,” he says. “But we’re not just sculpting something to go sit in a gallery somewhere — we’re making functional, moving, engineered sculptures.” “We’re less credible than fine artists,” he adds, “as we’re generally thought of as technicians. Yet we’ve created an entirely new art form combining sculpture, painting, and movement. And beyond that, it’s functional. Then, at the end of the day, we rip it off and throw it out.”

Howard Berger: Mike Marino is a super-smart dude, and a hell of a make-up artist. I mean this is a guy who goes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art with some clay and just reproduces sculptures he’s looking at. It’s pretty spectacular. But it’s true. I get annoyed when people say, “You guys are technicians.” We’re not technicians, we’re artists.

I also don’t like the word “craft,” like when people say “You’re craft.” There’s a great production designer, Wynn Thomas, who’s production designed Spike Lee’s movies since the beginning. Wynn uses the word “discipline,” and I really like that word. Our discipline. Craft sounds like you’re going to Michael’s craft store and put together some kind of hand-turkey decoration.

I think Mike’s quote is accurate. We design something, we create it, it comes to life for that day with the help of an actor, working together in partnership. And at the end of the day it’s disposable. It’s a disposable art. We peel it off, clean up the actor, and throw it in the trash.

There are so many times on a film where it will be a big makeup and I take it off and throw it in the trash, and people say, “Oh my god, what are you doing?” But it’s done for the day. I mean I do know make-up artists who save everything — after they remove it they put it in a bag and store it — but it’s all just going to be garbage eventually, so I don’t know why they’re holding on to it. Ultimately, what ends up on film is the record. The record of the piece, the make-up, the art, will be on film or digital for the rest of its life.

And it’s always evolving, too. I never do a make-up the same way. I always change it. I do that so that it’s interesting to me, but also, through the course of doing a make-up for many days, I’ll find something that I think works better.

What about continuity?

I just change it enough. I finesse it. I remember talking to Rick Baker about this, and he said the same thing. He said “I never do the make-up the same way.” I mean I have the same process to some degree. It’s not like, “Oh my god, there are two make-ups.” It’s all in continuity, it has to be, but I might approach it a little differently, especially when you do a make-up sixty times. You gotta keep it interesting because after a while it’s like you never want to do this make-up again.

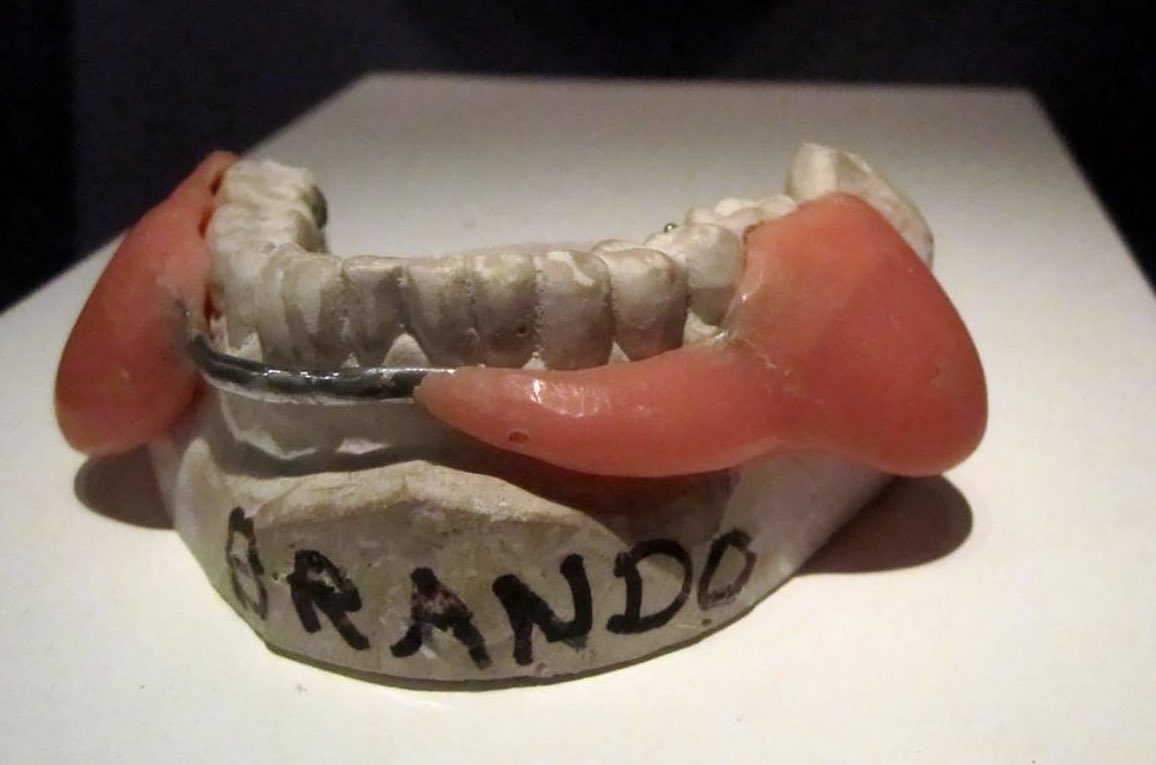

What you say about throwing your work away is interesting. The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is currently exhibiting the prosthetic nose piece worn by Danny DeVito when he performed the role of The Penguin in Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992). That was fun to see, so I guess I’m wondering how to think about this from the standpoint of exhibition. I take your point about the film being the record of the art, but I wonder: are make-ups something that can be displayed in the context of exhibition, or what are the challenges that exist in this kind of setting?

![Batman Returns (Tim Burton, 1992). Make-up design by Stan Winston Studios. Applied by Ve Neill.]()

That Danny DeVito piece was made at Stan Winston Studios. That’s from a run that wasn’t used. You can’t save anything once you’ve applied it. The removal process destroys the make-up. The removers you use eat it away at the material, it crumbles, and besides, you just want to get the actor out of the make-up because they have a turnaround and have to get home. Here at KNB we’ve donated quite a bit of stuff to the Academy, for preservation. There are a few little things that I personally have donated that have been on display. But yeah, it’s about maintaining history, and that’s one of the great things about the Academy Museum, and the Margaret Herrick Library — the preservation. I just handed over a ton of stuff to the Library, and I know it will always be there.

Did you give them anything that may be of interest to future researchers?

I gave them a billion scripts, 35 years of scripts, and storyboards for movies. Tons of photos. My production books. The Herrick Library is an amazing source for research. I was blown away.

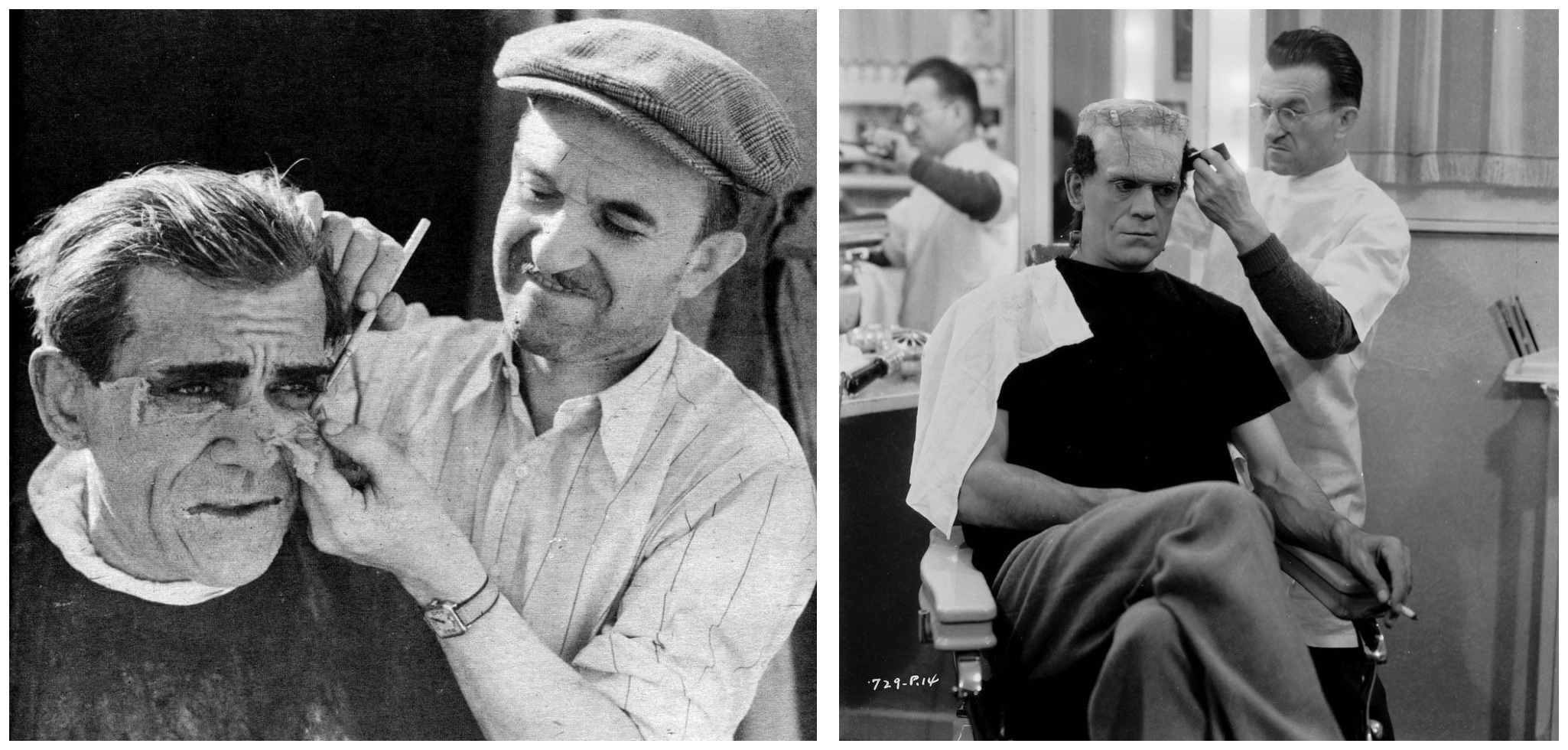

Most accounts of the history of movie make-up begin with Lon Chaney, the “Man of a Thousand Faces,” and then move on to Jack Pierce’s work, first at Fox with his simian make-up for The Monkey Talks (1927), followed by his work on the legendary Universal monsters of the 1930s and 40s. One thing I just read this morning is that Jack Pierce was fired from Universal in 1946, when he was 57 years old, ostensibly because he refused to adapt to new make-up techniques, which seems unbelievable given who we’re talking about.

Howard Berger: Mike Marino is a super-smart dude, and a hell of a make-up artist. I mean this is a guy who goes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art with some clay and just reproduces sculptures he’s looking at. It’s pretty spectacular. But it’s true. I get annoyed when people say, “You guys are technicians.” We’re not technicians, we’re artists.

I also don’t like the word “craft,” like when people say “You’re craft.” There’s a great production designer, Wynn Thomas, who’s production designed Spike Lee’s movies since the beginning. Wynn uses the word “discipline,” and I really like that word. Our discipline. Craft sounds like you’re going to Michael’s craft store and put together some kind of hand-turkey decoration.

I think Mike’s quote is accurate. We design something, we create it, it comes to life for that day with the help of an actor, working together in partnership. And at the end of the day it’s disposable. It’s a disposable art. We peel it off, clean up the actor, and throw it in the trash.

There are so many times on a film where it will be a big makeup and I take it off and throw it in the trash, and people say, “Oh my god, what are you doing?” But it’s done for the day. I mean I do know make-up artists who save everything — after they remove it they put it in a bag and store it — but it’s all just going to be garbage eventually, so I don’t know why they’re holding on to it. Ultimately, what ends up on film is the record. The record of the piece, the make-up, the art, will be on film or digital for the rest of its life.

And it’s always evolving, too. I never do a make-up the same way. I always change it. I do that so that it’s interesting to me, but also, through the course of doing a make-up for many days, I’ll find something that I think works better.

What about continuity?

I just change it enough. I finesse it. I remember talking to Rick Baker about this, and he said the same thing. He said “I never do the make-up the same way.” I mean I have the same process to some degree. It’s not like, “Oh my god, there are two make-ups.” It’s all in continuity, it has to be, but I might approach it a little differently, especially when you do a make-up sixty times. You gotta keep it interesting because after a while it’s like you never want to do this make-up again.

What you say about throwing your work away is interesting. The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is currently exhibiting the prosthetic nose piece worn by Danny DeVito when he performed the role of The Penguin in Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992). That was fun to see, so I guess I’m wondering how to think about this from the standpoint of exhibition. I take your point about the film being the record of the art, but I wonder: are make-ups something that can be displayed in the context of exhibition, or what are the challenges that exist in this kind of setting?

Did you give them anything that may be of interest to future researchers?

I gave them a billion scripts, 35 years of scripts, and storyboards for movies. Tons of photos. My production books. The Herrick Library is an amazing source for research. I was blown away.

Most accounts of the history of movie make-up begin with Lon Chaney, the “Man of a Thousand Faces,” and then move on to Jack Pierce’s work, first at Fox with his simian make-up for The Monkey Talks (1927), followed by his work on the legendary Universal monsters of the 1930s and 40s. One thing I just read this morning is that Jack Pierce was fired from Universal in 1946, when he was 57 years old, ostensibly because he refused to adapt to new make-up techniques, which seems unbelievable given who we’re talking about.

It was pretty unceremonious from what I understand. That was the time of the Westmores, so Bud Westmore was put into play in Jack Pierce’s position. The Westmores of Hollywood. All the brothers were stationed at different studios. What they did to Jack Pierce was a terrible thing. Here’s a guy who created the most iconic make-up ever. I think the most iconic make-up ever is Frankenstein’s Monster. Because you can look at a silhouette and go, “Oh, that’s Frankenstein’s Monster.” It is the most iconic make-up of all time, and it was beautiful. Everything Jack Pierce did at Universal was beautiful, and perfect, and amazing. Even if he wouldn’t bend about something, I think the way Universal dealt with him was pretty heartless.

There’s a Rick Baker video interview describing how make-up appliances work, where he talks about how Jack Pierce’s make-ups were fabricated afresh day after day, which was incredibly labor intensive and took hours. 8 hours on Frankenstein’s Monster, 10 hours on the Mummy. Do you think the studio was concerned with time?

It’s possible. But you also have to remember there was The Wizard of Oz, which was a major turning point given the foam rubber technology they designed and created for that.

![Character make-ups designed by Jack Dawn for The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939)]()

They knew they had to do these make-ups every single day and create continuity, so it wasn’t going to be a construction make-up. Jack Pierce was about constructing out-of-the-kit make-ups. They were great and beautiful, but it would be difficult to produce them over & over & over again, and very time consuming. I do know that Jack Pierce ended up doing a foam rubber Wolfman nose and muzzle, which I heard about and saw a photo of it. Maybe he didn’t want to bend to new techniqes. But as long as what Jack Pierce was doing was great, I would have just let him do it his way, you know? Ultimately I always say there’s a hundred ways to make a hamburger, but at the end of the day, it’s a hamburger.

Do you have a favorite hamburger in LA?

My favorite hamburger in LA? Oh, well that’s tough. I actually like this place called Burger Lounge. It’s really good, and they’re all over the place, but there’s one by my house in Sherman Oaks, and it’s a killer burger. But yeah, the burgers have to be really specific. The trick is, the bun has to be sturdy and grilled, or else the juice just melts it and you have a gooey mess. Stout has pretty good burgers, except they could grill their buns a little bit more. There’s a place called Laurel Tavern which has pretty good burgers, but they could grill their buns… It’s about the grilling of the bun, so it doesn’t fall apart on you.

So we kind of know about make-up artists like Lon Chaney and Jack Pierce, John Chambers, Dick Smith. Are there any make-up artists who you find are maybe left out of the canonical historical account?

Yeah, absolutely. Cecil Holland was really the first. It was him and Lon Chaney kind of neck-in-neck. Cecil Holland was a studio make-up department head and did a lot of work in the early days. You also had, in the U.K., people like Stuart Freeborn, and Roy Ashton, and Christopher Tucker, although he came a little bit later.

But yeah you had that whole other thing going on in the U.K. as well, with all the Hammer horror films. That was all Roy Ashton, and I love all that stuff, especially the Oliver Reed werewolf in Curse of the Werewolf, although that movie is horrible. It’s the slowest movie in the world, but it’s got a really great werewolf.

I was lucky enough to work with Oliver Reed years & years ago and I asked him about it. I was like, “Would you mind talking about The Curse of the Werewolf?” And he said it was his most favorite film he ever worked on, because he got to play a werewolf, and he was in full make-up, and it was really really fun. And he said, “You know, people never ask me about that.”

So it’s always fun to do that, to ask actors. They don’t expect it. I remember when I was working on Kill Bill and I was with Darryl Hannah, and I said “Darryl, can I ask you a question?” And she got a little annoyed, because she thought I was going to ask her something like, “What was it like dating JFK?” But I was like, “What did they use to glue that tail down on Splash?” And then she just smiled and went, “Oh, they super-glued it to me, and I still have scars.” And I said, “They super-glued it??” And she said “Yeah, it was some sort of urethane of something and they super-glued it because of the water.” I was like, “That’s crazy.” And then she was like, “Look here, these are the scars still on my stomach from Splash.” From peeling it off and taking her skin. But yeah, that was funny. She thought I was going to ask her about JFK or something, and I was like, no, I want to know about your mermaid tail!

What are your thoughts on the gendered division of labor in Hollywood history? You can see how, in cinematography for example, it was always men, cameramen, maybe going back to the physical labor of cranking. Whereas women — who played many roles in moviemaking before the corporatization of the studio system — were often employed as editors, perhaps given the associations of handiwork, knitting, and textiles. It’s sort of interesting — it seems like movie make-up would be a field that more women would have moved into, historically, but it wasn’t. Any thoughts on why?

It was a male-dominated industry, but it’s not that way now. I’m going to say there are more women than men in the make-up world. I do a lot of talking at make-up schools. For the book signing stuff I went to two schools, one was Cinema Make-up. There were 120 students there, and I would say 96% were female. And I asked the guy who runs it, “What’s the ratio?” and he said it’s about 90% women.

What do you think accounts for that shift?

I don’t know, it’s crazy. I mean there are a lot of women who love monsters and they love make-up. But I think the thing is, with school, students go for many reasons. They don’t just go to become monster makers. They also go to be able to get a job at MAC or work for another line, and that’s a specialty make-up in itself.

We have quite a number of women who work here at KNB. I’m going to say almost half the crew is female. It’s great. It’s a different take on things. And I love working with women when I’m on set. My crews are majority female. Tami Lane, who I’ve worked with forever, for the last 28 years, is great. It’s not like I have some sort of initiative, like you must hire women. I just like working with women. Erica Preus, a great make-up artist, was my co-Department Head on the project I just worked on, The Santa Clauses, which will be on Disney Plus. That was our first time working as co’s and it was great. Erica is a mom as well so she was able to juggle her personal life with her professional life. She’s really quite amazing, and can do anything, a triple-threat, and I love it. It’s about elevating people.

If you could hop in a time machine like the DeLorean or whathaveyou and go back in time to land in a particular make-up room, to observe how a particular make-up was applied, I mean a make-up you’ve always wondered about or admired from the standpoint of artistry, where would you go?

That’s easy. I’d go to Universal while they were shooting Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954).

![]()

![Above: make-up artist Milicent Patrick, designer of the Creature in The Creature from the Black Lagoon (Jack Arnold, 1954)]()

That’s my favorite creature suit. My favorite monster. I watch that movie all the time, and I think it holds up so beautifully. It’s perfect. I would have loved to have seen it, to see what color it really was. Touch it, see what it felt like. Watch it, see Ricou Browning get into it and go do his swimming stuff as the Creature. Or Ben Chapman do all the Creature stuff on land. Definitely, I would love love love to go back in time and be on the set of The Creature form the Black Lagoon, and see all those guys working, and putting that suit together, to see how it holds up, how that whole mechanism with the jaw opening and closing and the gills moving. I mean that was the 50s and they nailed it. There’s been talk, of course, about rebooting it, and I’m like, they better not. And if they do, they should just use the same exact design, because that design is perfect. It doesn't need to be redesigned. It doesn't need digital components. Just make it that guy in the suit. It’s beyond perfect.

When that movie was released in 1954, the category of “special make-up effects” didn’t exist; it didn’t emerge until a couple decades later. In the documentary Making Apes: The Artists Who Changed Film (2019), Tom Burman claims to have coined the term, adding that the union didn’t like it, John Chambers didn’t like it, and Stan Winston was the only one to back him up. What is there not to like about this term? Or what were the stakes of this debate?

You know, that was a little before my days, but I do remember hearing about special make-up effects and Rick Baker. I think there was a discussion about, is it “make-up special effects,” or is it “special effects make-up.” I say “special make-up effects,” because “make-up special effects” doesn’t make sense to me. Even today the union, Local 706, does not have a category for special make-up, or prosthetic make-up artists. There is a category that says “make-up tech,” and that was established who knows when, when there were union make-up people working at the studios in the staff shops, not on set, but prepping and building creatures and make-ups or what have you, working on the studio lot within the make-up department, and they were considered techs.

So that terminology continues today. A make-up tech is basically a special make-up effects artist, or a prosthetic make-up artist. I hate it with a passion, plus it confuses production continually. So I put in a request to change the name. We’re not techs, and I think it’s utterly insulting. It should be prosthetic make-up artists, because that’s what we are. We go to set and do prosthetics. We’re not teching anything. We’re make-up artists. It’s a really contradictory term, because we make it a point in Local 706 to state “make-up artists,” but then why is there “make-up tech”? Why are we called techs? But yeah, hopefully we can change it. It has to go to a vote, yada yada yada. It would be nice. There are so many make-up effects artists, and make-up effects artists really brought make-up to a light. The reason they have all these schools and there are people are so obsessed is because we have make-up effects. I truly believe that. It’s not like people are like, “Oh wow, that eyeliner is so amazing. I want to be a make-up artist when I grow up.” It was people like Rick Baker, and Stan Winston, and Tom Burman, Rob Bottin, and all those guys. They were the leaders. I was a total Dick Smith, Rick Baker, Stan Winston fanatic. Those were my three. They are the holy trinity to me.

There’s a Rick Baker video interview describing how make-up appliances work, where he talks about how Jack Pierce’s make-ups were fabricated afresh day after day, which was incredibly labor intensive and took hours. 8 hours on Frankenstein’s Monster, 10 hours on the Mummy. Do you think the studio was concerned with time?

It’s possible. But you also have to remember there was The Wizard of Oz, which was a major turning point given the foam rubber technology they designed and created for that.

They knew they had to do these make-ups every single day and create continuity, so it wasn’t going to be a construction make-up. Jack Pierce was about constructing out-of-the-kit make-ups. They were great and beautiful, but it would be difficult to produce them over & over & over again, and very time consuming. I do know that Jack Pierce ended up doing a foam rubber Wolfman nose and muzzle, which I heard about and saw a photo of it. Maybe he didn’t want to bend to new techniqes. But as long as what Jack Pierce was doing was great, I would have just let him do it his way, you know? Ultimately I always say there’s a hundred ways to make a hamburger, but at the end of the day, it’s a hamburger.

Do you have a favorite hamburger in LA?

My favorite hamburger in LA? Oh, well that’s tough. I actually like this place called Burger Lounge. It’s really good, and they’re all over the place, but there’s one by my house in Sherman Oaks, and it’s a killer burger. But yeah, the burgers have to be really specific. The trick is, the bun has to be sturdy and grilled, or else the juice just melts it and you have a gooey mess. Stout has pretty good burgers, except they could grill their buns a little bit more. There’s a place called Laurel Tavern which has pretty good burgers, but they could grill their buns… It’s about the grilling of the bun, so it doesn’t fall apart on you.

So we kind of know about make-up artists like Lon Chaney and Jack Pierce, John Chambers, Dick Smith. Are there any make-up artists who you find are maybe left out of the canonical historical account?

Yeah, absolutely. Cecil Holland was really the first. It was him and Lon Chaney kind of neck-in-neck. Cecil Holland was a studio make-up department head and did a lot of work in the early days. You also had, in the U.K., people like Stuart Freeborn, and Roy Ashton, and Christopher Tucker, although he came a little bit later.

But yeah you had that whole other thing going on in the U.K. as well, with all the Hammer horror films. That was all Roy Ashton, and I love all that stuff, especially the Oliver Reed werewolf in Curse of the Werewolf, although that movie is horrible. It’s the slowest movie in the world, but it’s got a really great werewolf.

I was lucky enough to work with Oliver Reed years & years ago and I asked him about it. I was like, “Would you mind talking about The Curse of the Werewolf?” And he said it was his most favorite film he ever worked on, because he got to play a werewolf, and he was in full make-up, and it was really really fun. And he said, “You know, people never ask me about that.”

So it’s always fun to do that, to ask actors. They don’t expect it. I remember when I was working on Kill Bill and I was with Darryl Hannah, and I said “Darryl, can I ask you a question?” And she got a little annoyed, because she thought I was going to ask her something like, “What was it like dating JFK?” But I was like, “What did they use to glue that tail down on Splash?” And then she just smiled and went, “Oh, they super-glued it to me, and I still have scars.” And I said, “They super-glued it??” And she said “Yeah, it was some sort of urethane of something and they super-glued it because of the water.” I was like, “That’s crazy.” And then she was like, “Look here, these are the scars still on my stomach from Splash.” From peeling it off and taking her skin. But yeah, that was funny. She thought I was going to ask her about JFK or something, and I was like, no, I want to know about your mermaid tail!

It was a male-dominated industry, but it’s not that way now. I’m going to say there are more women than men in the make-up world. I do a lot of talking at make-up schools. For the book signing stuff I went to two schools, one was Cinema Make-up. There were 120 students there, and I would say 96% were female. And I asked the guy who runs it, “What’s the ratio?” and he said it’s about 90% women.

What do you think accounts for that shift?

I don’t know, it’s crazy. I mean there are a lot of women who love monsters and they love make-up. But I think the thing is, with school, students go for many reasons. They don’t just go to become monster makers. They also go to be able to get a job at MAC or work for another line, and that’s a specialty make-up in itself.

We have quite a number of women who work here at KNB. I’m going to say almost half the crew is female. It’s great. It’s a different take on things. And I love working with women when I’m on set. My crews are majority female. Tami Lane, who I’ve worked with forever, for the last 28 years, is great. It’s not like I have some sort of initiative, like you must hire women. I just like working with women. Erica Preus, a great make-up artist, was my co-Department Head on the project I just worked on, The Santa Clauses, which will be on Disney Plus. That was our first time working as co’s and it was great. Erica is a mom as well so she was able to juggle her personal life with her professional life. She’s really quite amazing, and can do anything, a triple-threat, and I love it. It’s about elevating people.

If you could hop in a time machine like the DeLorean or whathaveyou and go back in time to land in a particular make-up room, to observe how a particular make-up was applied, I mean a make-up you’ve always wondered about or admired from the standpoint of artistry, where would you go?

That’s easy. I’d go to Universal while they were shooting Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954).

That’s my favorite creature suit. My favorite monster. I watch that movie all the time, and I think it holds up so beautifully. It’s perfect. I would have loved to have seen it, to see what color it really was. Touch it, see what it felt like. Watch it, see Ricou Browning get into it and go do his swimming stuff as the Creature. Or Ben Chapman do all the Creature stuff on land. Definitely, I would love love love to go back in time and be on the set of The Creature form the Black Lagoon, and see all those guys working, and putting that suit together, to see how it holds up, how that whole mechanism with the jaw opening and closing and the gills moving. I mean that was the 50s and they nailed it. There’s been talk, of course, about rebooting it, and I’m like, they better not. And if they do, they should just use the same exact design, because that design is perfect. It doesn't need to be redesigned. It doesn't need digital components. Just make it that guy in the suit. It’s beyond perfect.

When that movie was released in 1954, the category of “special make-up effects” didn’t exist; it didn’t emerge until a couple decades later. In the documentary Making Apes: The Artists Who Changed Film (2019), Tom Burman claims to have coined the term, adding that the union didn’t like it, John Chambers didn’t like it, and Stan Winston was the only one to back him up. What is there not to like about this term? Or what were the stakes of this debate?

You know, that was a little before my days, but I do remember hearing about special make-up effects and Rick Baker. I think there was a discussion about, is it “make-up special effects,” or is it “special effects make-up.” I say “special make-up effects,” because “make-up special effects” doesn’t make sense to me. Even today the union, Local 706, does not have a category for special make-up, or prosthetic make-up artists. There is a category that says “make-up tech,” and that was established who knows when, when there were union make-up people working at the studios in the staff shops, not on set, but prepping and building creatures and make-ups or what have you, working on the studio lot within the make-up department, and they were considered techs.

So that terminology continues today. A make-up tech is basically a special make-up effects artist, or a prosthetic make-up artist. I hate it with a passion, plus it confuses production continually. So I put in a request to change the name. We’re not techs, and I think it’s utterly insulting. It should be prosthetic make-up artists, because that’s what we are. We go to set and do prosthetics. We’re not teching anything. We’re make-up artists. It’s a really contradictory term, because we make it a point in Local 706 to state “make-up artists,” but then why is there “make-up tech”? Why are we called techs? But yeah, hopefully we can change it. It has to go to a vote, yada yada yada. It would be nice. There are so many make-up effects artists, and make-up effects artists really brought make-up to a light. The reason they have all these schools and there are people are so obsessed is because we have make-up effects. I truly believe that. It’s not like people are like, “Oh wow, that eyeliner is so amazing. I want to be a make-up artist when I grow up.” It was people like Rick Baker, and Stan Winston, and Tom Burman, Rob Bottin, and all those guys. They were the leaders. I was a total Dick Smith, Rick Baker, Stan Winston fanatic. Those were my three. They are the holy trinity to me.

In the “Introduction” you wrote for your new book, you begin by zooming in on gorillas — first 1972’s The Thing With Two Heads, which featured a two-headed gorilla designed by Rick Baker, who was 22 years old at the time. A paragraph later you say that your all-time favorite gorilla is the one Baker designed for 1981’s The Incredible Shrinking Woman, starring Lilly Tomlin. Not only did Baker design that gorilla, he performed it! What makes this your favorite simian makeup? Or what details are you observing when making this sort of assessment?

Well I love Sidney. I think it’s a really fun character. Why I love it is because I know Rick Baker’s in it. But there’s something about the look of Sidney. I like the color of his hair. There’s a lot of red going on. I love the sculpture. I’m hoping that one day Rick will actually hear what I’m saying and just give me a pull out of the mold, and go here’s the Sidney head — here it is. I’d have a heart attack. There’s just a quality to that gorilla. I don’t love the movie, but I’ve watched it a million times, because Rick Baker. I just think Rick brought it to life. His movements are great. He’s such a great performer in that suit. It’s a beautiful suit. And it feels real, it feels alive. And I just love gorillas anyhow. That obviously stems back to Planet of the Apes, because I was a massive Planet of the Apes fan, and still am. Anything simian I just love. Even the Dino de Laurentis King Kong. I love it, I know people hate it. But I just love the Rick Baker stuff.

So if you were to travel to outer space and could only take two Rick Baker movies with you, to show extraterrestrials the best of his work, or two of your personal faves, which two would you bring?

That’s hard, but okay. I would bring Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), because I think that’s a cool movie and I love all the apes Rick did in it.

Well I love Sidney. I think it’s a really fun character. Why I love it is because I know Rick Baker’s in it. But there’s something about the look of Sidney. I like the color of his hair. There’s a lot of red going on. I love the sculpture. I’m hoping that one day Rick will actually hear what I’m saying and just give me a pull out of the mold, and go here’s the Sidney head — here it is. I’d have a heart attack. There’s just a quality to that gorilla. I don’t love the movie, but I’ve watched it a million times, because Rick Baker. I just think Rick brought it to life. His movements are great. He’s such a great performer in that suit. It’s a beautiful suit. And it feels real, it feels alive. And I just love gorillas anyhow. That obviously stems back to Planet of the Apes, because I was a massive Planet of the Apes fan, and still am. Anything simian I just love. Even the Dino de Laurentis King Kong. I love it, I know people hate it. But I just love the Rick Baker stuff.

So if you were to travel to outer space and could only take two Rick Baker movies with you, to show extraterrestrials the best of his work, or two of your personal faves, which two would you bring?

That’s hard, but okay. I would bring Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), because I think that’s a cool movie and I love all the apes Rick did in it.

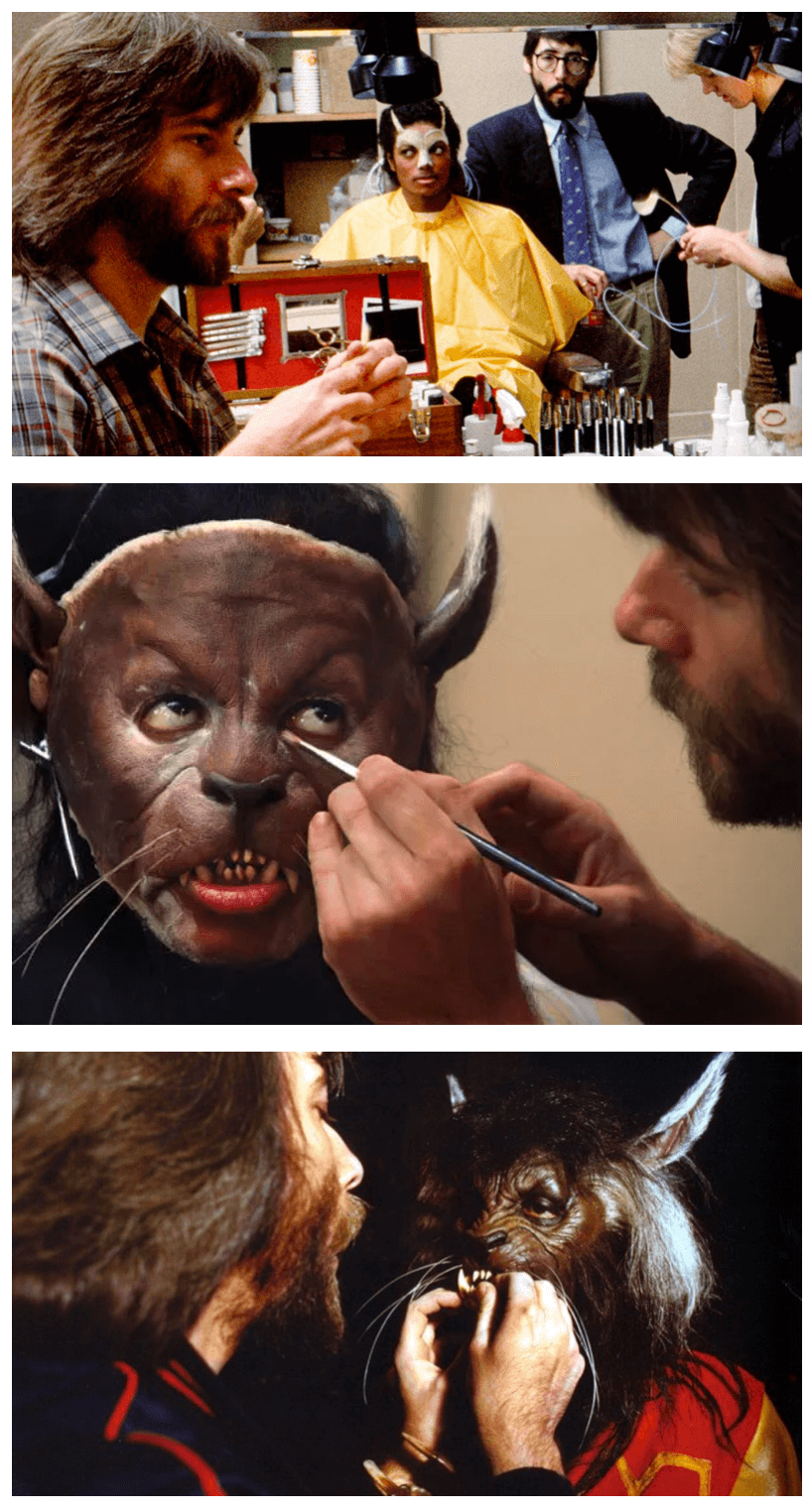

And then, well I’m going to have to say it’s a tie, between American Werewolf in London, which I love, and Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which we were talking about earlier. Because Thriller was the first time I really saw behind-the-scenes. I love the music video, the short film by John Landis, but I love Making Michael Jackson’s Thriller. MTV ran the living shit out of it. It was on 24/7 for like a month, and I would watch the making of Thriller over and over. Just a video of Rick Baker taking his make-up off and talking was so magical. And I’m like, “Look at how great that is!” Seeing how he does the make-up, how he does this, how he does that. At that point I was already a Rick Baker fan. I was obsessed with Rick Baker.

![In 1982, Rick Baker won the first Oscar for Make-Up for his work on An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1981)]()

With American Werewolf, I just couldn’t believe my eyes. Aside from being a giant Rick Baker fan, I’m a giant John Landis fan. I love John Landis, I think he’s amazing, he makes great films, a smart guy, funny as hell, and I think An American Werewolf in London is really fantastic, so it’s a tie between those two, which are both Landis movies. Maybe if I took Thriller and it came with the Making of Thriller, then I would take them. I would say we’re going to watch this, and then we’re going to watch this, and I’m going to show you guys how great Rick Baker is.

![Rick Baker applying special make-ups to Michael Jackson for Michael Jackson's Thriller (John Landis, 1983)]()

![Rick Baker's special make-up design in Michael Jackson's Thriller (John Landis, 1983)]()

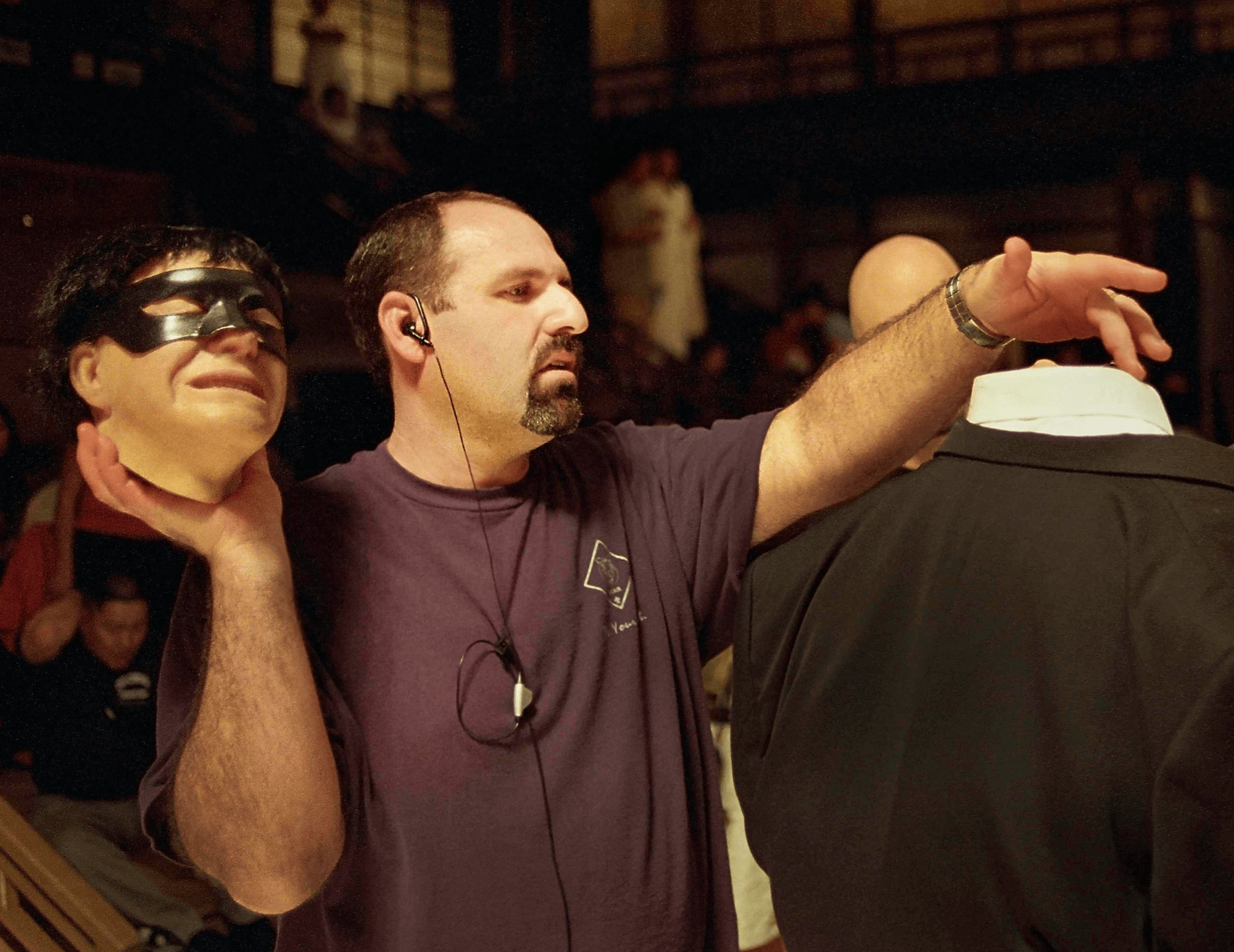

You mentioned Rick Baker performing the gorilla. In 2001, you had a chance to play a gorilla yourself, in Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes. What was that like? And once you were in character, what do you remember about Burton’s approach to directing your scenes?

[laughs] It’s at the beginning of the movie, when we’re on the Oberon, the ship, the first time we meet Mark Whalberg and everybody. And there are all these cages. And in the cage is a gorilla. Well honestly they couldn’t have real gorillas, but they had real chimps. There was a guy Bob Dunn, who used to handle apes for films, he brought his chimps. Some were pretty unruly. There was one above me whose name was Bella, who I knew as a little chimp, who came to my house and played with my kids. But Bella at that point was gigantic, monstrous, and pretty angry. Anyhow I had gotten a call, because I had worked with Tim Burton on Mars Attacks!

![Mars Attacks! (Tim Burton, 1996)]()

What did you do on Mars Attacks!?

All the make-up effects stuff. Tons of stuff on that. So I was probably talking to Tim about a gorilla suit one day, because I got a call from Tim’s office saying, “Hey Howard, Tim remembers you have a gorilla suit. Do you want to be a gorilla in a cage in Planet of the Apes?” And I said, “Are you kidding? Yes!” So I took my suit down there and made my eyes up and sat in the cage all day and did my thing. And I remember Mark Wahlberg walked past and he was like, “Man are you okay in there?” And I’m like, “Yeah yeah, I’m good.” And he’s like, “Is it hot in there?” And I went, “Yeah yeah, but it’s good.” And he was like, “Alright man, you be good.” So I was just a gorilla all day, and I would get my breaks and go outside and take the head off and walk around, and I felt like it was so old-Hollywood, being on a studio lot as a guy in a gorilla suit holding a gorilla head with big black eyes. I had friends who were working on the movie, too. It was just fun, it felt so Hollywood. I just needed a guy in a spacesuit, and a bunch of cowboys and Indians, and dancing girls, and it would be right out of some 40s and 50s behind the scenes film.

Years later, after I started working with Mark Whalberg as his personal make-up artist, I said, “Hey Mark, do you remember on Planet of the Apes there was a guy in a gorilla suit…” and he was like, “Yeah yeah yeah,” and I said, “That was me!” And he was like, “What the hell were you doing in a gorilla suit?” And I said, “Why not?” Any opportunity to be in a gorilla suit and I’m going to take it, especially if Tim Burton calls you saying, hey Howard, do you want to be in a gorilla suit for two days? So I said Oh my god, yes. Absolutely. So I was only in that sequence — I wasn’t in the beautiful make-ups Rick Baker did. But yeah, I did it, and I still get my SAG residuals for playing the gorilla. They’re miniscule, but it’s fun.

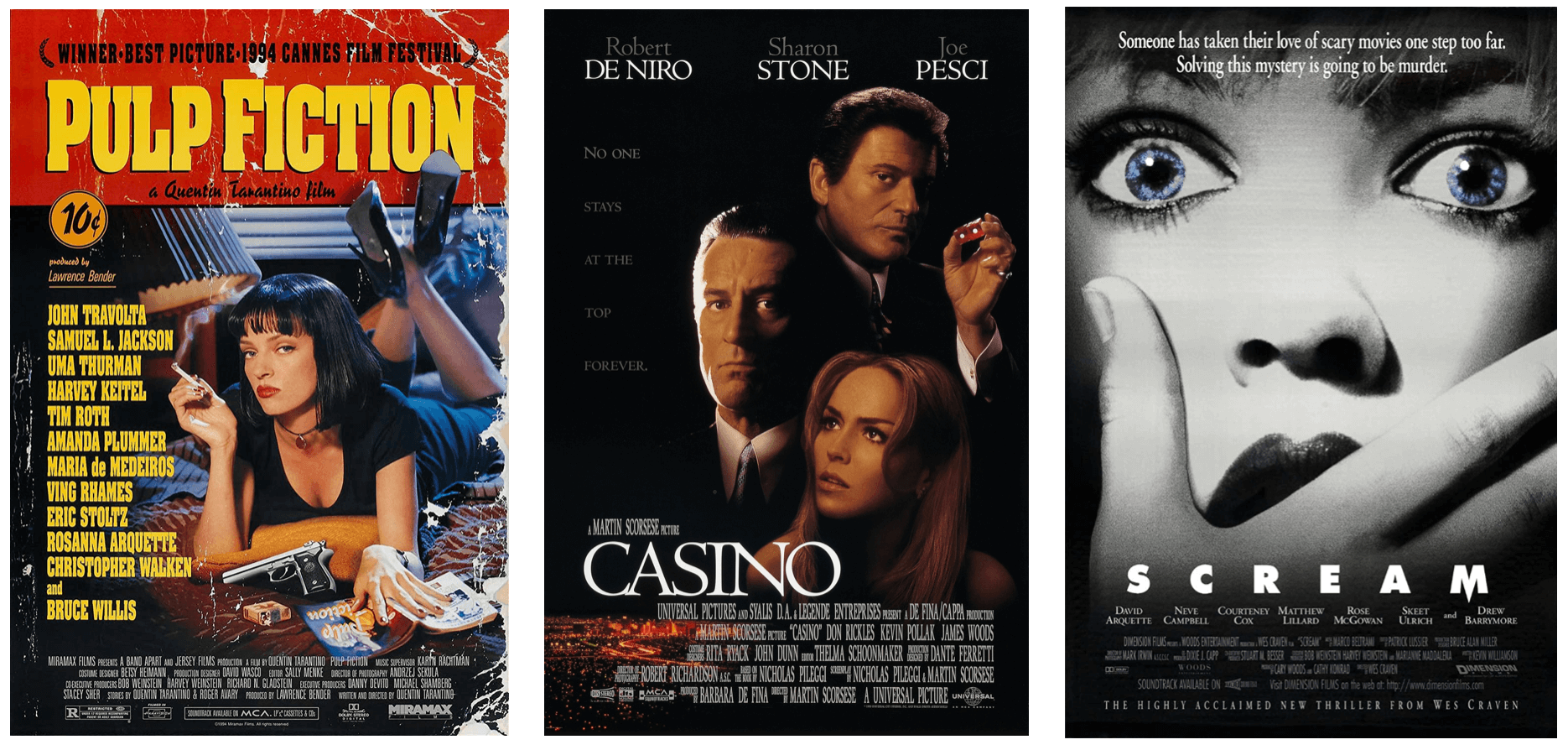

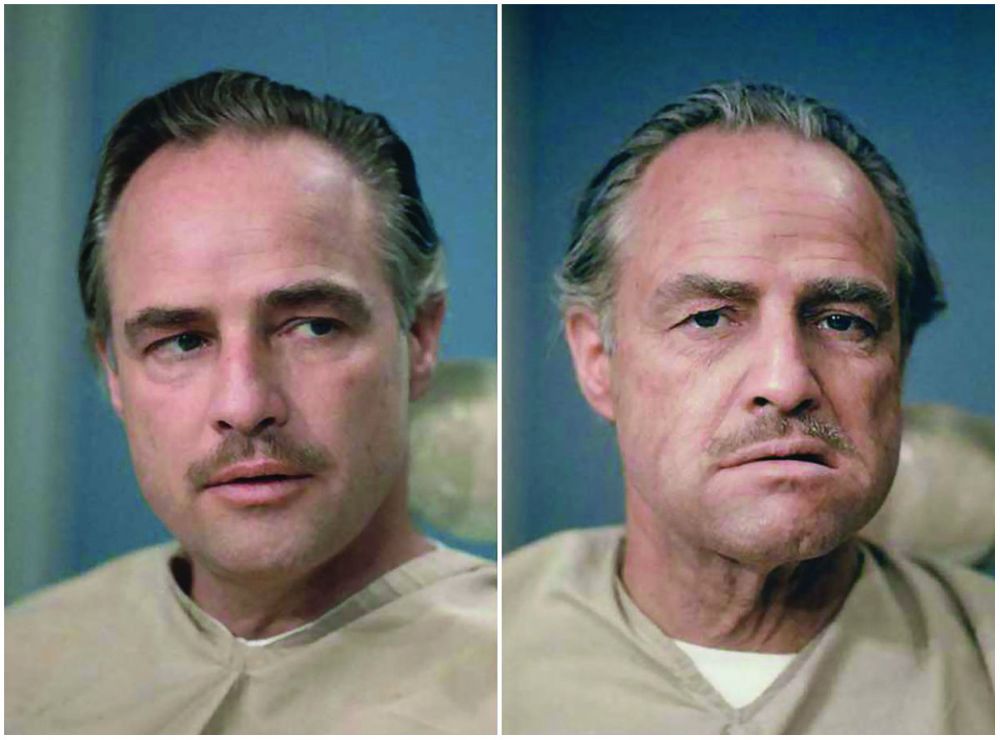

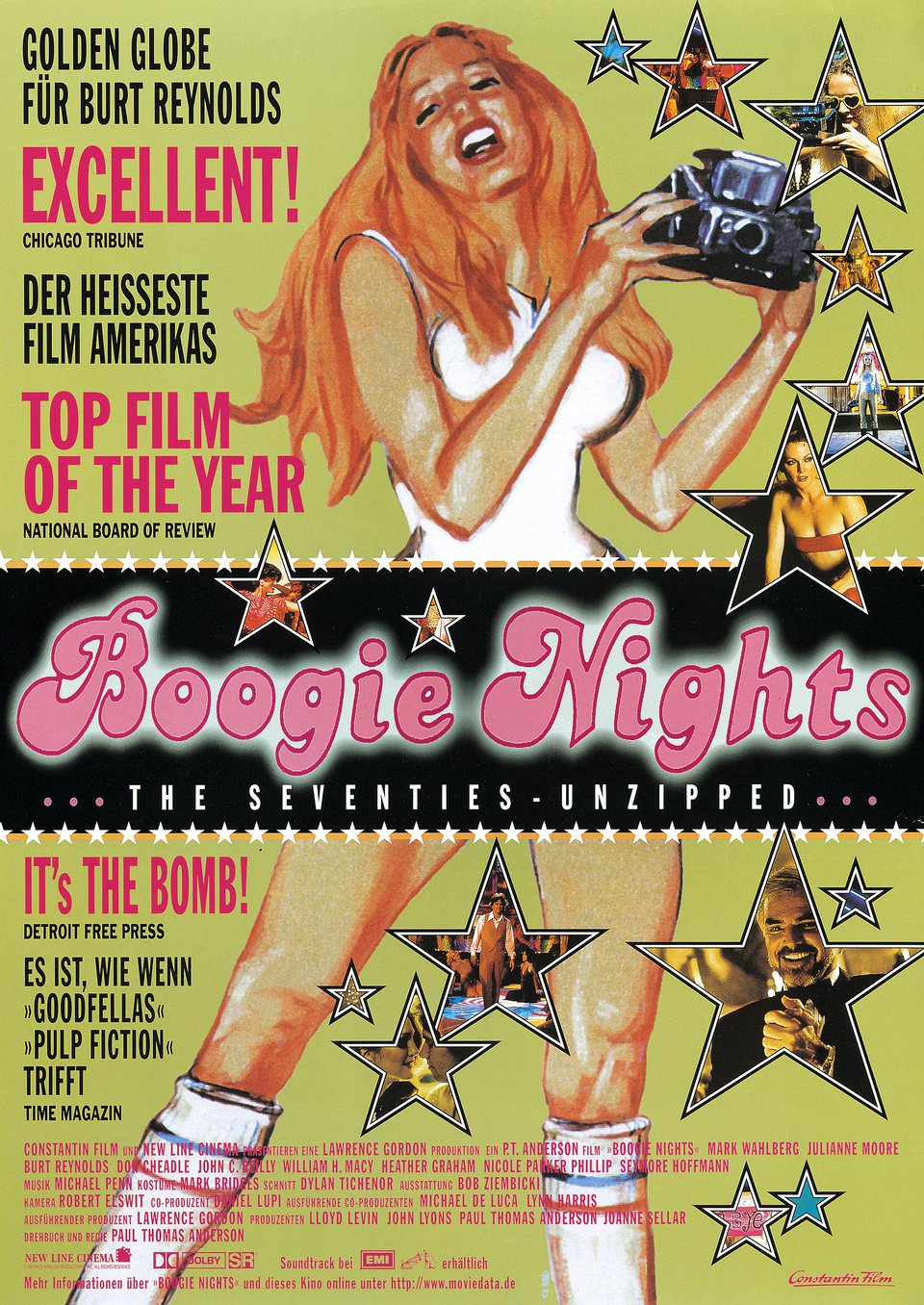

Since you mention Mark Whalberg, did you make the giant penis for Dirk Diggler, for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights?

With American Werewolf, I just couldn’t believe my eyes. Aside from being a giant Rick Baker fan, I’m a giant John Landis fan. I love John Landis, I think he’s amazing, he makes great films, a smart guy, funny as hell, and I think An American Werewolf in London is really fantastic, so it’s a tie between those two, which are both Landis movies. Maybe if I took Thriller and it came with the Making of Thriller, then I would take them. I would say we’re going to watch this, and then we’re going to watch this, and I’m going to show you guys how great Rick Baker is.

You mentioned Rick Baker performing the gorilla. In 2001, you had a chance to play a gorilla yourself, in Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes. What was that like? And once you were in character, what do you remember about Burton’s approach to directing your scenes?

[laughs] It’s at the beginning of the movie, when we’re on the Oberon, the ship, the first time we meet Mark Whalberg and everybody. And there are all these cages. And in the cage is a gorilla. Well honestly they couldn’t have real gorillas, but they had real chimps. There was a guy Bob Dunn, who used to handle apes for films, he brought his chimps. Some were pretty unruly. There was one above me whose name was Bella, who I knew as a little chimp, who came to my house and played with my kids. But Bella at that point was gigantic, monstrous, and pretty angry. Anyhow I had gotten a call, because I had worked with Tim Burton on Mars Attacks!

What did you do on Mars Attacks!?

All the make-up effects stuff. Tons of stuff on that. So I was probably talking to Tim about a gorilla suit one day, because I got a call from Tim’s office saying, “Hey Howard, Tim remembers you have a gorilla suit. Do you want to be a gorilla in a cage in Planet of the Apes?” And I said, “Are you kidding? Yes!” So I took my suit down there and made my eyes up and sat in the cage all day and did my thing. And I remember Mark Wahlberg walked past and he was like, “Man are you okay in there?” And I’m like, “Yeah yeah, I’m good.” And he’s like, “Is it hot in there?” And I went, “Yeah yeah, but it’s good.” And he was like, “Alright man, you be good.” So I was just a gorilla all day, and I would get my breaks and go outside and take the head off and walk around, and I felt like it was so old-Hollywood, being on a studio lot as a guy in a gorilla suit holding a gorilla head with big black eyes. I had friends who were working on the movie, too. It was just fun, it felt so Hollywood. I just needed a guy in a spacesuit, and a bunch of cowboys and Indians, and dancing girls, and it would be right out of some 40s and 50s behind the scenes film.

Years later, after I started working with Mark Whalberg as his personal make-up artist, I said, “Hey Mark, do you remember on Planet of the Apes there was a guy in a gorilla suit…” and he was like, “Yeah yeah yeah,” and I said, “That was me!” And he was like, “What the hell were you doing in a gorilla suit?” And I said, “Why not?” Any opportunity to be in a gorilla suit and I’m going to take it, especially if Tim Burton calls you saying, hey Howard, do you want to be in a gorilla suit for two days? So I said Oh my god, yes. Absolutely. So I was only in that sequence — I wasn’t in the beautiful make-ups Rick Baker did. But yeah, I did it, and I still get my SAG residuals for playing the gorilla. They’re miniscule, but it’s fun.

Since you mention Mark Whalberg, did you make the giant penis for Dirk Diggler, for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights?

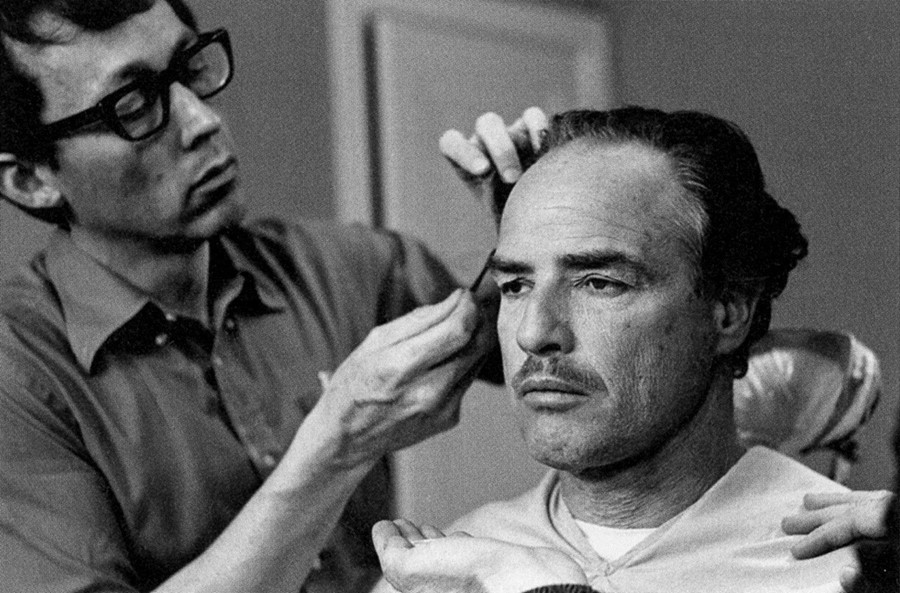

Mmm-hmm, yeah. We worked on Boogie. I knew Paul when we were kids, because my dad and Paul’s dad, Ernie Anderson, were very good friends and worked together all the time. My dad was a post-production sound editor and Ernie was the voice of ABC. So you’d hear Ernie all the time if you watched ABC, like “Next on The Love Boat...”, or “Next on Fantasy Island...” That was all Ernie, and my dad worked with Ernie everyday. So if I went to work with my dad on a Saturday, and if Ernie was working he would sometimes bring his son, Paul. And so Paul and I became friends. Not like we hung out all the time, but those times at the studio when we saw each other. And then all the sudden, when we’re older and professional, I got a call from Paul Thomas Anderson, and he’s like “Hey, it’s Paul,” and I’m like “Hey, what’s up?” And he says, “Well I’m doing this movie called Boogie Nights and I think I need your help.” And I’m like,“Okay.” So he says, “Come over to my office.” So I went down to Hollywood and went to his office and it was wall-to-wall porn. And I’m thinking to myself, I don’t know if I want to work on this movie? But he gave me the script and talked me through what he needed — there was other stuff in the movie, too.

Do you mean the scenes of violence?

Yeah yeah, and there was stuff that got cut out. Actually two big things that got cut out. When I read the script I was like, hmmmm, so I was happy when Paul cut it out. There’s a sequence with Alfred Molina, when he comes out all drugged-up.

![Alfred Molina in Boogie Nights (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1997)]()

That sequence continues to go on until the cops blow him away. So we did a full make-up on Alfred, with bullet hits and all that. Boom boom boom boom boom, with squibs, and then he dies. And if you remember, there was also talk of Johnny Wadd dying in a car accident in the movie. He’s the guy who replaces Mark Whalberg’s character, Dirk Diggler. That accident was with Dirk Diggler’s parents. And they’re dead at the scene and all that. And I just thought that was such a coincident thing, you know? We shot it all, but Paul cut both those scenes, and I thought that was awesome. I think it’s much better — but what the hell do I know: it’s Paul Thomas Anderson!

Anyhow, the big task was to make a large penis for Mark. Talking to Paul, he’s like “12 inches, man,” so we sculpt this 12-inch dick and all this stuff, and I do a test make-up with [KNB make-up artist] Garrett Immel and it’s way too big. Because Mark is actually like 5’7”, so it would look like it was 20-feet long. So I’m like, “Okay, we gotta redo this.” Garrett re-sculpted a 7-inch penis, which we tested on Mark, and that’s what we went with. So we had different versions, and actually in the movie we shot two scenes where you see it. One where he’s having sex with Amber Waves, Julianne Moore’s character, which got cut out, which is great, because Paul realized he was going to save it until the very end. We’ve been waiting the whole time to see what this is.

![Mark Whalberg in Boogie Nights (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1997)]()

Paul Thomas Anderson is quoted as saying “When we were shooting it I kept thinking, This is exactly like seeing the dinosaur in Jurassic Park or seeing the shark in Jaws…” In other words, you created a monster!

It is. We keep waiting and waiting. You keep getting a promise. You keep hearing about it, but you never see it. And then Paul brilliantly reveals it at the end in the way that he does. It’s great.

I remember talking to Mark — this is before he was married and all that — but he was like, “You know Howard, the thing is, the next girl I go out with is going to be really disappointed.” We ended up giving it to him. He has it in a glass box at home, in a safe.

He keeps it in a safe?

Yeah yeah, I went over at some point and said, “Do you still have it?” And he’s like, “Yeah, right here,” and he opened up the safe and there it is, in a glass box. And I’m like, “Yep, that’s it.” We gave him the one we made. But that was cool, and that was really masterminded by Garrett Immel, who’s a great artist I work with all the time. It’s not the first penis we’ve done, and it won’t be the last.

So besides performing as a gorilla in Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes, you performed as a zombie in George Romero’s Day of the Dead, and as a vampire in the Tarantino-Robert Rodriguez collaboration, From Dusk Till Dawn. Given this resume as an occasional actor, I was wondering what your experience was like acting as an ordinary human character for Paul Thomas Anderson in Licorice Pizza? Rumor has it you acted in some scenes?

It was wonderful. It was probably one of my most favorite times on set. I was disappointed when Paul called me and was like, “Dude, I cut your scene because the movie’s running too long.” But we shot one day. It was three scenes with Cooper, who plays the lead.

And you’re not wearing make-ups?

No, I’m not wearing make-ups, although it was during the pandemic, so Paul’s like, “Let your beard grow, and let your hair grow.” And it did. So I got bushy and did my own make-up and hair. And yeah, I played a real guy named Omar, who was the guy who Gary had manufacture the water beds. I think Paul had that scene where Gary first sees the waterbeds and thought it was redundant to go back and have another scene. It was all good. The thing is, I got to be on set with Paul Thomas Anderson as director.

And what was that like?

It was magnificent. It was so much fun to see his giddiness and how happy he is, and what worked and didn’t work. You know, change these lines, and drop this paragraph, and add this. And working with Cooper — it was just myself and Cooper in the scenes. I felt like I worked really really hard, I was tired at the end of the day, but I was exhilarated. But Paul lets you run with it. There were some things he was married to, word-wise, but sometimes, if there was a line I didn’t remember but was able to reconfigure to make it fluid, he was great with it. But yeah, he's very organic. On this movie he didn’t have an official cinematographer.

He sounds like a cinematographer himself.

He is a cinematographer. So he shot, and he had his team, his camera operator, and it was great. I love working that way. It was similar to Quentin. You’ve got Bob Richardson — Bob’s the only one who shoots. It’s not like, “Okay we’re going to set up 35 cameras.” No. Bob Richardson, Quentin Tarantino, and I love it. Because it’s a singular voice on set. Paul’s the same way. He’s a singular voice. David Lynch is the same way too.

So when Paul called me, he’s like, “I had to cut the scene. But, I’m going to make other movies, and you’re going to be in them. And do you want to go see Licorice Pizza with me tomorrow — I’m going to go screen it to see how it looks.” So just Paul and I went, it was he and I in the theater watching Licorice Pizza with the editor, and I was laughing my ass off. And he said, “You laughed at all the right stuff.” And I said “Dude that fucking movie is great. It’s my childhood.” Because both Paul and I grew up in the valley. So I totally knew what he was doing.

One of my best friends trained with John Peters. So I said, “Dude, Brad Cooper’s playing John.” And I asked Paul, “Did you show John Peters the script?” And he’s like, “Oh fuck yeah. He loved it.” John was like, “Oh my god I’m such an asshole, this is perfect. That’s exactly how I used to be.” So he had John behind it, as opposed to doing it and John suffering the consequences. But I think Paul is brilliant. He’s such a kind human being, such a brilliant mind, and creates something different every single time. He’s a true filmmaker, and artist, and master, in my opinion.

Do you mean the scenes of violence?

Yeah yeah, and there was stuff that got cut out. Actually two big things that got cut out. When I read the script I was like, hmmmm, so I was happy when Paul cut it out. There’s a sequence with Alfred Molina, when he comes out all drugged-up.

That sequence continues to go on until the cops blow him away. So we did a full make-up on Alfred, with bullet hits and all that. Boom boom boom boom boom, with squibs, and then he dies. And if you remember, there was also talk of Johnny Wadd dying in a car accident in the movie. He’s the guy who replaces Mark Whalberg’s character, Dirk Diggler. That accident was with Dirk Diggler’s parents. And they’re dead at the scene and all that. And I just thought that was such a coincident thing, you know? We shot it all, but Paul cut both those scenes, and I thought that was awesome. I think it’s much better — but what the hell do I know: it’s Paul Thomas Anderson!

Anyhow, the big task was to make a large penis for Mark. Talking to Paul, he’s like “12 inches, man,” so we sculpt this 12-inch dick and all this stuff, and I do a test make-up with [KNB make-up artist] Garrett Immel and it’s way too big. Because Mark is actually like 5’7”, so it would look like it was 20-feet long. So I’m like, “Okay, we gotta redo this.” Garrett re-sculpted a 7-inch penis, which we tested on Mark, and that’s what we went with. So we had different versions, and actually in the movie we shot two scenes where you see it. One where he’s having sex with Amber Waves, Julianne Moore’s character, which got cut out, which is great, because Paul realized he was going to save it until the very end. We’ve been waiting the whole time to see what this is.

Paul Thomas Anderson is quoted as saying “When we were shooting it I kept thinking, This is exactly like seeing the dinosaur in Jurassic Park or seeing the shark in Jaws…” In other words, you created a monster!

It is. We keep waiting and waiting. You keep getting a promise. You keep hearing about it, but you never see it. And then Paul brilliantly reveals it at the end in the way that he does. It’s great.

I remember talking to Mark — this is before he was married and all that — but he was like, “You know Howard, the thing is, the next girl I go out with is going to be really disappointed.” We ended up giving it to him. He has it in a glass box at home, in a safe.

He keeps it in a safe?

Yeah yeah, I went over at some point and said, “Do you still have it?” And he’s like, “Yeah, right here,” and he opened up the safe and there it is, in a glass box. And I’m like, “Yep, that’s it.” We gave him the one we made. But that was cool, and that was really masterminded by Garrett Immel, who’s a great artist I work with all the time. It’s not the first penis we’ve done, and it won’t be the last.

So besides performing as a gorilla in Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes, you performed as a zombie in George Romero’s Day of the Dead, and as a vampire in the Tarantino-Robert Rodriguez collaboration, From Dusk Till Dawn. Given this resume as an occasional actor, I was wondering what your experience was like acting as an ordinary human character for Paul Thomas Anderson in Licorice Pizza? Rumor has it you acted in some scenes?

It was wonderful. It was probably one of my most favorite times on set. I was disappointed when Paul called me and was like, “Dude, I cut your scene because the movie’s running too long.” But we shot one day. It was three scenes with Cooper, who plays the lead.

And you’re not wearing make-ups?

No, I’m not wearing make-ups, although it was during the pandemic, so Paul’s like, “Let your beard grow, and let your hair grow.” And it did. So I got bushy and did my own make-up and hair. And yeah, I played a real guy named Omar, who was the guy who Gary had manufacture the water beds. I think Paul had that scene where Gary first sees the waterbeds and thought it was redundant to go back and have another scene. It was all good. The thing is, I got to be on set with Paul Thomas Anderson as director.

And what was that like?

It was magnificent. It was so much fun to see his giddiness and how happy he is, and what worked and didn’t work. You know, change these lines, and drop this paragraph, and add this. And working with Cooper — it was just myself and Cooper in the scenes. I felt like I worked really really hard, I was tired at the end of the day, but I was exhilarated. But Paul lets you run with it. There were some things he was married to, word-wise, but sometimes, if there was a line I didn’t remember but was able to reconfigure to make it fluid, he was great with it. But yeah, he's very organic. On this movie he didn’t have an official cinematographer.

He sounds like a cinematographer himself.

He is a cinematographer. So he shot, and he had his team, his camera operator, and it was great. I love working that way. It was similar to Quentin. You’ve got Bob Richardson — Bob’s the only one who shoots. It’s not like, “Okay we’re going to set up 35 cameras.” No. Bob Richardson, Quentin Tarantino, and I love it. Because it’s a singular voice on set. Paul’s the same way. He’s a singular voice. David Lynch is the same way too.

So when Paul called me, he’s like, “I had to cut the scene. But, I’m going to make other movies, and you’re going to be in them. And do you want to go see Licorice Pizza with me tomorrow — I’m going to go screen it to see how it looks.” So just Paul and I went, it was he and I in the theater watching Licorice Pizza with the editor, and I was laughing my ass off. And he said, “You laughed at all the right stuff.” And I said “Dude that fucking movie is great. It’s my childhood.” Because both Paul and I grew up in the valley. So I totally knew what he was doing.

One of my best friends trained with John Peters. So I said, “Dude, Brad Cooper’s playing John.” And I asked Paul, “Did you show John Peters the script?” And he’s like, “Oh fuck yeah. He loved it.” John was like, “Oh my god I’m such an asshole, this is perfect. That’s exactly how I used to be.” So he had John behind it, as opposed to doing it and John suffering the consequences. But I think Paul is brilliant. He’s such a kind human being, such a brilliant mind, and creates something different every single time. He’s a true filmmaker, and artist, and master, in my opinion.

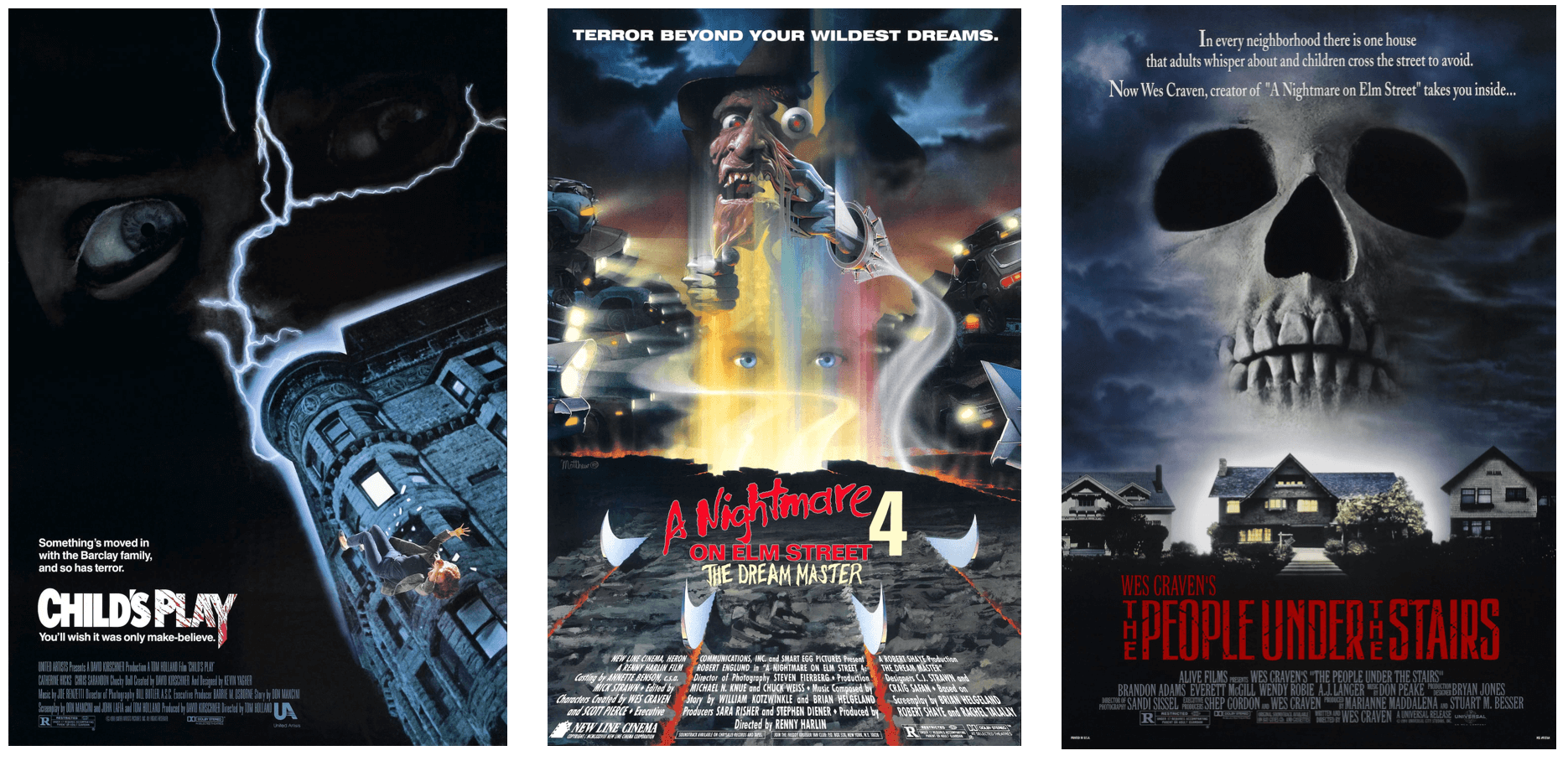

When you were in your early-20s, you cut your teeth working on some pretty iconic monsters, like the alien queen for Aliens, Freddy, Chucky. At that phase in your career as a make-up artist, just entering into it, what would you say are some of the core skills that are crucial to master as best you can, when you’re starting out?

I think the big thing is listen, and learn, and do what you’re asked to do. It’s not about you, you’re working as a team. So many people nowadays think it’s all about individuality and it’s not. You’re going to have better longevity if you know how to do everything. In my field, learn how to make molds, learn how to cast latex, learn how to make teeth, learn how to paint, how to sculpt. That way you’re going to be spread out. That’s how I would work for Stan Winston for years, or Kevin Yagher for years. I was good with whatever they wanted me to do because I knew I was there to do a job for them. It wasn’t about me, like “Oh, I should be sculpting those hands.” I didn’t care. I was so excited to be there and work for these people and just have the enthusiasm everyday to show up and do the best job I could for them. And my tasks were different.

At Stan Winston’s, one day I was making molds on the alien hands, and then the next day I’m helping fabricate the harness for the two people who are inside the queen’s body, and getting that ready for the big test. The garbage bag test.

I think the big thing is listen, and learn, and do what you’re asked to do. It’s not about you, you’re working as a team. So many people nowadays think it’s all about individuality and it’s not. You’re going to have better longevity if you know how to do everything. In my field, learn how to make molds, learn how to cast latex, learn how to make teeth, learn how to paint, how to sculpt. That way you’re going to be spread out. That’s how I would work for Stan Winston for years, or Kevin Yagher for years. I was good with whatever they wanted me to do because I knew I was there to do a job for them. It wasn’t about me, like “Oh, I should be sculpting those hands.” I didn’t care. I was so excited to be there and work for these people and just have the enthusiasm everyday to show up and do the best job I could for them. And my tasks were different.

At Stan Winston’s, one day I was making molds on the alien hands, and then the next day I’m helping fabricate the harness for the two people who are inside the queen’s body, and getting that ready for the big test. The garbage bag test.

Or the next day lifecasting one of the actors who’s going to one of the background drone aliens. It was whatever Stan asked us to do, or whoever was supervising — whatever they needed us to do, we did. There was never any begrudging or entitlement. We were just so happy to be there. Same with Rick Baker, when I worked at Rick Baker’s on Harry and the Hendersons, I was in the mold department. I couldn’t have been happier.

![]()

![]()

![Rick Baker make-up designs for Harry and the Hendersons (William Dear, 1987)]()

Everyday it was like, I hope I’m doing a good enough job for Rick. I just come from the school of I’ll do whatever you need me to do, because I know the final goal is that we end up with something super-cool. So, I just learned how to do everything, and I asked questions all the time. And even now I do. I’ll be on set and I’ll be like, How do you do that? Or what are you doing there? I’m not questioning their choice, I just want to learn, so that maybe I can try it next time. It’s always about learning.

![Howard Berger applying Kevin Yagher's Freddy makeup on Robert Englund for Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master (Renny Harlin, 1988)]()

You mentioned Kevin Yagher, who was one of the key designers of Freddy Kreuger’s make-up. There’s a nice passage in your book by Robert Englund, Freddy himself, which is interesting from the standpoint of acting. He says David Miller set the template for the Freddy make-up in the first Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). “David designed quite thick and heavy prosthetic pieces for me,” he says. Then:

I was fascinated by this passage. We’ve talked about acting a bit already, but I wonder what thoughts this passage calls to mind for you regarding the relation between actor and make-up?

It’s very important. It’s a partnership. I always try to prep the actor before we start creating. I let them know what I’m thinking, and how I would approach it, and make sure they’re on board. Because I’ve certainly had actors who are not on board, and that makes it a very difficult or unsatisfying experience. But I’ve been lucky. I’ve had actors like Tony Hopkins, James McAvoy, Robert Englund, and you work as a team. They understand that. I feel that as a make-up artist we bring X amount to the table, and they do the rest.

I remember the first test make-up I did on Tony Hopkins for Hitchcock. The make-up looked just like Alfred Hitchcock, but I had lost Tony in it. And Tony looked in the mirror and said, “I don’t even have to act.” And I said, “No no, of course you do because that’s what’s going to sell it.” But I ended up refining the make-up, making it less and less, and brought it to a combination. And Tony would ask questions about facial movements, and I would say, “Be careful if you move this part of your face, because there’s a little stress, so be careful how much you turn your head or compress and all that.” You work as a partnership because it is. It’s very collaborative.

![Howard Berger was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Make-Up and Hairstyling for his work on Hitchcock (Sacha Gervasi, 2012), starring Anthony Hopkins as the master of suspense.]()

![]()

I was interested in how, as an actor, your medium is both your inner life and your body and your voice, and how you bring characters to life through certain physical tics, and how make-up can actually inhibit that or not, which in turn might impact the way you express the character as an actor in performance.

You hope that it won’t impact, or that it impacts in a positive and not a negative way. Again it stems from working together. Going back to the Robert Englund passage, every movie they always try to say, We don’t need Robert, we not going to pay his rate, what he wants, his deal, so we’ll just get a stunt guy. And I remember on Nightmare 4, the first day of shooting, Robert didn’t come in. It was a stunt guy. So I called Kevin and said, Robert’s not here. What do you want me to do? He said just do the make-up on the stunt guy. We’re going to reshoot that anyhow. It’s going to be a fail. And it was! Because Robert has a distinct body performance. He has a thing and nobody else can do it. The same with Kane Hodder, who played Jason for Friday the 13th. He has very distinct body movements, and it’s that character. Robert has a very distinct style to his acting, the way Freddy walks — there’s a slither to it, and the stunt guy couldn’t do it. So after the first day of dailies, Bob Shaye, who was the head of New Line, said “This is crap. Pay Robert his deal, get him in here, and let’s reshoot this.” So we had to go back and reshoot in a junkyard, and Robert was like, I knew it. This happens every time. They try to save money, but they just blew an entire day of shooting. And they’ll never learn. But Robert is a great partner to work with. He’s so nice. One of the kindest people I’ve ever known. A great friend. I did Nightmare 4 while working for Kevin Yagher, Kevin let me do that make-up for him, represent him. And then I did the first season of Freddy’s Nightmares, and then Robert and I did a lot of touring, like for Halloween haunts and so forth. So it was really fun. I’ve had more great experiences with actors than bad experiences.

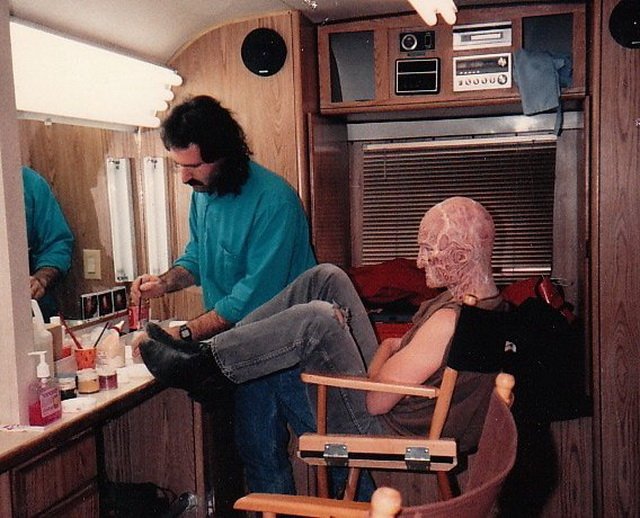

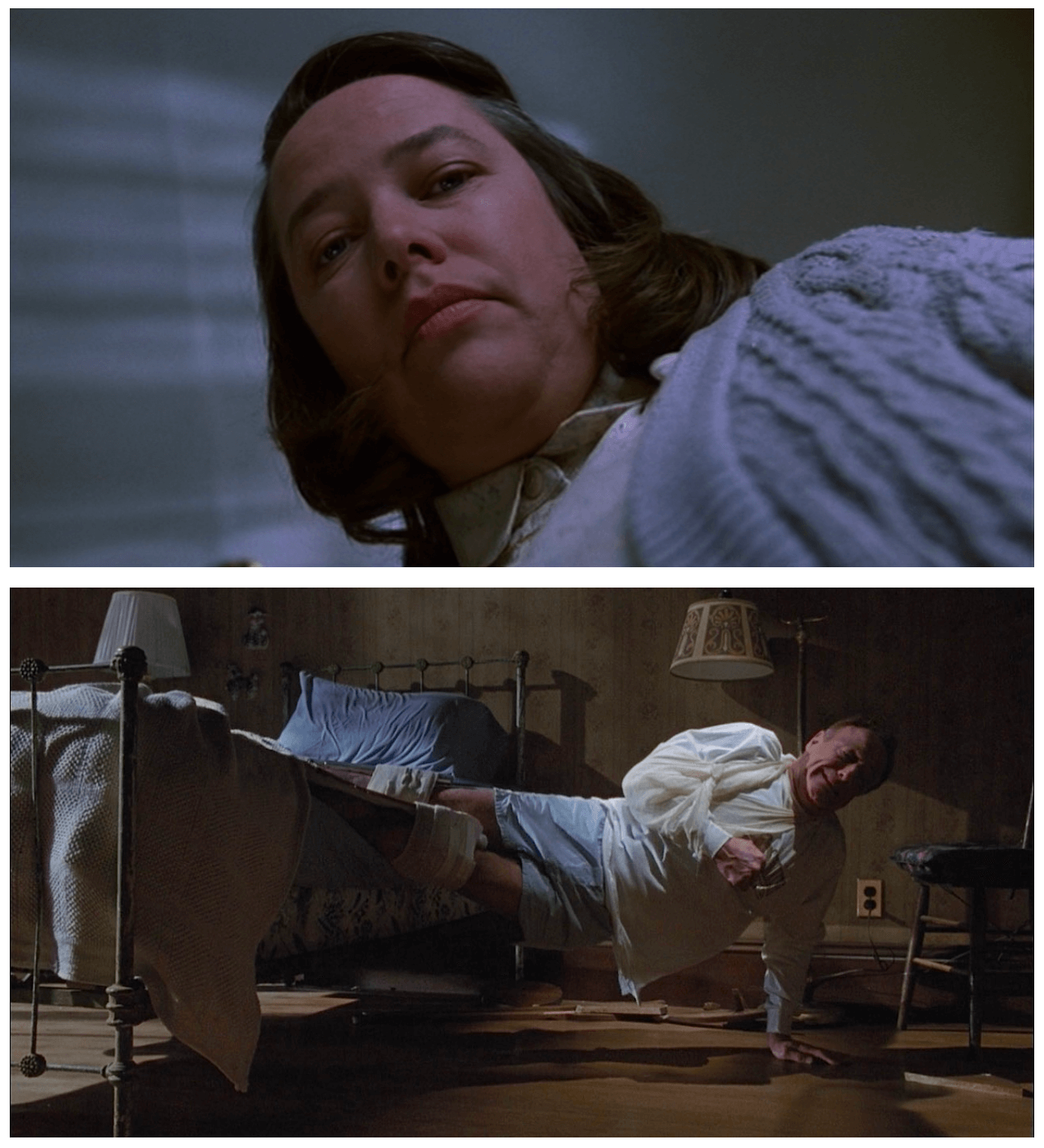

What was your experience like working on Misery (1990)? You designed a Hitchcock make-up, and this movie is very Hithcockian in its design.

Everyday it was like, I hope I’m doing a good enough job for Rick. I just come from the school of I’ll do whatever you need me to do, because I know the final goal is that we end up with something super-cool. So, I just learned how to do everything, and I asked questions all the time. And even now I do. I’ll be on set and I’ll be like, How do you do that? Or what are you doing there? I’m not questioning their choice, I just want to learn, so that maybe I can try it next time. It’s always about learning.

You mentioned Kevin Yagher, who was one of the key designers of Freddy Kreuger’s make-up. There’s a nice passage in your book by Robert Englund, Freddy himself, which is interesting from the standpoint of acting. He says David Miller set the template for the Freddy make-up in the first Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). “David designed quite thick and heavy prosthetic pieces for me,” he says. Then:

Later, on A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985), Kevin Yagher refined the make up and made it much lighter and easier to wear. It was porous. The foam latex breathed. Once everything was dry you didn’t feel anything at all.

To get David’s make-up moving, I had to make quite exaggerated gestures. With Kevin Yagher’s, it was like my own face: I’d wrinkle my brow, and Freddy would wrinkle his. David’s makeup was more dramatic, so great for wide shots. Kevin’s make-up was subtler, which meant it looked great in close-up, but for the wider shots I’d have to physicalize more. Freddy’s signature posture really grew out of that.

I was fascinated by this passage. We’ve talked about acting a bit already, but I wonder what thoughts this passage calls to mind for you regarding the relation between actor and make-up?

It’s very important. It’s a partnership. I always try to prep the actor before we start creating. I let them know what I’m thinking, and how I would approach it, and make sure they’re on board. Because I’ve certainly had actors who are not on board, and that makes it a very difficult or unsatisfying experience. But I’ve been lucky. I’ve had actors like Tony Hopkins, James McAvoy, Robert Englund, and you work as a team. They understand that. I feel that as a make-up artist we bring X amount to the table, and they do the rest.

I remember the first test make-up I did on Tony Hopkins for Hitchcock. The make-up looked just like Alfred Hitchcock, but I had lost Tony in it. And Tony looked in the mirror and said, “I don’t even have to act.” And I said, “No no, of course you do because that’s what’s going to sell it.” But I ended up refining the make-up, making it less and less, and brought it to a combination. And Tony would ask questions about facial movements, and I would say, “Be careful if you move this part of your face, because there’s a little stress, so be careful how much you turn your head or compress and all that.” You work as a partnership because it is. It’s very collaborative.

I was interested in how, as an actor, your medium is both your inner life and your body and your voice, and how you bring characters to life through certain physical tics, and how make-up can actually inhibit that or not, which in turn might impact the way you express the character as an actor in performance.

You hope that it won’t impact, or that it impacts in a positive and not a negative way. Again it stems from working together. Going back to the Robert Englund passage, every movie they always try to say, We don’t need Robert, we not going to pay his rate, what he wants, his deal, so we’ll just get a stunt guy. And I remember on Nightmare 4, the first day of shooting, Robert didn’t come in. It was a stunt guy. So I called Kevin and said, Robert’s not here. What do you want me to do? He said just do the make-up on the stunt guy. We’re going to reshoot that anyhow. It’s going to be a fail. And it was! Because Robert has a distinct body performance. He has a thing and nobody else can do it. The same with Kane Hodder, who played Jason for Friday the 13th. He has very distinct body movements, and it’s that character. Robert has a very distinct style to his acting, the way Freddy walks — there’s a slither to it, and the stunt guy couldn’t do it. So after the first day of dailies, Bob Shaye, who was the head of New Line, said “This is crap. Pay Robert his deal, get him in here, and let’s reshoot this.” So we had to go back and reshoot in a junkyard, and Robert was like, I knew it. This happens every time. They try to save money, but they just blew an entire day of shooting. And they’ll never learn. But Robert is a great partner to work with. He’s so nice. One of the kindest people I’ve ever known. A great friend. I did Nightmare 4 while working for Kevin Yagher, Kevin let me do that make-up for him, represent him. And then I did the first season of Freddy’s Nightmares, and then Robert and I did a lot of touring, like for Halloween haunts and so forth. So it was really fun. I’ve had more great experiences with actors than bad experiences.

What was your experience like working on Misery (1990)? You designed a Hitchcock make-up, and this movie is very Hithcockian in its design.

It was cool. We’re going to do this movie with James Caan and Rob Reiner’s going to direct it.

It was the last film Barry Sonnenfeld shot as a cinematographer. The camerawork and editing are incredible.

Barry Sonnenfeld, yep, very last film he shot. It was interesting because I was on that set and Greg Nicotero was on the same studio lot doing Sibling Rivalry, which Carl Reiner was directing. I had Rob, he had Carl. We would see each other at lunch and he’s like, “This is the most fun — Carl’s so great!” And I would say, “This is literally miserable. Rob is so, ugh. Ask Carl what he did to Rob, because I don’t understand.” Rob was still trying to figure out what the movie was. He would say, I don’t know what I’m making, I don’t know what this movie is. But half-way through the movie it clicked, and Rob was great. We did a bunch of stuff. We did the legs, the hobbling. What everyone remembers is the hobbling.

So we did a make-up on James Caan, which had different stages. We also had the make-up after the hobbling. He had a personal make-up artist, John Elliot, who did his face. But I handled his legs and all that stuff. And then, at the end of the movie, when Kathy’s character is getting killed, we built all these different heads of Kathy in different expressions.

In different expressions so that there would be options?

Well they were different heads for different things. We had a head for a typewriter hit — bam. We built a puppet head of her that takes that one. Then there’s one for shoving papers down her throat. Then there’s one for punching her in the face. So we had all these different puppet heads of Kathy, and they were all in the trailer. And she came in and said, “These are disturbing, Howard, can you cover them up?” It was a hard movie. I was pretty much on set by myself on that one. But it turned out great. We went to the cast/crew screening and thought, This is a really great film. Rob’s brilliant, as we knew.

Incidentally, speaking of heads, the first couple films of yours that I revisited when starting to prepare for this conversation both involved decapitations.

Kill Bill has a lot of decapitations.

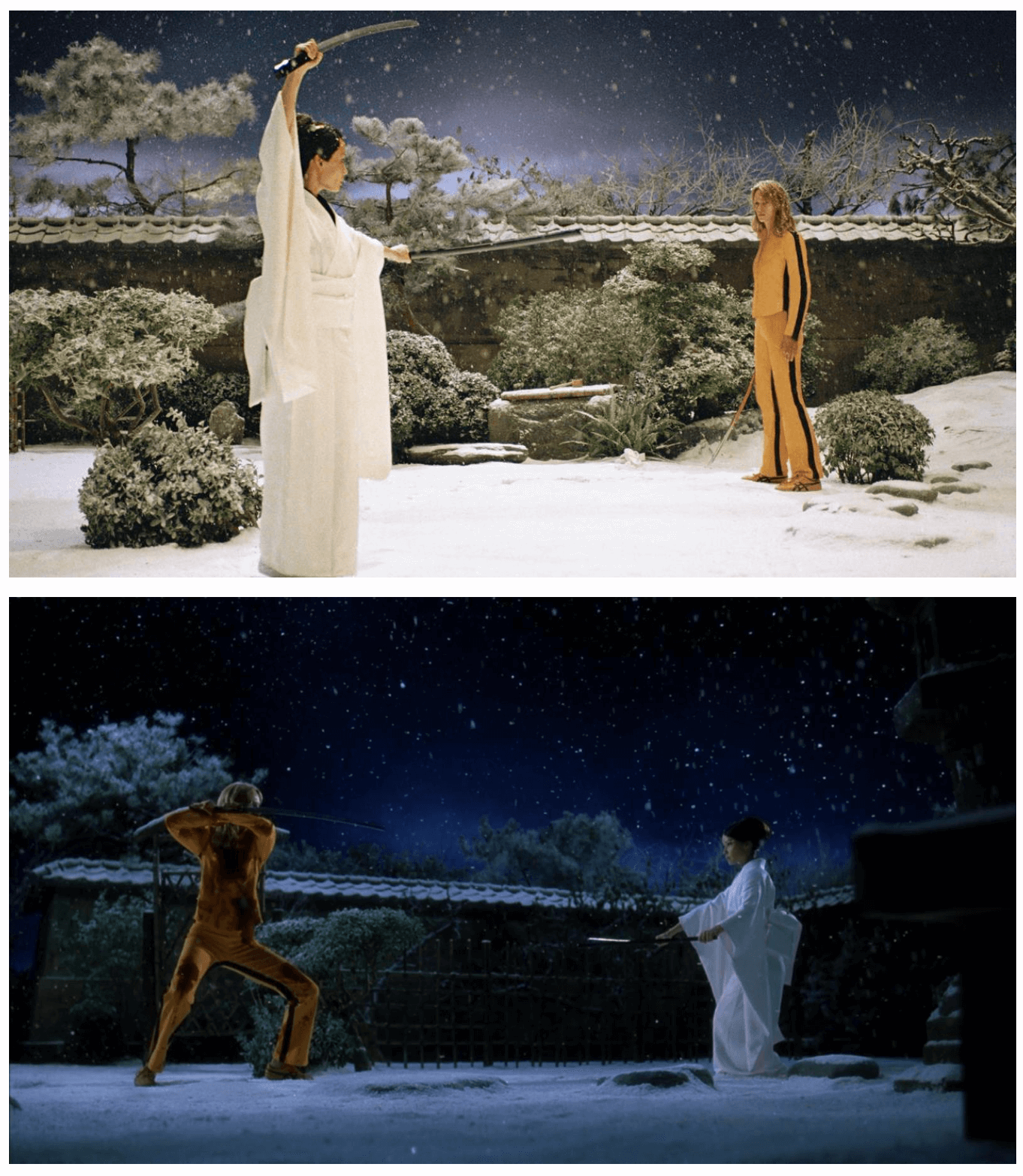

I think you’ve worked on every Quentin Tarantino movie. I heard you mention in some context that Kill Bill changed your brain? I wonder what you meant?

That experience was something magical. Shooting in China, with Quentin. I came back different. Even my ex-wife said so. But something happened to my brain over there, in a good way. I opened up and saw things differently. When we went to do Kill Bill, Chris Nelson, myself, and Jake McKinnon were supposed to go for three weeks and we ended up staying for seven months, shooting and shooting. Quentin loved it there. So we shot, and did tons of blood gags. The House of Blue Leaves sequence went on for three or four months, and then we stayed to shoot more stuff. Quentin loved to shoot in China. Every experience with Quentin I love. He’s my favorite director to work with because he’s just so full of energy and great thoughts. It’s very challenging and very difficult on set, but every night I would go home and felt like I accomplished so much. It was very rewarding working for Quentin Tarantino.

Is it the enthusiasm, or are there other things about the way he manages or orchestrates his set that makes him a good director?

I would watch him direct actors. That was very interesting. He would direct each actor very differently, because each actor is a very different person. The way he dealt with Uma was different, the way he dealt with Lucy was different, the way he dealt with Madsen was different, the way he dealt with David was different. He has that sense of how to direct each person. It’s not one style of directing on any level. And he’s pretty goddamned brilliant. Plus you trust him, you trust Quentin Tarantino. That’a big thing nowadays with directors. I don’t trust them, because I bring my A-game and then I see the finished product and I’m like, that is dogshit. So they failed me. The crew delivered, and the one person who didn’t is that guy there sitting in the chair that says director. You can smell it when you’re on set nowadays. There are a lot of people who have been given chances, and I think that’s wonderful. But if they’re not ready, they shouldn’t be doing it. So many times I’ll ask students, “What do you want to do?” “I want to be a director.” “Well have you directed anything?” “Not yet.” “Do you have an iPhone?” “I do.” “Then go fucking direct something, go shoot a movie with your iPhone this weekend and cut it together. It’s easy.” But, you know, they still have this dream. People are so afraid of failing, but failing is a massive part of learning. I say it all the time: if you don’t fail, you don’t learn shit.

I’m curious about Mulholland Drive. Were you involved in the making of that movie?

Yeah yeah, just weird shit. David always likes weird stuff. I just watched it recently, my wife and I said, “Let’s watch Mulholland Drive.” He would just tell me what he needed, like “Hey Howard, I need a dead body in the bed that’s in this position.”

You did the dead body of Diane Selwyn?

Yeah we did a lot of stuff. There’s a lot of stuff in that movie that no one will ever know. We did Michael Anderson, who’s in the wheelchair. We built this full-size body. David was great. But I didn’t know how anything played. Originally, Mulholland Drive was a pilot. ABC said “We don’t like it, we don’t want it.” So David said “Okay fine,” and then turned it into this incredible movie. The thing about David, I find, is that there are a lot of happy accidents. Sometimes things are not premeditated. They happen, and David will integrate it into his movies, and people will then read all this shit into it. But maybe he just liked the way it felt out of focus. He’s just that kind of guy. He’s an amazing human being. I’ve stayed friends with him. I tried to get him to write the “Forward” to the new book, but he was like, “Howard I don’t want to do it, I’ll screw it up.” And I’m like, “C’mon David, please?” And he said, “I appreciate it, but I’m not any good at this.” I said “Okay, I respect that.” I respect the shit out of him. And I’ve done a bunch of personal projects for David through the years. He might have an idea, like “Hey Howard, I’d like to do …” just crazy stuff.

Like what? What would be an example of an assignment he gave you?

I’ll tell you one of the assignments. This was a long time ago. He said, “I have this idea I want to shoot. I want to have a body sitting in a chair, and I want the body packed with meat and blood, and then I’m going to have cameras rolling all night long. Come to my house, we’re going to shoot in the back yard. We’re going to wait for animals to come and just devour it.” And I remember he said, “And maybe an owl will swoop down and pull the eye out!”

So we were all at David’s house all night long, but nothing happened. A friend of mine, Mike McCarty, and I had made a head and packed it full of meat and shit and had eyeballs in it, the thing was full of blood, but no animal went near it. Crazy things like that, you know, but it was fun — because it’s for David. Whatever David wants; I would do anything in the world for David Lynch, because he is truly a genius.

Amazing. Okay just one last question for now, but this one’s about music. Do you have any favorite movie scores? Or are there any movie scores you would recommend for the Halloween season?

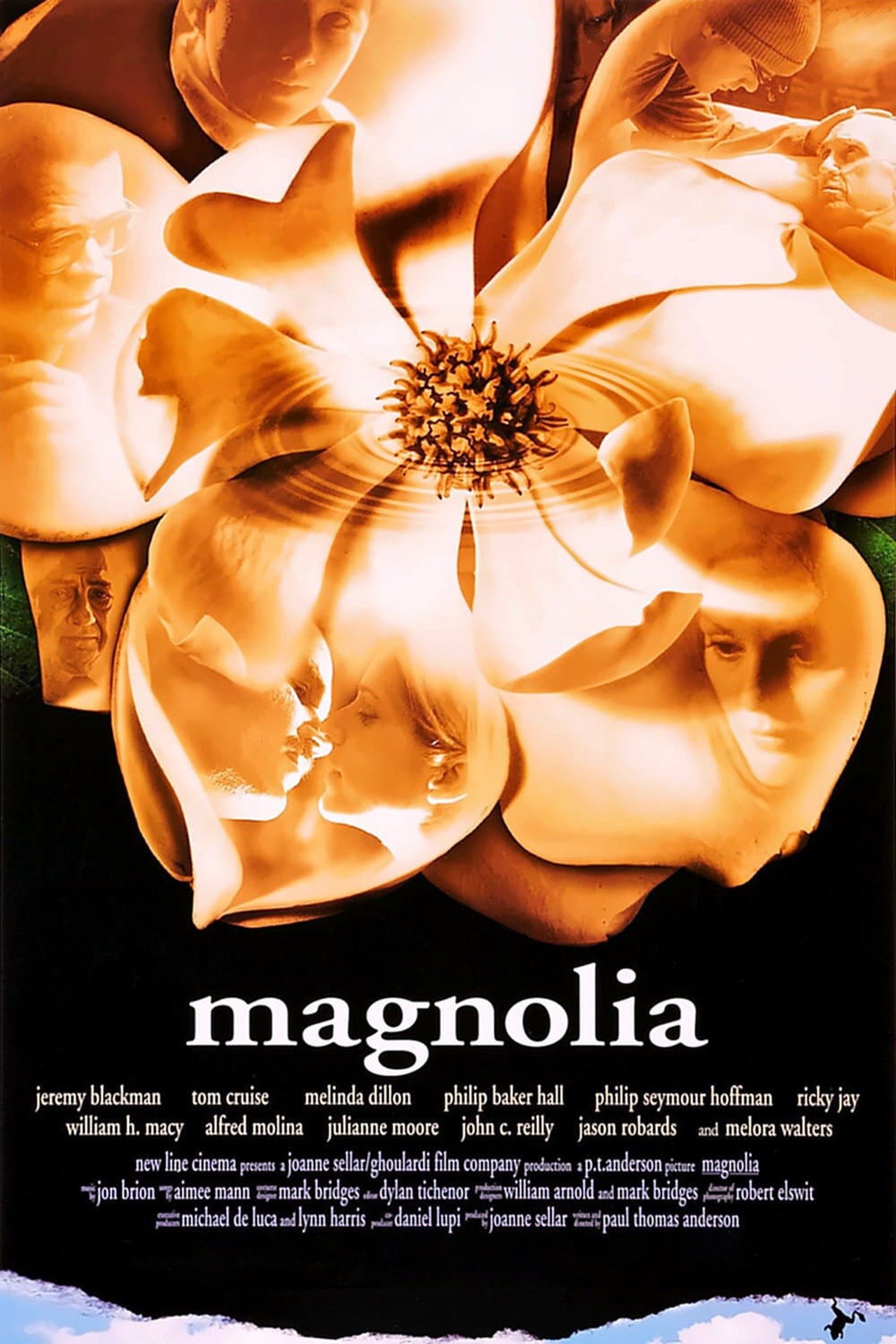

I love movie music. I’m obsessed with scores. One of my all-time favorite scores is Jon Brion’s score for Magnolia, which is outstanding. I listen to it all the time. It really is beautiful music.

And if you’re talking about Halloween, to me the ultimate piece of music is John Carpenter’s Halloween. That piece — that movie — captures the season. For me that movie is the only true Halloween movie. I don’t mean in terms of the franchise and all the sequels and yada yada yada. I’m saying you could watch that film on Christmas and it will feel like it’s Halloween time. It’s the way John captured the actual season of Halloween, and Fall. You watch that movie and you’re like, I’m in Halloween, I’m in that season. It’s the only one. And when you hear that music, your hair stands up on the back of your neck.

A perfect note to end on. Thank you so much for sharing these stories Howard, and for all your contributions to movie magic. Happy Halloween!