Serge Daney

The Monster is Afraid

+

Night of the Living Dead

The following two reviews were written by the late Serge Daney, widely regarded as one of the most important movie critics and cinephiles of post-68 France. Daney edited Cahiers du Cinéma from 1974-1981, wrote for Libération from 1981 to 1991, and co-founded the publication Trafic in 1991, a year before he died of AIDS-related causes. Daney collaborated with Jean-Luc Godard on the epic Histoires du cinéma (1988-1998; see Chapter 2A), and with Claire Denis on the 1990 documentary Jacques Rivette, le veilleur (Rivette’s 1961 review of Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò made an indelible impact on Daney, as summarized in one of Daney’s final and most important texts, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò”).

Daney’s writings were unavailble in English translation for many years. The following two reviews (the first favorable, the second less so) are included in the recently published, 600-page Serge Daney: The Cinema House and The World: The Cahiers du Cinéma Years, 1962-1981, edited by Patrice Rollet with Jean-Claude Biette and Christophe Manon, translated by Christine Pichini, with an introduction by A.S. Hamrah, published and reproduced here courtesy of Semiotext(e).

The Monster is Afraid

David Lynch, The Elephant Man

It’s the Monster Who Is Afraid

This film is strange in so many ways. Beginning with what David Lynch does with fear. That of the spectator (ours) and that of his characters, including John Merrick (the elephant-man). In this way the first section of the film, up until the move to the hospital, operates a little like a trap. The spectator becomes accustomed to the idea that he must sooner or later endure the unendurable and look the monster in the face. A coarse burlap sack, pierced with a single eyehole is all that separates him from the horror he suspects. The spectator entered the film, following Treves, through voyeurism. He paid (just like Treves) to see a freak: this elephant-man alternately exhibited and prohibited, rescued and beaten, glimpsed in a cellar, “presented” to savants, taken in and hidden at the royal Hospital of London. And when the spectator finally does see him, he is all the more disappointed that Lynch then pretends to play the classic horror film game: night, deserted hospital corridors, the witching hour, the rapid flight of clouds beneath a leaden sky and suddenly a shot of John Merrick bolt upright in bed, in the throes of a nightmare. He sees him—truly—for the first time, but he also sees that this monster who is supposed to terrify him is himself terrified. It’s at that moment that Lynch liberates his spectator from the trap that he initially set (the trap of “more-to-see”), as if he were saying, “it’s not you who matters, it’s the elephant-man; it’s not your fear that interests me, it’s his; it’s not your fear of being afraid that I want to manipulate, it’s his fear of inspiring fear, the fear he has of seeing himself in the other’s eyes.” Vertigo switches sides.

The Psalm Is a Mirror

The Elephant Man is a series of dramatic turns, some funny (the princess’s visit to the hospital, as a “deus ex machina”), others more troubling. We never know how a scene might end. When Treves wants to convince Carr Gomm, the director of the hospital (played magnificently by John Gielgud), that John Merrick is not incurable, he asks Merrick to memorize and recite the beginning of a psalm: barely have the two doctors left the room when they hear Merrick recite the end of the psalm. Shock, dramatic turn: this man that Treves himself believed to be a cretin knows the Bible by heart. Later, when Treves introduces him to his wife, Merrick continues to surprise them by showing them a portrait of his own mother (who is very beautiful) and by being first to extend a handkerchief to Treves’s wife, who has suddenly burst into tears. There is a lot of comedy in the way that the elephant man is inscribed as the one who always completes the tableau he is a part of, signs it. It is also a very literal way, not at all psychological, of moving the story forward: by leaps and bounds, by a signifying logic. That is how John Merrick finds his place within the portrait of (high) English society, Victorian and puritan, for which he becomes a sort of touristic must. He is something that society needs, something without which it is incomplete. But what exactly? The end of the psalm, the portrait, the handkerchief, what are they, ultimately? As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that for those surrounding him, the elephant-man is a mirror: they see him less and less, but they see themselves more and more in his eyes.

The Three Gazes

Throughout the film, John Merrick is the object of three gazes. Three gazes, three cinematic eras: burlesque, modern, classical. Or: the carnival, the hospital, the theater. There is first the gaze from the bottom, of the lower classes and Lynch’s gaze (hard, precise, abrasive) upon that gaze. There are bits of carnival, in the scene where Merrick is made drunk and is kidnapped. In the carnivalesque, there is no human essence to embody (even in monster form), there is a body to laugh at. next there is the modern gaze, the gaze of the fascinated doctor, Treves (Anthony Hopkins, remarkable): respect for the other and bad conscience, morbid eroticism and epistemophilia. By caring for the elephant-man, Treves saves himself: it’s the fight of the humanist (à la Kurosawa). Lastly, there is a third gaze. The more well-known and celebrated the elephant-man becomes, the more time those who visit him have to make a mask for themselves, a mask of politeness that conceals what they feel at the sight of him. They go to see John Merrick to test this mask: if they show their fear, they will see its reflection in Merrick’s eyes. That is how the elephant-man is their mirror: not a mirror in which they can see, recognize themselves, but a mirror to learn how to perform, to dissimulate, to lie even more. At the beginning of the film, there was the abject promis- cuity between the freak and the showman (Bytes), then there was the silent, ecstatic horror of Treves in the cellar. At the end, it’s Mrs. Kendal, star of the London theater, who decides, while reading the newspaper, to become the elephant-man’s friend. In an unnerving scene, Anne Bancroft, guest-star, wins the bet: nary a muscle in her face trembles when she is introduced to Merrick, whom she speaks to as if he were an old friend, going even so far as to kiss him. The circle is complete; Merrick can die and the film can end. On the one hand, the social mask is entirely reconstructed; on the other, Merrick has finally seen in the other’s gaze something entirely different than the reflection of the disgust he inspires. What? He cannot say. He takes the height of artifice as truth and, of course, he is not wrong, considering we are at the theater.

For the elephant-man nourishes two dreams: to sleep on his back and to go to the theater. He will realize both on the same night, just before he dies. The end of the film is very moving. At the theater, when Merrick stands up in his loge so the people who are applauding him can see him more clearly, we don’t really know what’s in their eyes any longer, we no longer know what they see. And so Lynch has managed to redeem one by the other, dialectically, the monster and society. But only at the theater, only for one night. There will be no other performance.

(Cahiers du Cinéma #322, April 1981)

Translated by Christine Pichini

It’s the Monster Who Is Afraid

This film is strange in so many ways. Beginning with what David Lynch does with fear. That of the spectator (ours) and that of his characters, including John Merrick (the elephant-man). In this way the first section of the film, up until the move to the hospital, operates a little like a trap. The spectator becomes accustomed to the idea that he must sooner or later endure the unendurable and look the monster in the face. A coarse burlap sack, pierced with a single eyehole is all that separates him from the horror he suspects. The spectator entered the film, following Treves, through voyeurism. He paid (just like Treves) to see a freak: this elephant-man alternately exhibited and prohibited, rescued and beaten, glimpsed in a cellar, “presented” to savants, taken in and hidden at the royal Hospital of London. And when the spectator finally does see him, he is all the more disappointed that Lynch then pretends to play the classic horror film game: night, deserted hospital corridors, the witching hour, the rapid flight of clouds beneath a leaden sky and suddenly a shot of John Merrick bolt upright in bed, in the throes of a nightmare. He sees him—truly—for the first time, but he also sees that this monster who is supposed to terrify him is himself terrified. It’s at that moment that Lynch liberates his spectator from the trap that he initially set (the trap of “more-to-see”), as if he were saying, “it’s not you who matters, it’s the elephant-man; it’s not your fear that interests me, it’s his; it’s not your fear of being afraid that I want to manipulate, it’s his fear of inspiring fear, the fear he has of seeing himself in the other’s eyes.” Vertigo switches sides.

The Psalm Is a Mirror

The Elephant Man is a series of dramatic turns, some funny (the princess’s visit to the hospital, as a “deus ex machina”), others more troubling. We never know how a scene might end. When Treves wants to convince Carr Gomm, the director of the hospital (played magnificently by John Gielgud), that John Merrick is not incurable, he asks Merrick to memorize and recite the beginning of a psalm: barely have the two doctors left the room when they hear Merrick recite the end of the psalm. Shock, dramatic turn: this man that Treves himself believed to be a cretin knows the Bible by heart. Later, when Treves introduces him to his wife, Merrick continues to surprise them by showing them a portrait of his own mother (who is very beautiful) and by being first to extend a handkerchief to Treves’s wife, who has suddenly burst into tears. There is a lot of comedy in the way that the elephant man is inscribed as the one who always completes the tableau he is a part of, signs it. It is also a very literal way, not at all psychological, of moving the story forward: by leaps and bounds, by a signifying logic. That is how John Merrick finds his place within the portrait of (high) English society, Victorian and puritan, for which he becomes a sort of touristic must. He is something that society needs, something without which it is incomplete. But what exactly? The end of the psalm, the portrait, the handkerchief, what are they, ultimately? As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that for those surrounding him, the elephant-man is a mirror: they see him less and less, but they see themselves more and more in his eyes.

The Three Gazes

Throughout the film, John Merrick is the object of three gazes. Three gazes, three cinematic eras: burlesque, modern, classical. Or: the carnival, the hospital, the theater. There is first the gaze from the bottom, of the lower classes and Lynch’s gaze (hard, precise, abrasive) upon that gaze. There are bits of carnival, in the scene where Merrick is made drunk and is kidnapped. In the carnivalesque, there is no human essence to embody (even in monster form), there is a body to laugh at. next there is the modern gaze, the gaze of the fascinated doctor, Treves (Anthony Hopkins, remarkable): respect for the other and bad conscience, morbid eroticism and epistemophilia. By caring for the elephant-man, Treves saves himself: it’s the fight of the humanist (à la Kurosawa). Lastly, there is a third gaze. The more well-known and celebrated the elephant-man becomes, the more time those who visit him have to make a mask for themselves, a mask of politeness that conceals what they feel at the sight of him. They go to see John Merrick to test this mask: if they show their fear, they will see its reflection in Merrick’s eyes. That is how the elephant-man is their mirror: not a mirror in which they can see, recognize themselves, but a mirror to learn how to perform, to dissimulate, to lie even more. At the beginning of the film, there was the abject promis- cuity between the freak and the showman (Bytes), then there was the silent, ecstatic horror of Treves in the cellar. At the end, it’s Mrs. Kendal, star of the London theater, who decides, while reading the newspaper, to become the elephant-man’s friend. In an unnerving scene, Anne Bancroft, guest-star, wins the bet: nary a muscle in her face trembles when she is introduced to Merrick, whom she speaks to as if he were an old friend, going even so far as to kiss him. The circle is complete; Merrick can die and the film can end. On the one hand, the social mask is entirely reconstructed; on the other, Merrick has finally seen in the other’s gaze something entirely different than the reflection of the disgust he inspires. What? He cannot say. He takes the height of artifice as truth and, of course, he is not wrong, considering we are at the theater.

For the elephant-man nourishes two dreams: to sleep on his back and to go to the theater. He will realize both on the same night, just before he dies. The end of the film is very moving. At the theater, when Merrick stands up in his loge so the people who are applauding him can see him more clearly, we don’t really know what’s in their eyes any longer, we no longer know what they see. And so Lynch has managed to redeem one by the other, dialectically, the monster and society. But only at the theater, only for one night. There will be no other performance.

(Cahiers du Cinéma #322, April 1981)

Translated by Christine Pichini

Night of the Living Dead

George A. Romero, Night of the Living Dead

Not enough attention has been paid to American cinema’s persistent, underground love for the apocalypse. As if too much self-righteousness could only be extended by evoking the most definitive horrors, horrors accompanied by a certain kind of pleasure, as we had previously seen in the films of DeMille (or in King’s In Old Chicago, Van Dyke’s San Francisco), a filmmaker of catastrophe and disaster, themes whose remarkable severity cannot be overlooked and whose yield is not insignificant, as the photogeneity of total destruction is complemented by the secondary benefits of the characters’ rehabilitation (those characters who survive it, at least), characters who, after having been broken, are more sublime and human than they ever were before. Major natural disasters and the crucibles that a shallow society deserves: such was the case with DeMille, as it was later with Hitchcock, or with the low-budget sci-fi films suddenly made possible, towards 1950, by the idea of an atomic end, the abrupt mutations of nature in revolt, aberrant and monstrous, the always possible eradication of mankind, etc. (Five, Them!, Body Snatchers, etc.). And yet, here as elsewhere, the apocalypse was a disappointment because mankind, having been stupid enough to deserve it, was also smart enough to stop it, opposing it with a united front from which, all differences having been temporarily erased, an overwhelming sense of humanity emerged. Humanity per se, meaning not monstrous.

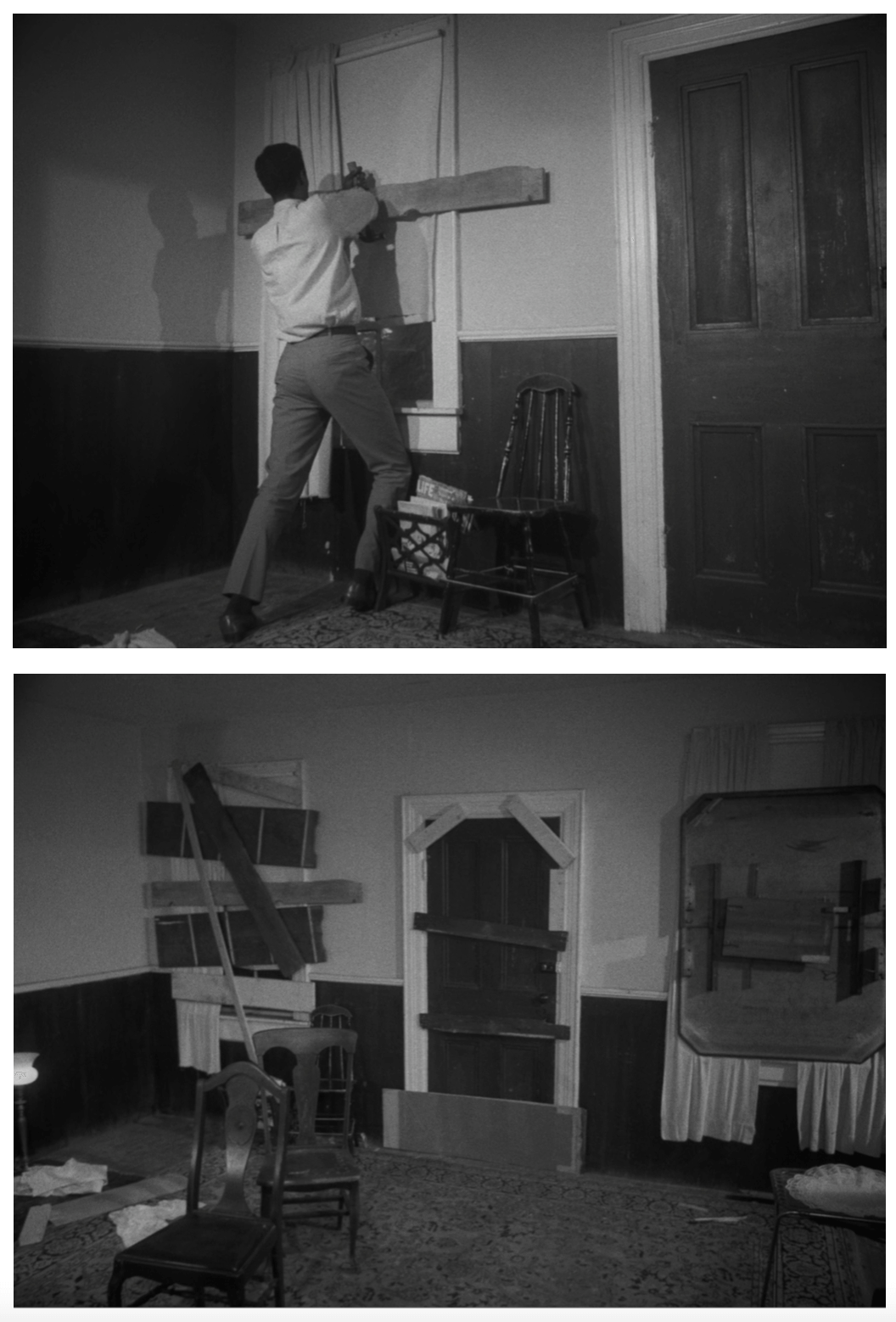

If it is true that Romero intends to keep his distance from that cinematic tradition, we must acknowledge that he begins by respecting it. The script contains no surprises: as an unanticipated aftereffect of a botched space probe, the brains of the most recent dead are reactivated, and the cadavers take advantage of their return to life to feed on living flesh. Appropriately, the generality of the phenomenon is rendered by the choice of an exclusive space—an isolated house that is attacked by the monsters overnight and eventually invaded—that is connected to the outside world only by a television set. After a brutal night, while the living dead die again, the film’s hero and sole survivor, a Black man (Ben), the director and heart of the resistance, is mistaken for a zombie and is killed. This would simply be a ludicrous joke if the following shots didn’t contain photos of his corpse on the front page of the newspapers, photos of a model zombie.

Here, then, we have a simplistic, tacked-on ending that does little to convince us. Because of it, we are suddenly miles away from the pleasant feelings we had anticipated, and forced to question the real subject of the film, which clearly is not zombies, but racism. Because of it, a retrospective reading of the film seems legitimate. And yet, such a reading, if we were to attempt it, would have nothing to draw upon, wouldn’t mitigate the film’s heterogeneity, heterogeneity that is the force of a film whose conclusion serves as an answer to a question that hasn’t been asked, the denunciation of a problem that was poorly stated. For not only is there no mention of racism in the film, but during the most violent clashes between Ben and Cooper (white and despicable), it is frankly unbelievable that Cooper wouldn’t resort to using racist slurs. Instead, it is as if throughout the film the characters and the filmmakers consider Ben as simply a man, nothing more, without his skin color causing any problems for even a second. The problem is assumed to be resolved, even transcended. And it is assumed that the spectator will blindly follow, thrilled that he may enjoy his tolerance and generosity of spirit at such a low cost. Everything seems to allow for a humanizing reading of the film that Romero absolutely facilitates before he parasitizes it and calls it what it is: a way to invoke the monstrous in order to avoid speaking about the simple differences that exist between men, to obscure them by confronting them to a difference as enormous as it is imaginary.

One might say that this gives too much credit to Romero, whose film is clumsily shot, awkwardly acted and as for being scary, completely ineffective; it is enough for us that the film produces this call to order.

(Cahiers du Cinéma #219, April 1970)

Translated by Christine Pichini

Not enough attention has been paid to American cinema’s persistent, underground love for the apocalypse. As if too much self-righteousness could only be extended by evoking the most definitive horrors, horrors accompanied by a certain kind of pleasure, as we had previously seen in the films of DeMille (or in King’s In Old Chicago, Van Dyke’s San Francisco), a filmmaker of catastrophe and disaster, themes whose remarkable severity cannot be overlooked and whose yield is not insignificant, as the photogeneity of total destruction is complemented by the secondary benefits of the characters’ rehabilitation (those characters who survive it, at least), characters who, after having been broken, are more sublime and human than they ever were before. Major natural disasters and the crucibles that a shallow society deserves: such was the case with DeMille, as it was later with Hitchcock, or with the low-budget sci-fi films suddenly made possible, towards 1950, by the idea of an atomic end, the abrupt mutations of nature in revolt, aberrant and monstrous, the always possible eradication of mankind, etc. (Five, Them!, Body Snatchers, etc.). And yet, here as elsewhere, the apocalypse was a disappointment because mankind, having been stupid enough to deserve it, was also smart enough to stop it, opposing it with a united front from which, all differences having been temporarily erased, an overwhelming sense of humanity emerged. Humanity per se, meaning not monstrous.

If it is true that Romero intends to keep his distance from that cinematic tradition, we must acknowledge that he begins by respecting it. The script contains no surprises: as an unanticipated aftereffect of a botched space probe, the brains of the most recent dead are reactivated, and the cadavers take advantage of their return to life to feed on living flesh. Appropriately, the generality of the phenomenon is rendered by the choice of an exclusive space—an isolated house that is attacked by the monsters overnight and eventually invaded—that is connected to the outside world only by a television set. After a brutal night, while the living dead die again, the film’s hero and sole survivor, a Black man (Ben), the director and heart of the resistance, is mistaken for a zombie and is killed. This would simply be a ludicrous joke if the following shots didn’t contain photos of his corpse on the front page of the newspapers, photos of a model zombie.

Here, then, we have a simplistic, tacked-on ending that does little to convince us. Because of it, we are suddenly miles away from the pleasant feelings we had anticipated, and forced to question the real subject of the film, which clearly is not zombies, but racism. Because of it, a retrospective reading of the film seems legitimate. And yet, such a reading, if we were to attempt it, would have nothing to draw upon, wouldn’t mitigate the film’s heterogeneity, heterogeneity that is the force of a film whose conclusion serves as an answer to a question that hasn’t been asked, the denunciation of a problem that was poorly stated. For not only is there no mention of racism in the film, but during the most violent clashes between Ben and Cooper (white and despicable), it is frankly unbelievable that Cooper wouldn’t resort to using racist slurs. Instead, it is as if throughout the film the characters and the filmmakers consider Ben as simply a man, nothing more, without his skin color causing any problems for even a second. The problem is assumed to be resolved, even transcended. And it is assumed that the spectator will blindly follow, thrilled that he may enjoy his tolerance and generosity of spirit at such a low cost. Everything seems to allow for a humanizing reading of the film that Romero absolutely facilitates before he parasitizes it and calls it what it is: a way to invoke the monstrous in order to avoid speaking about the simple differences that exist between men, to obscure them by confronting them to a difference as enormous as it is imaginary.

One might say that this gives too much credit to Romero, whose film is clumsily shot, awkwardly acted and as for being scary, completely ineffective; it is enough for us that the film produces this call to order.

(Cahiers du Cinéma #219, April 1970)

Translated by Christine Pichini