Masha Tupitsyn

DECADES: 80s

DECADES: 80s

2019, 6 hours, 19 minutes

In the 20th century, every decade had its own themes, colors, tones, moods, and sounds. A decade (from the Greek déka—δέκα—meaning "ten") is a 20th century phenomenology and bracket of time. Prior to cinema and television, it was perhaps centuries that mattered.

Today neither centuries nor decades exist, which means we have lost time. A way of looking at, remembering, measuring, and understanding both the world and our lives.

In retrospect, it seems clear from the vantage point of the 21st century that 20th century cinema is both verité and spectral because it is a record of all the things that no longer exist. More precisely, it is a testament to what has been destroyed: cities, ways of living, daily rhythms, social fabrics, attention. To watch old movies—the 21st century makes everything look “old”—is to encounter a lost world.

Like my earlier film LOVE SOUNDS (2015), DECADES is a technology produced and circulated by other technologies. Using the found material of film scores and diegetic sound to build a unique soundtrack for an entire decade, DECADES, an ongoing durational series, is a portrait of time. It proposes that the way we experienced cultural shifts in the 20th century was not simply visual or narrative, but tonal. Like LOVE SOUNDS, a 24-hour film which used audio (dialogue) from movies to compose a spoken history of love in English-speaking cinema, DECADES utilizes film score and film sound to produce a sonic account for every 20th century decade. Unearthing each decade’s particular sound patterns—its themes, politics, anxieties, recurring notes—DECADES asks: What sounds does a decade make? What is each decade’s mood and tone? Why do sounds repeat and return? What do the sounds we hear tell us about what we are seeing, what we have seen, and what we expect to see in the future? Finally, what new narratives emerge if we use sound as our organizing principle for images rather than the other way around?

What we are seeing now cannot be evaluated in terms of years, arcs, or clear patterns. The 21st century is presentist, formless, anti-ontology, and structurally incoherent. Time—exchanged for the predatory algorithm—is no longer countable. One way I tried to show this in DECADES: 80s (the second installment in my DECADE series; the first was the 1970s) was by creating an hour-long section on sunrises and sunsets. The allegory of daybreak and nightfall is to me an extremely important and moving phenomenology. The section arrives after an hour in the subterranean worlds of the 80s club scene, which always opens its doors onto a daybreak that is both literal and symbolic. The sunrise/sunset cycle is an homage to a lost phenomenology of beginnings and endings. A cycle that—in the case of New York City—is often bookended by the uncanny vista of the Twin Towers—a late 20th century urban lodestar.

In the movies of the 1980s, daybreak offers relief from political and existential horror—a darkness that is literal and metaphorical; pleasurable and nightmarish—while nightfall entails the coming of terror and struggle. A dark night of the soul. The sunrise/sunset sequence is a circadian motif as well as a tautology of obsession and compulsion. It repeats over and over again. Sunrise is an opportunity for the nocturnal, underground addict to begin anew. This diurnal taxonomy is both cinematic and teleological.

In a decade hell-bent on unprecedented greed and materialism, the sunrise/sunset succession is an uncanny structure and occult passageway. Almost every American 80s movie, however slick and oblivious, is imbued with these orphic currents. Movies as varied as Possession (1981), Near Dark (1987) and Die Hard (1988) follow a daybreak/nightfall structure. In retrospect, one could say these movie characters come out alive because a material world still exists to fight for and yet their survival defies all odds (I have always referred to the 1980s as the decade of nine lives because despite—or in spite of—AIDS, in American action movies, at least, the protagonist never dies. The 90s would come to be the end of the myth of invincibility). The algorithm’s invisible typography, which has replaced the phenomenology of time, has eliminated chronotopes, and with it, “emotional valences and spatiality within the films of today,” as a film critic friend put it.

In the 80s, night and day open like portals—something Netflix’s Stranger Things (2017) and Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001), both of which mine the American horrors of the 1980s, make use of. In some sense, this kind of taxonomy does away with genre completely. Regardless of genre, the 70s, 80s, and 90s were full of movies about spirits in the modern world—what Victoria Nelson in The Secret Life of Puppets describes as the deep but hidden attraction the supernatural still holds for a secular mainstream culture. In movies from these decades, pre-gentrificd cities were full of mystery and possibility. “Cleaning them up” has completely eradicated these sacred channels. Similarly, in Tokya-Ga (1985), Wim Wenders observes, “In our century there were still sacred things.” What is interesting about even the most hollow 80s movie is the sacred dualism that runs through nearly every film. As the 1986 movie Highlander puts it: "When only a few of us are left, we will feel an irresistible pull towards a faraway land." I think of 20th century cinema as one such faraway land and DECADES as an attempt to travel to it by simultaneously ascertaining and describing its once-distinct and sensuous motifs.

These motifs depend deeply upon generative polarities that no longer exist.

In the 1980s, we still believed in imminence. Writing about F.W. Marnau’s Nosferatu (which Werner Herzog remade in 1979) in Cinema, Alain Badiou notes: “Overexposure of the meadows, panicking horses, thunderous cuts, together unfold the Idea of a touch of imminence. Of an anticipated visitation of the day by the night.” Time of day, and change in light—simultaneously hopeful and uncanny—meant an end to a certain kind of nightmare reality but also signifies the erosion of its borders. In “Nights,” Frank Ocean sings “Every night fucks every day up/every day patches the night up.” In Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein muses: “Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable.” This sacred pink appears—in Reba McClane’s pink cardigan; in the sky—as a morning rose at the very end of Michael’s Mann’s Manhunter (1986). It envelopes and heals the long awful night of the film.

2019, 6 hours, 19 minutes

In the 20th century, every decade had its own themes, colors, tones, moods, and sounds. A decade (from the Greek déka—δέκα—meaning "ten") is a 20th century phenomenology and bracket of time. Prior to cinema and television, it was perhaps centuries that mattered.

Today neither centuries nor decades exist, which means we have lost time. A way of looking at, remembering, measuring, and understanding both the world and our lives.

In retrospect, it seems clear from the vantage point of the 21st century that 20th century cinema is both verité and spectral because it is a record of all the things that no longer exist. More precisely, it is a testament to what has been destroyed: cities, ways of living, daily rhythms, social fabrics, attention. To watch old movies—the 21st century makes everything look “old”—is to encounter a lost world.

Like my earlier film LOVE SOUNDS (2015), DECADES is a technology produced and circulated by other technologies. Using the found material of film scores and diegetic sound to build a unique soundtrack for an entire decade, DECADES, an ongoing durational series, is a portrait of time. It proposes that the way we experienced cultural shifts in the 20th century was not simply visual or narrative, but tonal. Like LOVE SOUNDS, a 24-hour film which used audio (dialogue) from movies to compose a spoken history of love in English-speaking cinema, DECADES utilizes film score and film sound to produce a sonic account for every 20th century decade. Unearthing each decade’s particular sound patterns—its themes, politics, anxieties, recurring notes—DECADES asks: What sounds does a decade make? What is each decade’s mood and tone? Why do sounds repeat and return? What do the sounds we hear tell us about what we are seeing, what we have seen, and what we expect to see in the future? Finally, what new narratives emerge if we use sound as our organizing principle for images rather than the other way around?

What we are seeing now cannot be evaluated in terms of years, arcs, or clear patterns. The 21st century is presentist, formless, anti-ontology, and structurally incoherent. Time—exchanged for the predatory algorithm—is no longer countable. One way I tried to show this in DECADES: 80s (the second installment in my DECADE series; the first was the 1970s) was by creating an hour-long section on sunrises and sunsets. The allegory of daybreak and nightfall is to me an extremely important and moving phenomenology. The section arrives after an hour in the subterranean worlds of the 80s club scene, which always opens its doors onto a daybreak that is both literal and symbolic. The sunrise/sunset cycle is an homage to a lost phenomenology of beginnings and endings. A cycle that—in the case of New York City—is often bookended by the uncanny vista of the Twin Towers—a late 20th century urban lodestar.

In the movies of the 1980s, daybreak offers relief from political and existential horror—a darkness that is literal and metaphorical; pleasurable and nightmarish—while nightfall entails the coming of terror and struggle. A dark night of the soul. The sunrise/sunset sequence is a circadian motif as well as a tautology of obsession and compulsion. It repeats over and over again. Sunrise is an opportunity for the nocturnal, underground addict to begin anew. This diurnal taxonomy is both cinematic and teleological.

In a decade hell-bent on unprecedented greed and materialism, the sunrise/sunset succession is an uncanny structure and occult passageway. Almost every American 80s movie, however slick and oblivious, is imbued with these orphic currents. Movies as varied as Possession (1981), Near Dark (1987) and Die Hard (1988) follow a daybreak/nightfall structure. In retrospect, one could say these movie characters come out alive because a material world still exists to fight for and yet their survival defies all odds (I have always referred to the 1980s as the decade of nine lives because despite—or in spite of—AIDS, in American action movies, at least, the protagonist never dies. The 90s would come to be the end of the myth of invincibility). The algorithm’s invisible typography, which has replaced the phenomenology of time, has eliminated chronotopes, and with it, “emotional valences and spatiality within the films of today,” as a film critic friend put it.

In the 80s, night and day open like portals—something Netflix’s Stranger Things (2017) and Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001), both of which mine the American horrors of the 1980s, make use of. In some sense, this kind of taxonomy does away with genre completely. Regardless of genre, the 70s, 80s, and 90s were full of movies about spirits in the modern world—what Victoria Nelson in The Secret Life of Puppets describes as the deep but hidden attraction the supernatural still holds for a secular mainstream culture. In movies from these decades, pre-gentrificd cities were full of mystery and possibility. “Cleaning them up” has completely eradicated these sacred channels. Similarly, in Tokya-Ga (1985), Wim Wenders observes, “In our century there were still sacred things.” What is interesting about even the most hollow 80s movie is the sacred dualism that runs through nearly every film. As the 1986 movie Highlander puts it: "When only a few of us are left, we will feel an irresistible pull towards a faraway land." I think of 20th century cinema as one such faraway land and DECADES as an attempt to travel to it by simultaneously ascertaining and describing its once-distinct and sensuous motifs.

These motifs depend deeply upon generative polarities that no longer exist.

In the 1980s, we still believed in imminence. Writing about F.W. Marnau’s Nosferatu (which Werner Herzog remade in 1979) in Cinema, Alain Badiou notes: “Overexposure of the meadows, panicking horses, thunderous cuts, together unfold the Idea of a touch of imminence. Of an anticipated visitation of the day by the night.” Time of day, and change in light—simultaneously hopeful and uncanny—meant an end to a certain kind of nightmare reality but also signifies the erosion of its borders. In “Nights,” Frank Ocean sings “Every night fucks every day up/every day patches the night up.” In Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein muses: “Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable.” This sacred pink appears—in Reba McClane’s pink cardigan; in the sky—as a morning rose at the very end of Michael’s Mann’s Manhunter (1986). It envelopes and heals the long awful night of the film.

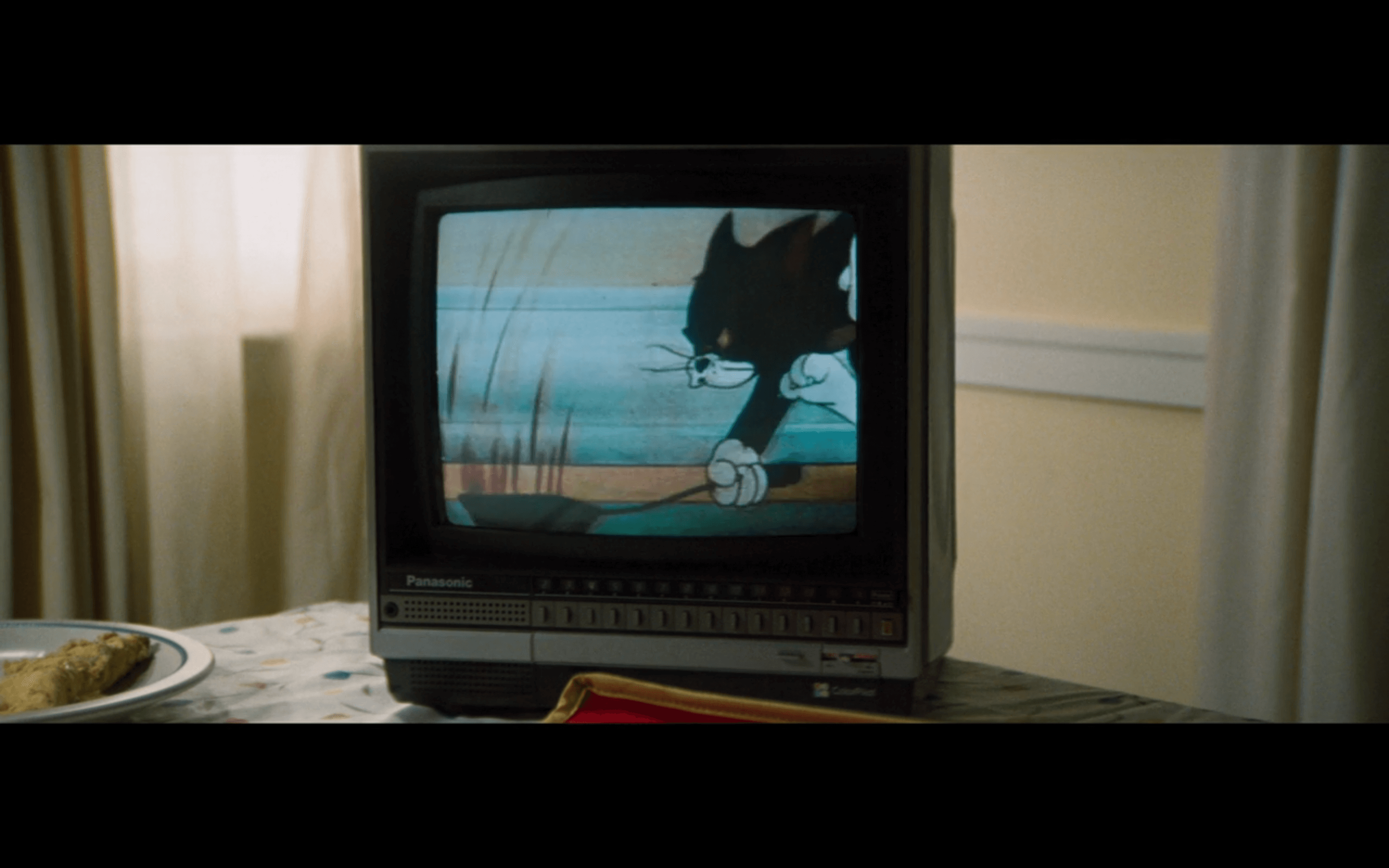

In DECADES: 80s, the sunrise/sunset trope eventually evolves into other cinematic ontologies and chronotopes, like body horror and the home-invasion of televisions and computers, excerpted for this issue. Despite these intimate encounters and convergences with technology, 70s and 80s horror was a body experience, not a machine experience. Likewise, cinema itself was a tactile material, a celluloid dependent on the miracle of real light.

In the 70s and 80s, supercomputers control the world and big-tech technology is kryptonite not just for Superman in the movie franchise’s fourth sequel (1987), but for the entire human race. Computers were seen as malignant and mysterious encroachments upon human life, as was the government and law enforcement—a distrust that was firmly established in the 1970s—launched by Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Ironically, the guys (the Spielberg boys) that became the first computer programmers in Silicon Valley were the ones who grew up on these paranoid anti-computer parables.

The world we live in now was born in the 1980s. Yet decades don't always arrive on time.

In the 70s and 80s, supercomputers control the world and big-tech technology is kryptonite not just for Superman in the movie franchise’s fourth sequel (1987), but for the entire human race. Computers were seen as malignant and mysterious encroachments upon human life, as was the government and law enforcement—a distrust that was firmly established in the 1970s—launched by Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Ironically, the guys (the Spielberg boys) that became the first computer programmers in Silicon Valley were the ones who grew up on these paranoid anti-computer parables.

The world we live in now was born in the 1980s. Yet decades don't always arrive on time.

All pre-internet horror was tactile and acoustic, involving both eye and ear. The TV/body horror/technology section (which follows the sunrise/sunset sequence) mines the ontology of 80s horror, which also transcends the genre. It articulates what I see as the decade’s zeitgeist motifs and sounds by identifying their emotional resonances as psychogeography. Decade as shape, decade as sacred geometry, decade as score, decade as sieve, decade as hopes, wishes, and dreams, decade as lattice of coincidences. As such, DECADES is concerned with the work of listening to cinema. The ongoing series is an attempt to restage encounters with time. The time of cinema. I believe durational formats are essential to both reclaiming and remembering time.

The TV/body horror/technology section in DECADES is composed and arranged like channels flipping on a CRT television, which took the incoming signal and broke it into its separate audio (sound) and video (picture) components. Old-style TVs were radios with pictures. The VCR boom altered not only our relation to spectacle and image, but the temporality and spatialty of spectacle and image, making us fetishistic spectators rather than pensive spectators, as Laura Mulvey argues. Steven Spielberg’s 80s cinema shows us this, but so do the early films of Michael’s Haneke (see The Seventh Continent and Benny’s Video) and Wim Wenders, who in his search for Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo in 1984, found a city full of screens instead: “It’s a made for TV world. Every shitty television set, no matter where, is the center of the world.”

The TV/body horror/technology section in DECADES is composed and arranged like channels flipping on a CRT television, which took the incoming signal and broke it into its separate audio (sound) and video (picture) components. Old-style TVs were radios with pictures. The VCR boom altered not only our relation to spectacle and image, but the temporality and spatialty of spectacle and image, making us fetishistic spectators rather than pensive spectators, as Laura Mulvey argues. Steven Spielberg’s 80s cinema shows us this, but so do the early films of Michael’s Haneke (see The Seventh Continent and Benny’s Video) and Wim Wenders, who in his search for Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo in 1984, found a city full of screens instead: “It’s a made for TV world. Every shitty television set, no matter where, is the center of the world.”

Eventually, with the internet, we even lost the sound of the channel changing. Today the image has no schedule, no double, no frame. It no longer shuts off. It has no end point or pause. Spectatorship is continuous and constant. As a cinematic trope, the disjuncture and allegorical fusion between the language of cinema and the language of TV in the 1980s also symbolizes the imminent totality of technology.

In the 1980s, TV splits the screen of cinema in half. Cinema haunts TV and vice versa. The mise-en-scène is frequently organized around the extra-diegetic presence of TV sets which, like the iPhone, are never really off and tell us something about the world that movies don’t. A TV that is left on all night while the young characters sleep in Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and Poltergeist (1982) is a gateway for possession and death. In Videodrome (1983) and Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), TV transmissions emit secret signals that produce brain tumors and hallucinations in its viewers. In Videodrome, James Woods stomach turns into a VCR. His body becomes a VHS tape he can inject into the TV-mouth of a woman. In Weird Science (1985), a reimagination of the Frankenstein parable, male pornographic fantasies come to life, as two geeky teenage American boys program then download the perfect woman into existence. The TV/body horror/technology section is about possessions and mutations that are mediated and engineered by technology, yet cannot be explained by it.

For the first time in history, everyday people are alone in their rooms with computers and televisions. These private encounters lead to strange and unforeseen things. Horrors, deaths, possessions, escapes, fantasies. TV sets are secret portals. The small screen is not only woven into the domestic space and diegesis of the movie screen, it is, as so many films from the period show, a kind of white noise that leeches into our dreams. Movies from the 1940s and 50s—Hammer Horror, sci-fi B movies, and American Westerns; films many 80s directors grew up with—play on TV. These TV images and sounds are both primary and peripheral, vacillating between onscreen and offscreen. Everyday objects become paranormal. Their electronic wiring is monstrous and secretly rigged. After the 1980s, and the birth of MTV in every home (except mine somehow), it is important to ask to what medium—or realm—do these cultural sounds, images, and events belong?

Colson Whitehead remembers the VCR boom that presided over every 80s American childhood: “We acquired our first VCR, and laissez-faire parenting combined with the home-video boom to nudge me into my next incarnation: I had been a shut-in; now I was a latchkey cineaste…My brother and I dropped the stack of Betamax tapes on the coffee table and got to work, two or three movies on Friday night, the rest on Saturday. Once we’d adjusted the tracking on the VCR (the tracking, always the tracking).”

The reign of TV that infiltrated American culture in the 1980s (in the 1950s the TV was still a family set piece) via the cinematic imaginary is an important chronotope. TV was the primary parent to the solitary latchkey kid, who was now directly occupied, enthralled, possessed, or deranged by the gestalt (or as Whitehead refers to it, the tracking) of mass media. Even a true crime art film like James Benning’s 1987 Landscape Suicide feels haunted by the predatory rise of popular culture. In it, the pop music that blares inside the suburban bedrooms of teenagers is heard from outside the houses, which Benning films in static wide shots. The long shots give the illusion of pastoral calm. The music—in this case Michael Jackson’s “P.Y.T.” (the acronym itself makes the song title a kind of menacing code)—is almost a Peeping Tom. An ominous acousmatic presence that drowns out and scores—both in life and on screen—crimes that are committed all around us every day. Somehow hearing the music that is playing inside the house outside the house conveys the eerie power of intangible encroachment. All landscapes are crime scenes, Benning says. In Suicide, the image conceals while the audio track makes us see and feel things that are not visible to the eye. Benning’s laconic approach to true crime is experimental but his heavy, auditory cuts are procedural.

In the 1980s, TV splits the screen of cinema in half. Cinema haunts TV and vice versa. The mise-en-scène is frequently organized around the extra-diegetic presence of TV sets which, like the iPhone, are never really off and tell us something about the world that movies don’t. A TV that is left on all night while the young characters sleep in Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and Poltergeist (1982) is a gateway for possession and death. In Videodrome (1983) and Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), TV transmissions emit secret signals that produce brain tumors and hallucinations in its viewers. In Videodrome, James Woods stomach turns into a VCR. His body becomes a VHS tape he can inject into the TV-mouth of a woman. In Weird Science (1985), a reimagination of the Frankenstein parable, male pornographic fantasies come to life, as two geeky teenage American boys program then download the perfect woman into existence. The TV/body horror/technology section is about possessions and mutations that are mediated and engineered by technology, yet cannot be explained by it.

For the first time in history, everyday people are alone in their rooms with computers and televisions. These private encounters lead to strange and unforeseen things. Horrors, deaths, possessions, escapes, fantasies. TV sets are secret portals. The small screen is not only woven into the domestic space and diegesis of the movie screen, it is, as so many films from the period show, a kind of white noise that leeches into our dreams. Movies from the 1940s and 50s—Hammer Horror, sci-fi B movies, and American Westerns; films many 80s directors grew up with—play on TV. These TV images and sounds are both primary and peripheral, vacillating between onscreen and offscreen. Everyday objects become paranormal. Their electronic wiring is monstrous and secretly rigged. After the 1980s, and the birth of MTV in every home (except mine somehow), it is important to ask to what medium—or realm—do these cultural sounds, images, and events belong?

Colson Whitehead remembers the VCR boom that presided over every 80s American childhood: “We acquired our first VCR, and laissez-faire parenting combined with the home-video boom to nudge me into my next incarnation: I had been a shut-in; now I was a latchkey cineaste…My brother and I dropped the stack of Betamax tapes on the coffee table and got to work, two or three movies on Friday night, the rest on Saturday. Once we’d adjusted the tracking on the VCR (the tracking, always the tracking).”

The reign of TV that infiltrated American culture in the 1980s (in the 1950s the TV was still a family set piece) via the cinematic imaginary is an important chronotope. TV was the primary parent to the solitary latchkey kid, who was now directly occupied, enthralled, possessed, or deranged by the gestalt (or as Whitehead refers to it, the tracking) of mass media. Even a true crime art film like James Benning’s 1987 Landscape Suicide feels haunted by the predatory rise of popular culture. In it, the pop music that blares inside the suburban bedrooms of teenagers is heard from outside the houses, which Benning films in static wide shots. The long shots give the illusion of pastoral calm. The music—in this case Michael Jackson’s “P.Y.T.” (the acronym itself makes the song title a kind of menacing code)—is almost a Peeping Tom. An ominous acousmatic presence that drowns out and scores—both in life and on screen—crimes that are committed all around us every day. Somehow hearing the music that is playing inside the house outside the house conveys the eerie power of intangible encroachment. All landscapes are crime scenes, Benning says. In Suicide, the image conceals while the audio track makes us see and feel things that are not visible to the eye. Benning’s laconic approach to true crime is experimental but his heavy, auditory cuts are procedural.

In the 1980s technology was still an Other. Unlike the cinematic sub-trope of TV, 21st century cinema, with the exception of a handful of examples like Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void (2009) and Oliver Assayas’ Personal Shopper (2016), does not engage with or make use of smartphones in the same way. Unlike life, which is now ruled by smart devices and digital algorithms, the smartphone is largely missing from the cinematic imaginary because smartphones have no real visual or connotative charge. As in life, it is quite simply boring and alienating to look at someone on their cell phone. By centralizing the presence of technology in our everyday life, we have expunged all of its uncanny and psychic affects (or even what it means philosophically to receive or make a call) by completely eradicating its shadow side. Life is technology now, but cinema was always fundamentally subjunctive and transportive. There may not be what is called human without technology, but if there is nothing but technology, there is no human. And probably no cinema either (only streaming TV, which tellingly, has a lot of smartphones). Unlike the 2000s, the 1980s understood this.

MASHA TUPITSYN is a writer, critic, and multi-media artist. She is the author several films and books, most recently Picture Cycle (Semiotexte/MIT, 2019). The first part of her 3-volume book series, TIME TELLS, is forthcoming with Archway Editions/Simon & Schuster in 2022. Her website is: www.mashatupitsyn.com

MASHA TUPITSYN is a writer, critic, and multi-media artist. She is the author several films and books, most recently Picture Cycle (Semiotexte/MIT, 2019). The first part of her 3-volume book series, TIME TELLS, is forthcoming with Archway Editions/Simon & Schuster in 2022. Her website is: www.mashatupitsyn.com