Maggie Hennefeld

Hysteria, Hypnosis, and Hallucination

in the Archives of Silent Cinema

In 1911, an Italian woman suffered horrific hallucinations that haunted her every night while she slept after watching a crime film in which a railway clerk dreams that he’s being attacked by thieves—only to awaken to that very reality! At first, she only saw the hallucinations at night: “the vision of GIGANTIC HANDS in extraordinary number,” but soon they began to appear all the time, “so suddenly and in the most unexpected situations.” Even though she was “perfectly aware of [their] unreality,” remarked her psychiatrist, “she still ended up being very disturbed.” The apparitions persisted and intensified in their multi-sensory dimensions to the point that they became tactile, as she felt the hands grabbing and touching her out of thin air.

Images of hypnosis, hallucination, and hysteria provided irresistible material for early silent filmmakers. In Chez le magnétiseur [At the Hypnotist’s], a trick film from 1897 made by the prolific director Alice Guy-Blaché, a woman visits the hypnotist where she is mesmerized, undressed, and forced to switch clothes with a soldier. All of this happens in a flash, provoking a profound sense of confusion between film illusion and hypnotic hallucination. Do the transformations we witness represent the inner experience of a hypnotized woman? Or is the film’s premise a mere canvas for displaying rapid alterations in gender, clothing, social identity, and bodily appearance? Only viewers already vulnerable to hypnosis—hysterics, somnambulists, insomniacs, neurotics—would fall prey to the medium’s overly vivid impression of reality. But who among us isn’t susceptible to hypnosis in the presence of cinema?

For the spooky season this year, I curated a program of silent films screening at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities on Hysteria, Hypnosis, Hallucination, and Cinema’s First Nasty Women. The event took place with live musical accompaniment, featuring the local band Dreamland Faces who brought their repertoire of piano accordions and musical saws in concert with a newly refurbished, silent film-era organ. The screening was followed by a panel including a feminist rhetorician (Emily Winderman), an art curator who specializes in the history of American Spiritualism (Robert Cozzolino), a Victorian medium-impersonator (Michael Callahan), and Dreamland Faces composer, Karen Majewicz. This in-person event was livestreamed and will be archived on-demand through October 31—in anticipation of the forthcoming DVD/Blu-ray collection, Cinema’s First Nasty Women.

For the spooky season this year, I curated a program of silent films screening at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities on Hysteria, Hypnosis, Hallucination, and Cinema’s First Nasty Women. The event took place with live musical accompaniment, featuring the local band Dreamland Faces who brought their repertoire of piano accordions and musical saws in concert with a newly refurbished, silent film-era organ. The screening was followed by a panel including a feminist rhetorician (Emily Winderman), an art curator who specializes in the history of American Spiritualism (Robert Cozzolino), a Victorian medium-impersonator (Michael Callahan), and Dreamland Faces composer, Karen Majewicz. This in-person event was livestreamed and will be archived on-demand through October 31—in anticipation of the forthcoming DVD/Blu-ray collection, Cinema’s First Nasty Women.

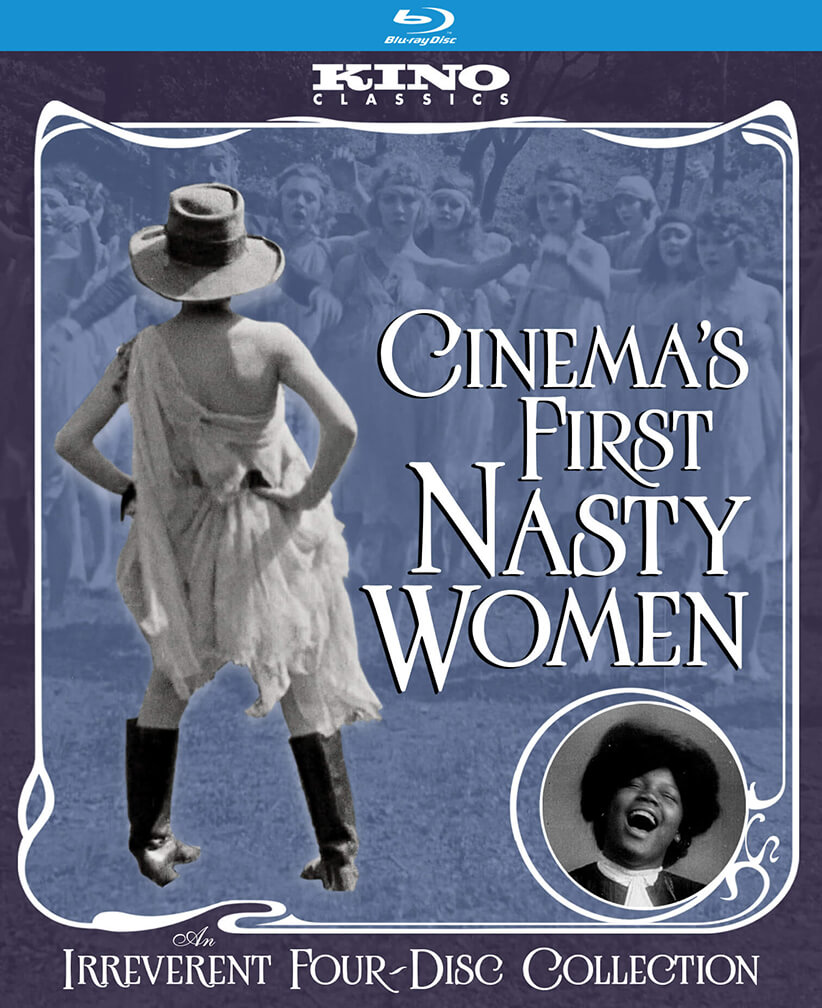

The six silent films in the program give voice to dueling perceptions of early cinema as a gateway to radical social change and as a dangerous technology that will surely drive everyone mad! Viewers behold: “a woman is hypnotized by a Svengali, a jealous lover practices tele-hypnosis to defeat his rival, an overworked housemaid has sleeping sickness, a female coach driver can’t believe her eyes, an obsessive inventor gives us a sneak preview of Zoom, and cinematography offers a miraculous cure to hysterical amnesia.” Characters in these films are tormented by various forms of hysteria, hypnosis, and hallucination. In Cunégonde femme cochère [Cunégonde the Coachwoman] (1913), a female coach driver (played by the legendary Little Chrysia) runs over a fakir who curses her with a series of bizarre mental images: she sees her horse turn into a zebra, her carriage into a cupboard, and her own passenger into a bear who then tries to assault her. As in Guy-Blaché’s Chez le magnétiseur, the spectator marvels at these surreal transfigurations, but it remains unclear whether they represent objective feats of occult magic or if they were all in someone else’s head. Cunégonde’s curse paves the way to the spectators’ collective hypnosis!

Hypnotizing the Hypnotist (1911) is an especially interesting example. The plot is simple: the scorned lover of a woman seduced by a charlatan hypnotist steals a professional hypnotist’s manual in tele-hypnosis (“How to Hypnotize from a Distance”), which he then uses to liberate his sweetie from the clutches of a sham mesmerist. The woman is played by Florence Turner, one of America’s first movie stars (a.k.a. “The Vitagraph Girl”) who was herself a talented filmmaker, writer, producer, and stage impersonator. Famous for her facial mimicry, Turner steals the show, embracing the pageantry of hypnosis as a vehicle for her outsized theatrical energies. She dances around, flails her limb, and makes grotesque faces at the hypnotist. Her maid (played by the great Kate Price) hops around like a bunny and then throws the Svengali out on his ass. The farce of male hypnotist rivalry is just a springboard for the jouissance of women behaving outrageously and having a good time. “There’s hardly an inch that isn’t funny,” declared The Moving Picture World (referring to the length of the reel).

Make light if you will, but it was “a time when novels, plays, and films—not to mention medical and legal discourse—debated whether one person could control the spirit, soul, or mind of another at a distance,” muses Jennifer Bean in her audio commentary for this film in Cinema’s First Nasty Women. And what is cinema if not a dark art of tele-hypnosis, of hypnotizing from a distance? Over 100 years later, many of us are still under early cinema’s spell. 80% of all silent films are now irretrievably lost, but new treasures are being unearthed every day. They transform our historical memory of how the medium was initially cultivated to change minds and capture souls.

Hypnotizing the Hypnotist was far from the only hypnosis-themed, feminist comedy of 1911. There was also Hypnotizing a Hypnotist, a lost film in which a landlady (played by Dott Farley) at an asylum tyrannized by an abusive mesmerist steals his hypnosis manual and marries him against his will while he’s under the spell of a hypnotic trance. The Moving Picture News hailed Hypnotizing a Hypnotist as “fast and furious…undoubtedly as funny a farce comedy as the most discriminating hypnotist could desire.” If comedy places vulnerable feelings at a distance—“a momentary anesthesia of the heart,” as Henri Bergson put it in 1900—slapstick cinema exploited tele-hypnosis as an immediate danger of popular psychology unleashed by mass commercial culture.

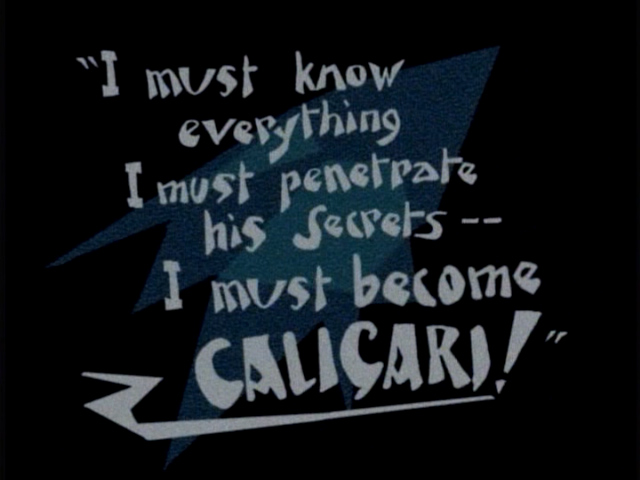

“I must know everything. I must penetrate his secrets—I must become CALIGARI!” A metaphor for mob somnambulism and for cinema itself in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), film’s hypnotic powers could swing either way–towards jubilant liberation or fascist domination. Hypnosis was widely feared in its capacity to exercise autocratic control over an individual’s conscious will. But early films rallied the spectacle of hypnosis toward precisely the opposite end: stirring the people’s imagination to rebel against their social position and given historical conditions.

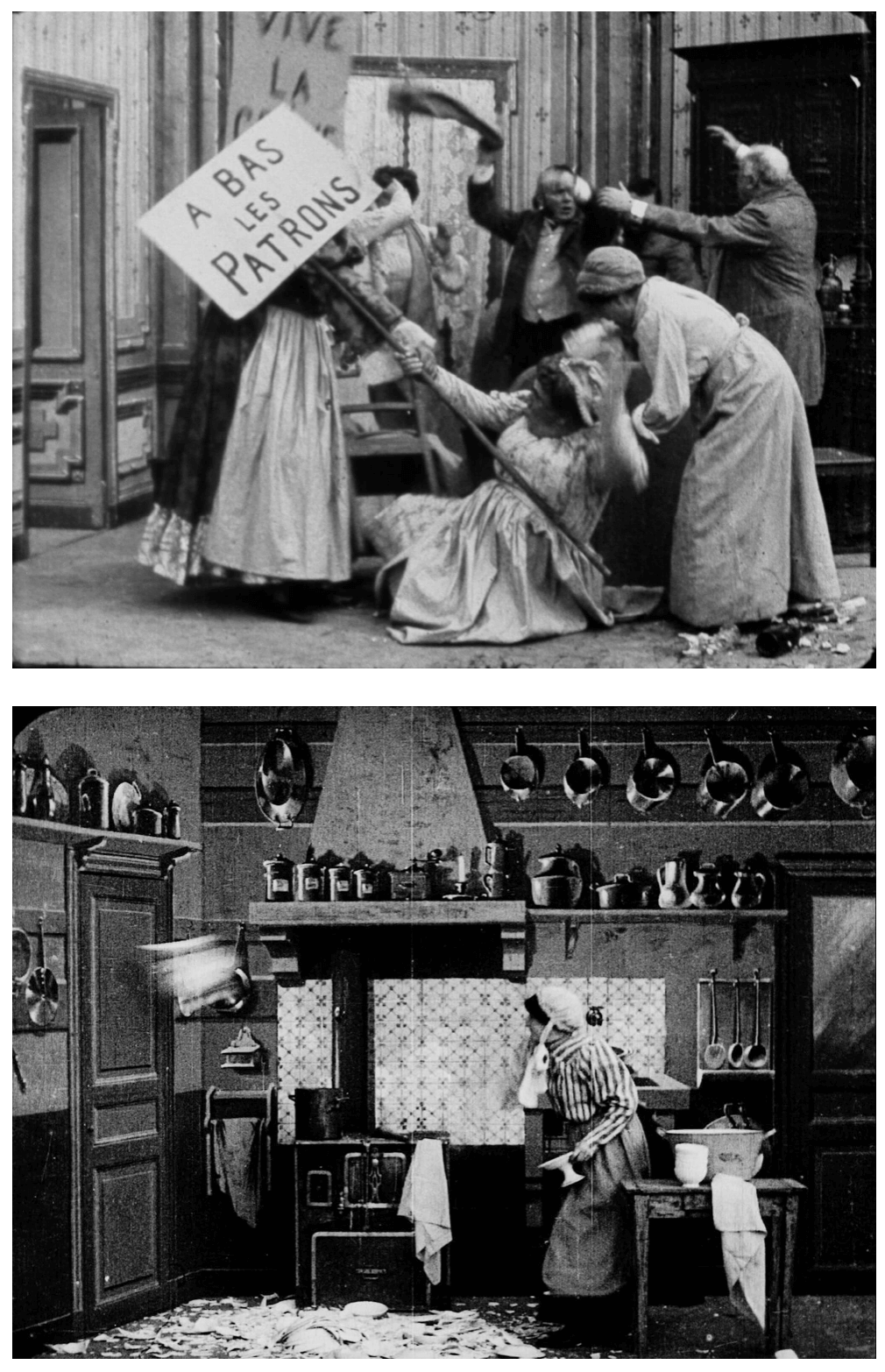

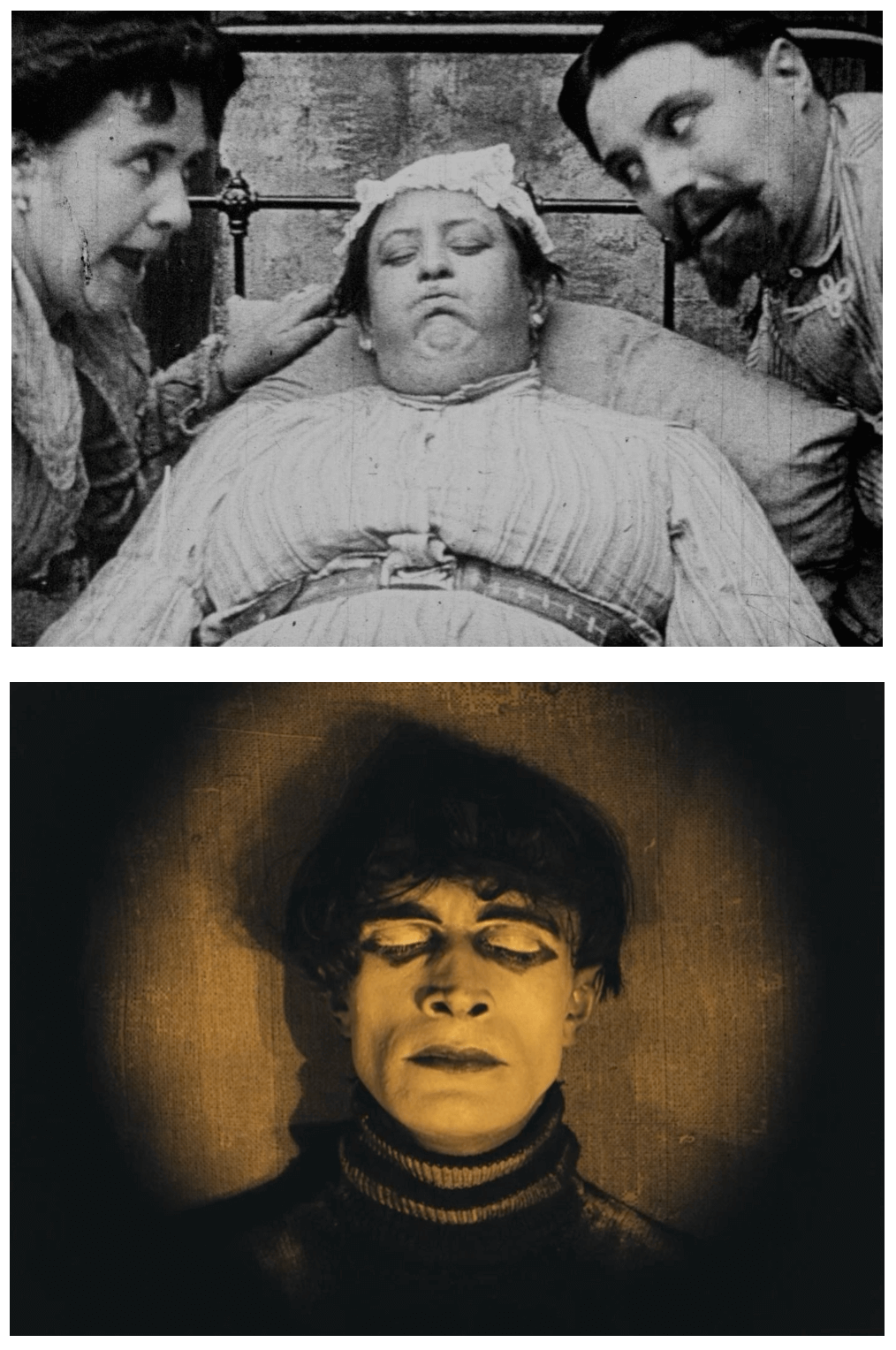

Rosalie a la maladie du sommeil [Rosalie Has Sleeping Sickness] (1911) exemplifies that electricity between the sight gag of hysteria and glimmers of social defiance. Played by the great stage and screen comedienne Sarah Duhamel, Rosalie is an overworked housemaid who suffers from hysterical “sleeping sickness.” Her body language and gestures are larger than life, which is a fascinating way to pantomime her character’s exhaustion and physical lethargy. Rosalie’s yawns fill the frame as she nearly spills hot food all over her employers, who send her to bed in hopes she will be ready to resume work after just a quick nap. (She will not! No amount of noise or abuse can make her go back to work.) In contrast, Caligari’s nightmare of somnambulism imagines a more sinister fate for the bodies that sleepwalk through their ordinary waking life. Recalcitrant kitchen maid or pawn in mass murder?

Rosalie a la maladie du sommeil [Rosalie Has Sleeping Sickness] (1911) exemplifies that electricity between the sight gag of hysteria and glimmers of social defiance. Played by the great stage and screen comedienne Sarah Duhamel, Rosalie is an overworked housemaid who suffers from hysterical “sleeping sickness.” Her body language and gestures are larger than life, which is a fascinating way to pantomime her character’s exhaustion and physical lethargy. Rosalie’s yawns fill the frame as she nearly spills hot food all over her employers, who send her to bed in hopes she will be ready to resume work after just a quick nap. (She will not! No amount of noise or abuse can make her go back to work.) In contrast, Caligari’s nightmare of somnambulism imagines a more sinister fate for the bodies that sleepwalk through their ordinary waking life. Recalcitrant kitchen maid or pawn in mass murder?

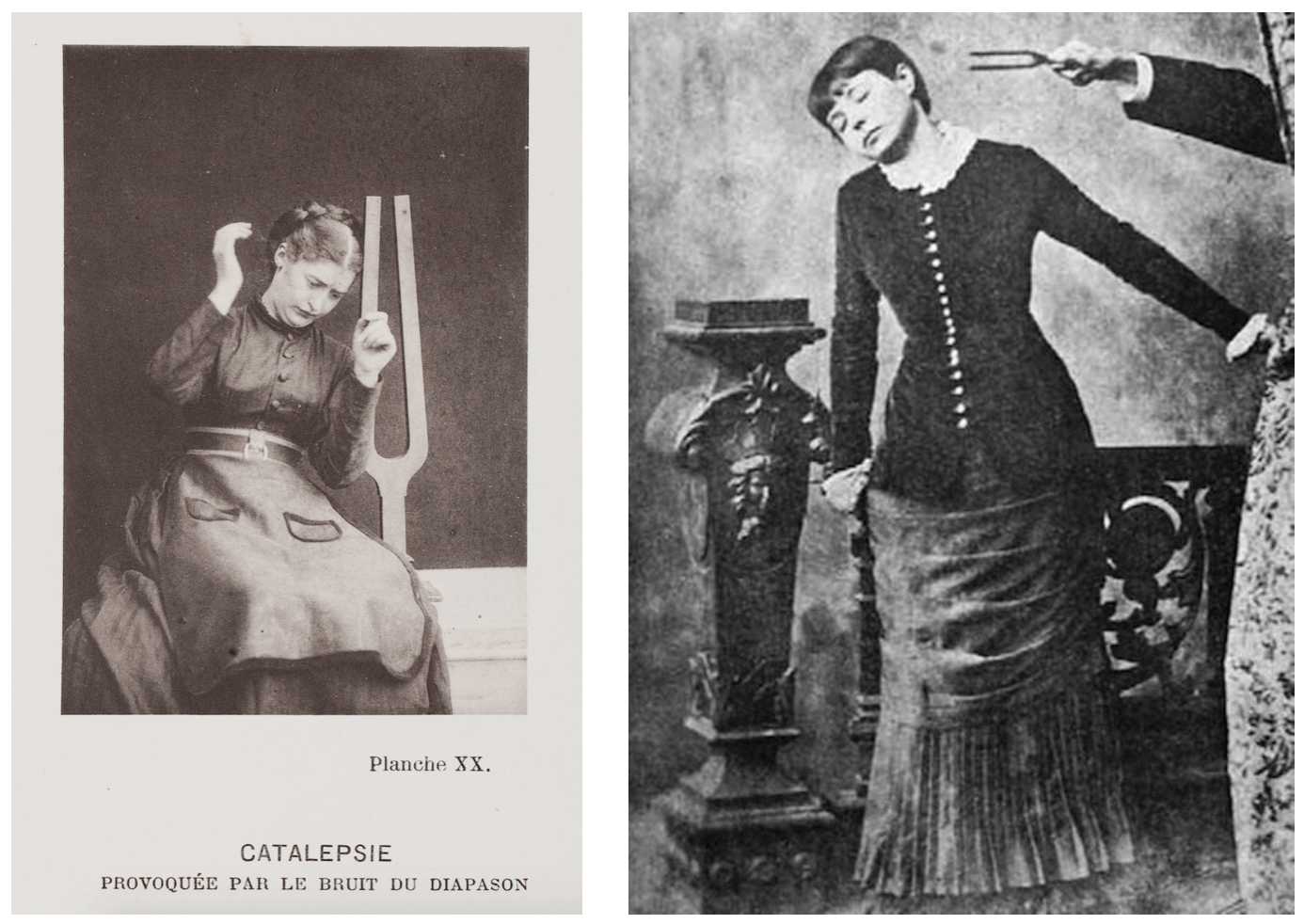

Cinema itself was depicted as both a nervous trigger and infallible cure to the bugaboo of collective hysteria. “The rapid succession of images intensifies the pleasurable tension to an unbearable level,” warned the German anti-film evangelist Robert Graupp, “without giving us the means by which to defend our psyches against these attacks.” Beyond the foibles of comedy—in which women authored their own hypnosis to break free of their stifling social roles—hysteria held an intimate connection to the volatile technologies of cinema in melodramas, crime thrillers, and adventure serials alike. The actress Jean Sothern allegedly underwent hypnosis while filming The Mysteries of Myra, a paranormal serial in which she plays a trance-medium who uses astral projection, spirit conjuring, and ritualistic séances to battle a demonic cult that has condemned her to death. And it was always a slippery slope from hypnosis to hysteria, as the hypnotist ringmaster Jean-Martin Charcot famously argued. In fact, Charcot defined hysteria as the unique susceptibility to hypnosis, which he exploited ruthlessly to study and “treat” his patients’ hystero-epileptic attacks.

Silent films about film as a miraculous cure to the endemic triggers of nervous hysteria are innumerable (and ultimately unknowable due to the losses and erasures of the archive). Cinema itself was even used in American mental institutions as a one-size-fits-all cure to any diagnosis of madness. “The flitting figures that marched before the canvas” could “subdue the chaotic mind” with “quiet fascination,” reported The Nickelodeon in 1910 in an article about “Moving Pictures Curing Insanity.” As a set-up for slapstick comedy, eccentric clowns relieve their mania and depression by going to the movies in titles such as Tontolini Is Sad (1911), Dr. Max In Spite of Himself (1917), and A Representation of Cinema (1910). In a very different vein, the last two films in our program reveal the movie cure’s dangerous entanglement with the madness of its own making.

Amour et science [Love and Science] (1912) and Le mystère des roches de Kador [The Mystery of the Rocks of Kador] (1912) both dramatize the psychiatric powers (and perils!) of how film images flicker between reality and illusion. These films are also all about sexuality and gender. Even though hysteria has its etymology in the wandering uterus (“hystera”) and was widely understood as a “female malady,” it also afflicted men—nervous, shellshocked, or merely passive men whose masculine virility was allegedly weakened by the feminized pleasure garden of mass consumer culture. In Amour et science, a man obsessively invents a new machine for seeing at a distance (also known as “tele-vision,” notes Doron Galili), which he debuts by surveilling his fiancée, who tricks him by pretending to cheat on him with another man, who is actually her female friend in gender-bending disguise. This sexual humiliation gives Max (the inventor) a panic attack: he can only be revived by re-watching the scene of his trauma as a filmic projection. Unlike tele-vision, which hinges on liveness and immediacy, cinema’s time delay (its uncanny conjuring of dead/past moments in the paradoxical form of presence) solidly recommends it as the superior anti-hysterical medium for channeling visual knowledge about both technological change and gender experimentation. “Calling into question the idea that modern media represent direct imprints of reality,” observes Katharina Loew, “Amour et science speaks to fears about losing one’s grip on truth in an increasingly mediated world.” Like hypnosis, cinema intercedes between human will and capitalism’s hall-of-mirrors, as virtual images run roughshod over physical reality and direct experience. Better to be hypnotized by an image of hope than fall prey to regressive nostalgia!

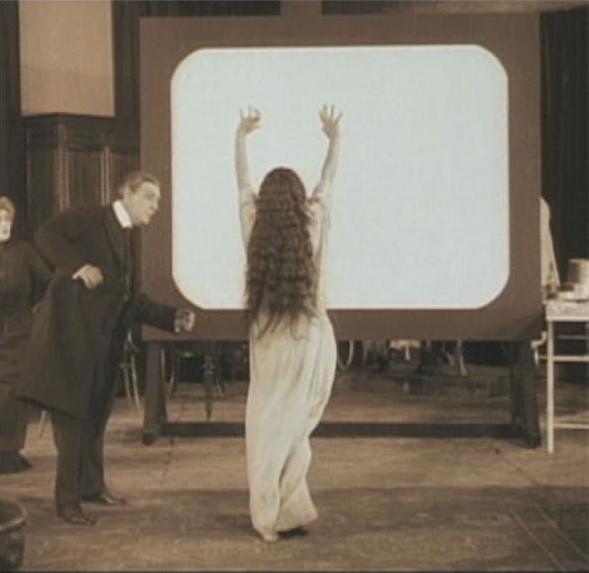

Le mystère des roches de Kador is the most literal and the most complex in its depiction of cinema as an instantaneous cure to nervous hysteria. Released in the US with the title In the Grip of the Vampire, Kador again poses cinema as the perfect antidote to modernity’s dizzying confusion between virtual play and hysterical hallucination. A young woman is tormented by her guardian (played by the filmmaker, Léonce Perret) who stands to claim her rightful inheritance in the event that she goes mad before her eighteenth birthday, which is precisely what happens after witnessing the death of her lover (or so she believes!). Played by Suzanne Grandais (an internationally beloved star known as “The Mary Pickford of France”), Suzanne’s hysterical amnesia is so all-consuming that even a direct encounter with her supposedly deceased lover cannot bring her back to her senses. Enter: Cinema! At the advice of a psychoanalyst, her friends reenact the scene of her trauma and project it before her in a private film theater.

I will leave the rest to your imagination, but hopefully also to the future of your silent film spectatorship. We all owe a debt to the archive. And in the event that you’re haunted by floating, clutching hallucinations of GIGANTIC, DISEMBODIED HANDS this evening before bed, I have just the cure for you!

Maggie Hennefeld is Associate Professor of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature and McKnight Presidential Fellow at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is author of Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (Columbia UP, 2018), an editor of the journal Cultural Critique (UMN Press) and of two volumes: Unwatchable (Rutgers UP, 2019) and Abjection Incorporated: Mediating the Politics of Pleasure and Violence (Duke UP, 2020). She is also a curator of the 4-disc DVD/Blu-ray set, Cinema’s First Nasty Women (Kino Lorber, 2022), which includes 99 archival feminist silent films.