Dodie Bellamy on The Letters of Mina Harker

Interview by Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Thomas: The Letters of Mina Harker, your debut novel from 1998 — now hot off the press in a new edition — opens in the oldest movie theater in San Fransisco, The Roxie, during a screening of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, which I’d like to return to in a little bit. But first I just want to say I was surprised by how many movies you write about in this book!

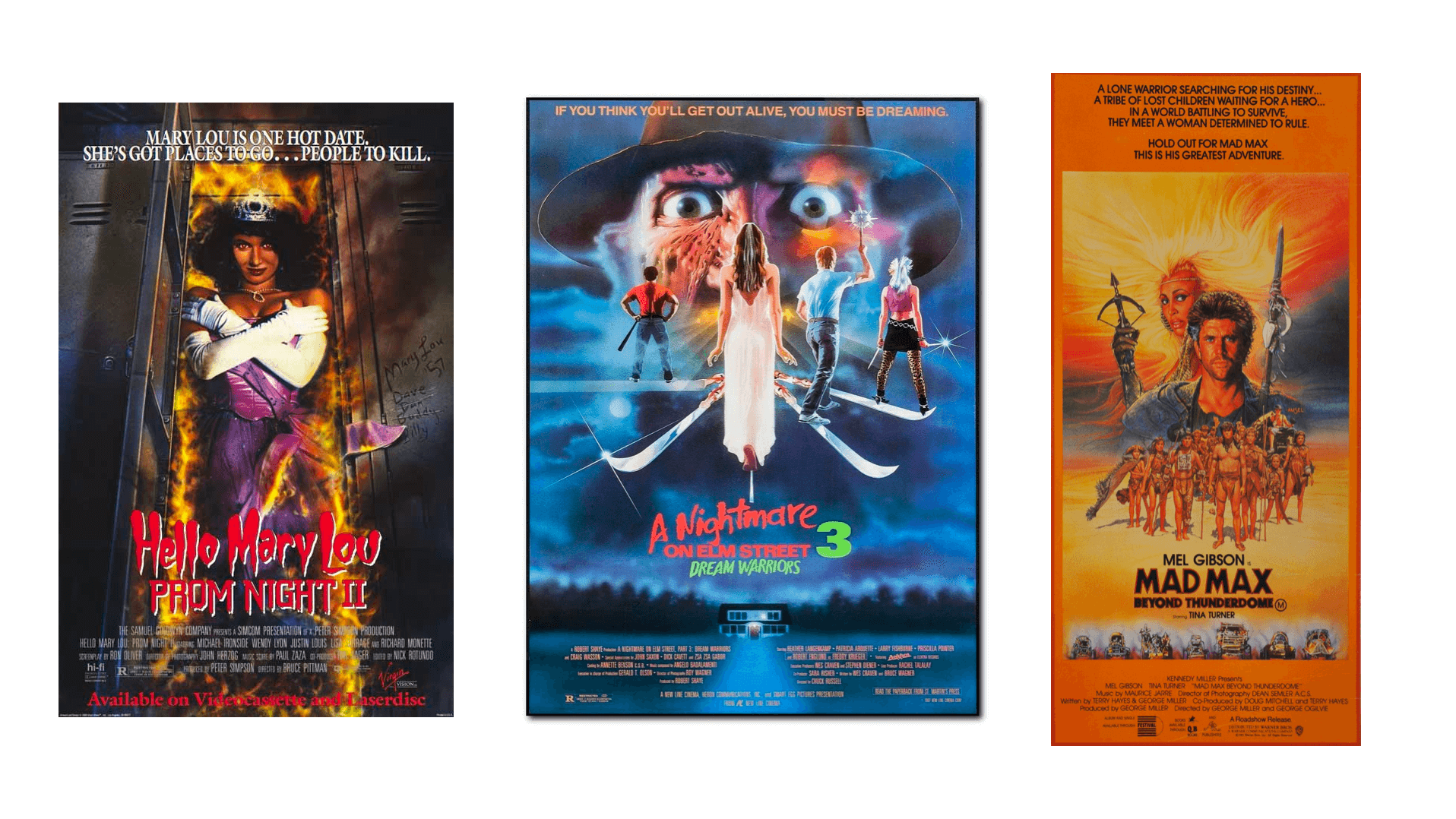

Dodie Bellamy: Well clearly that book is a tribute to all sorts of trash cinema.

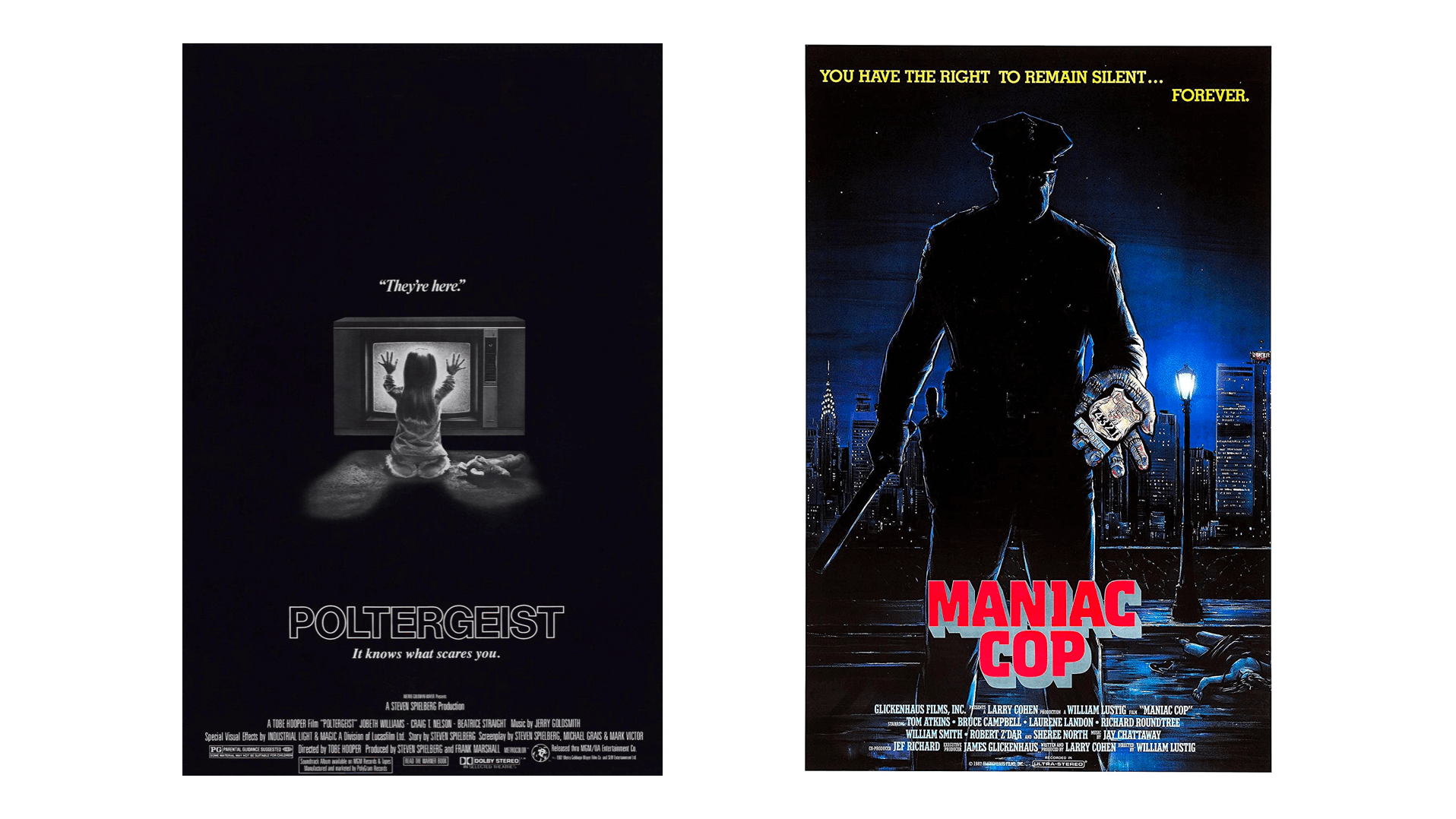

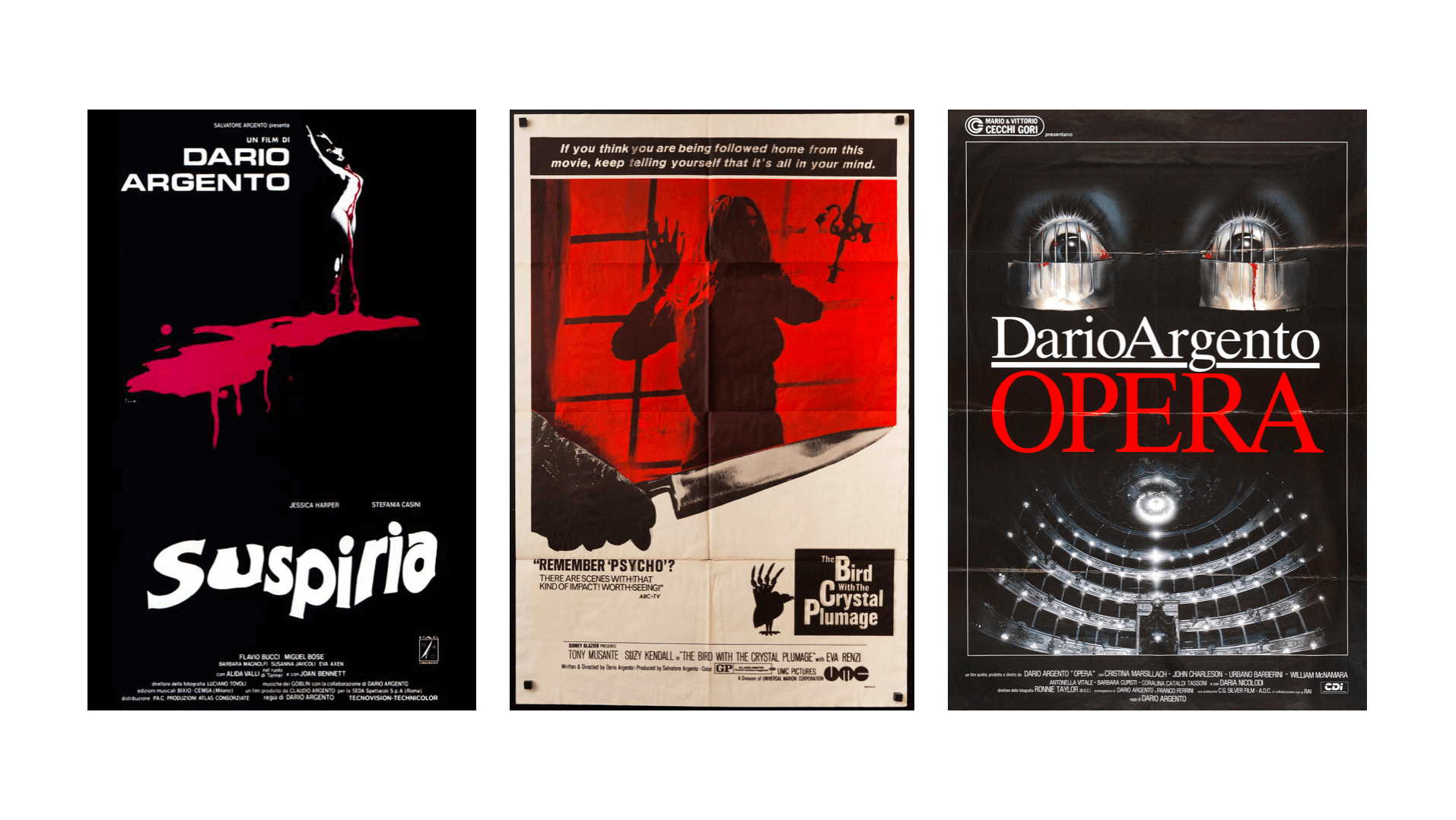

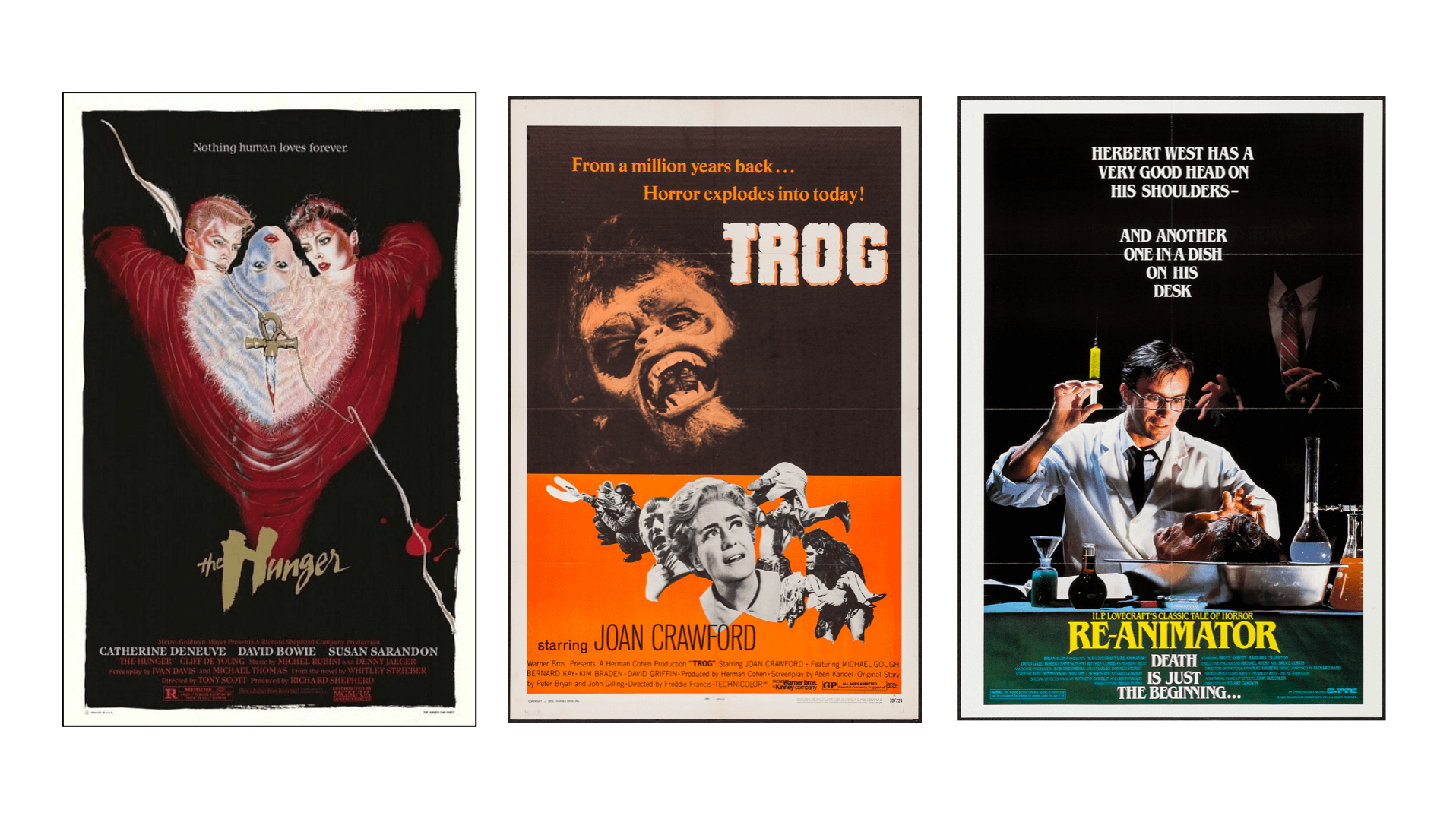

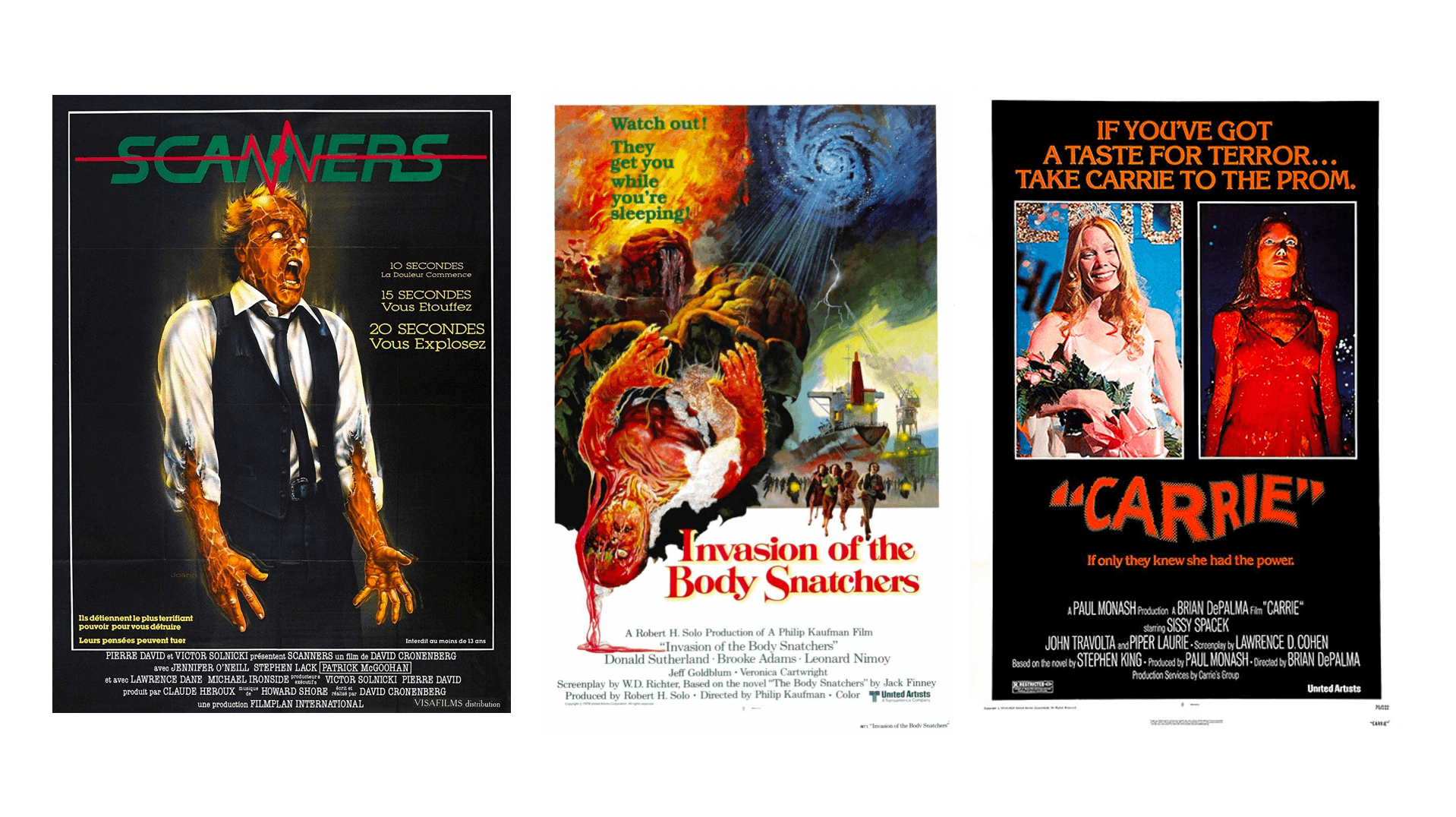

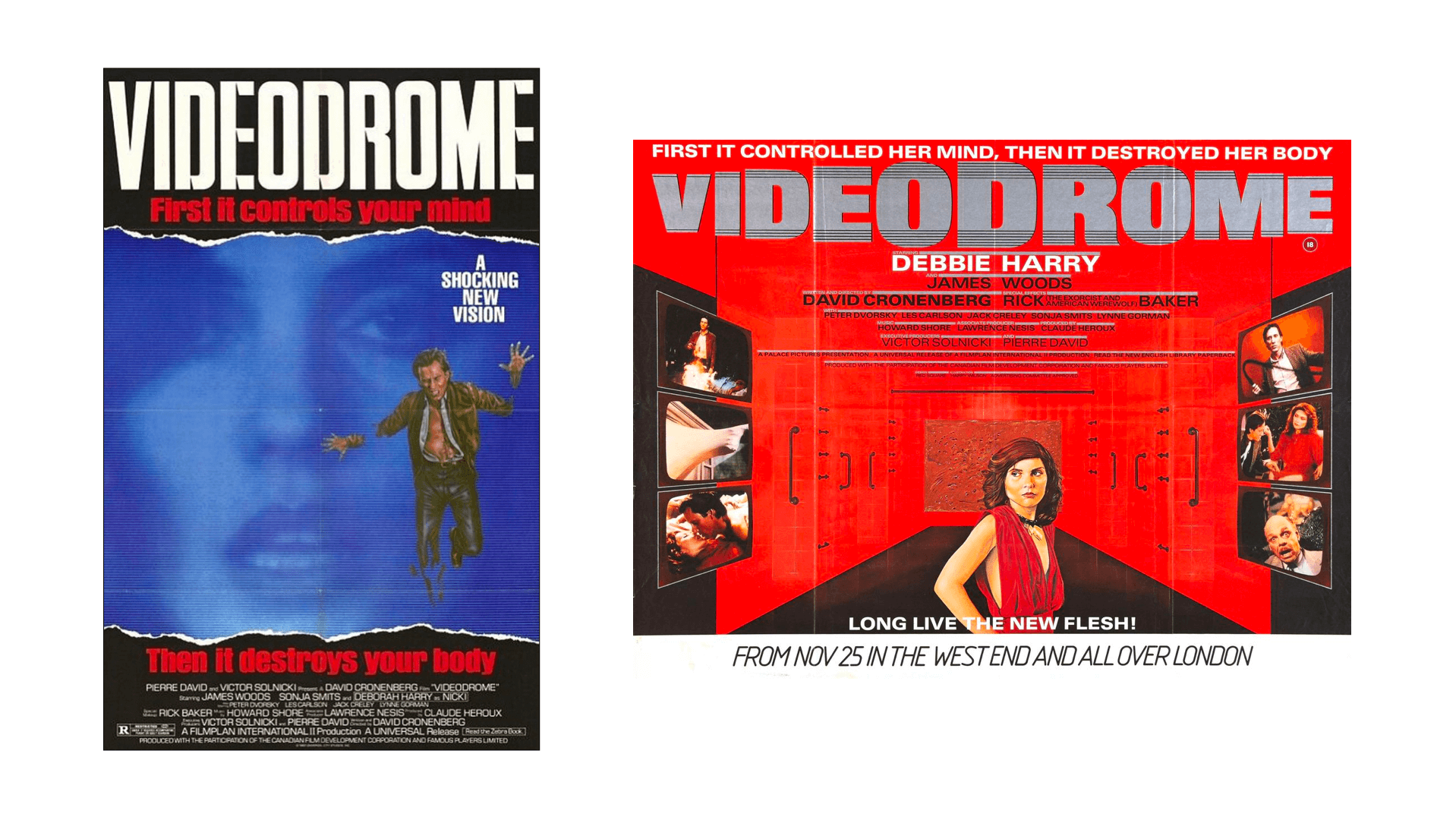

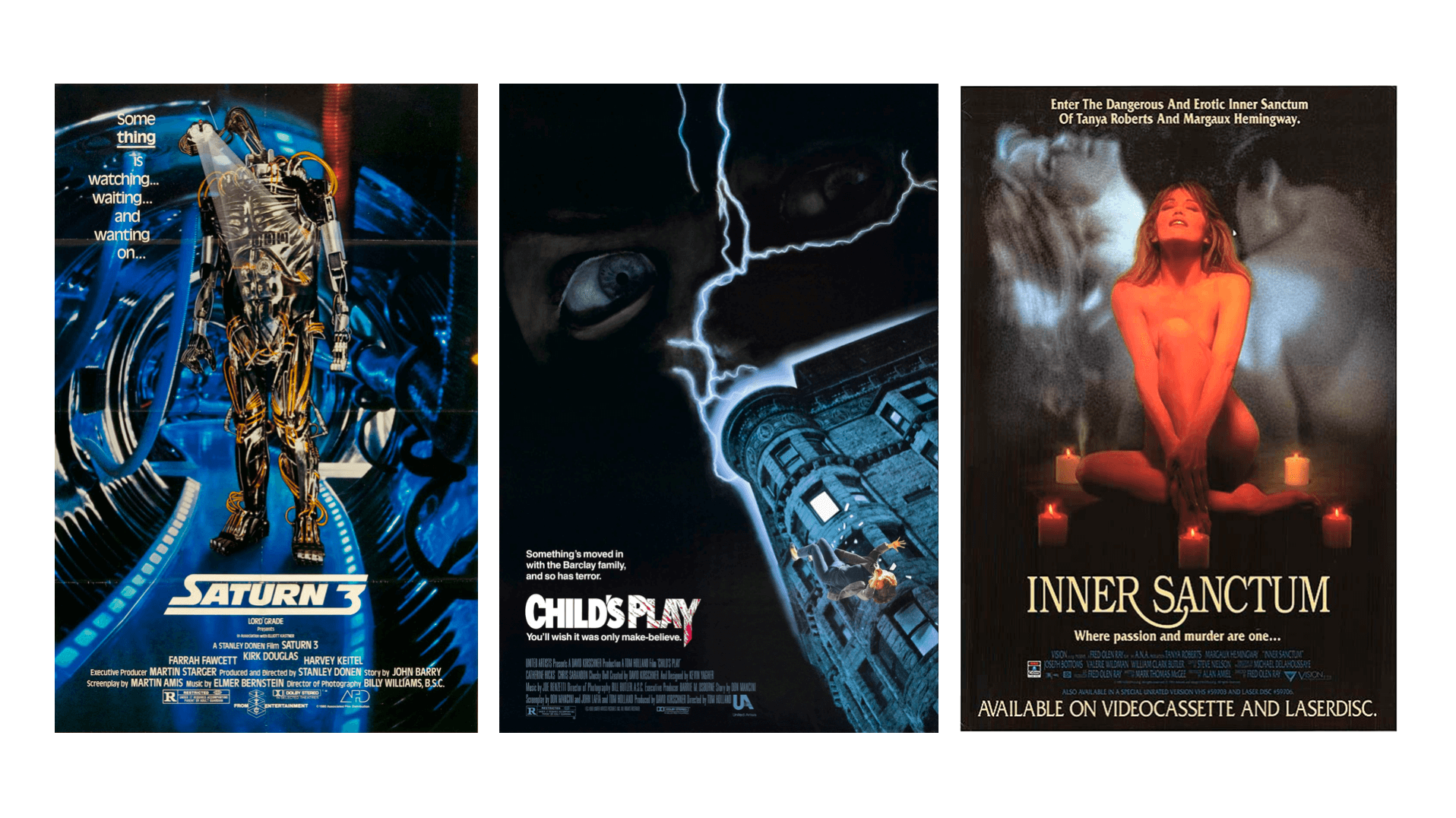

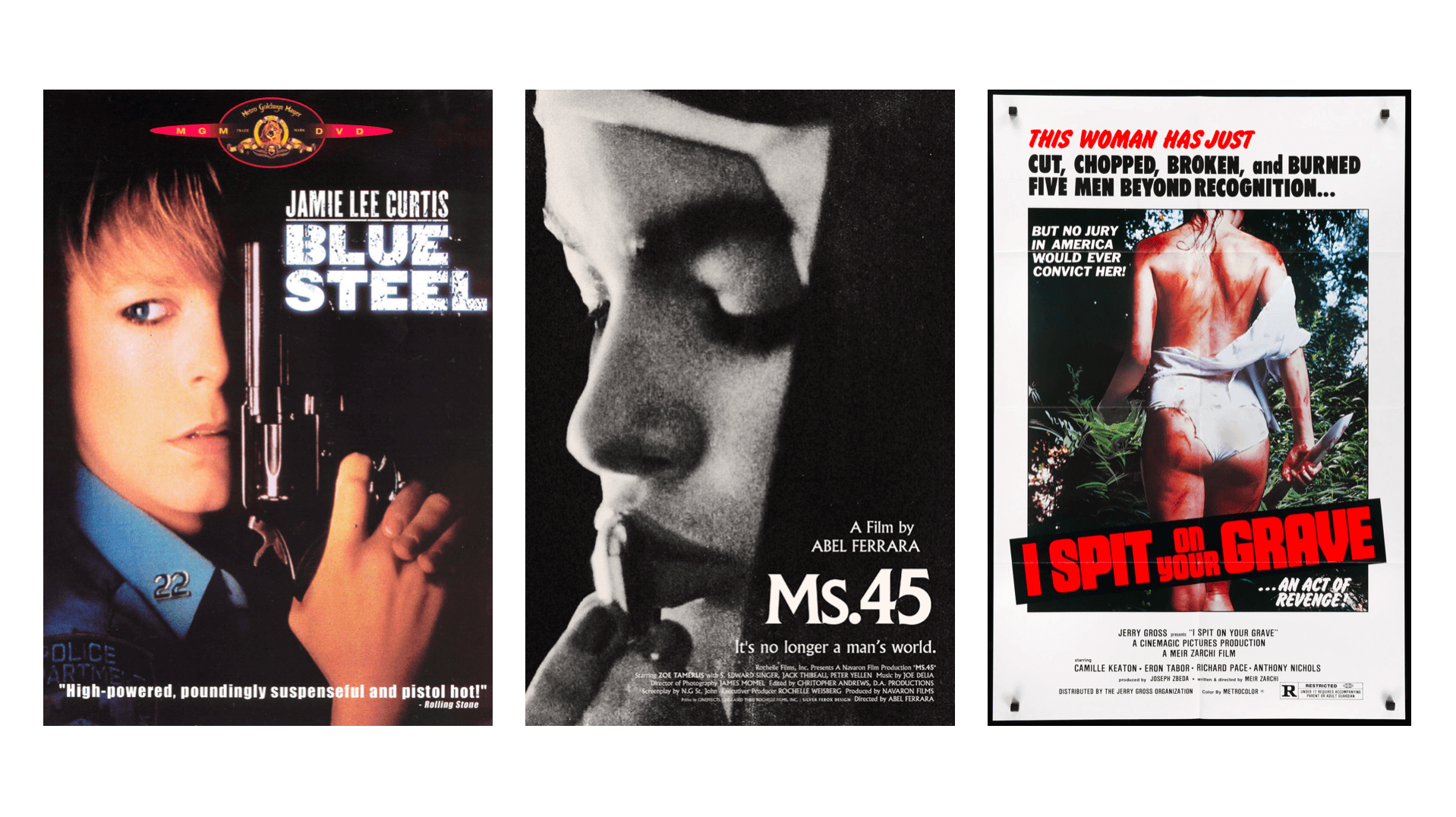

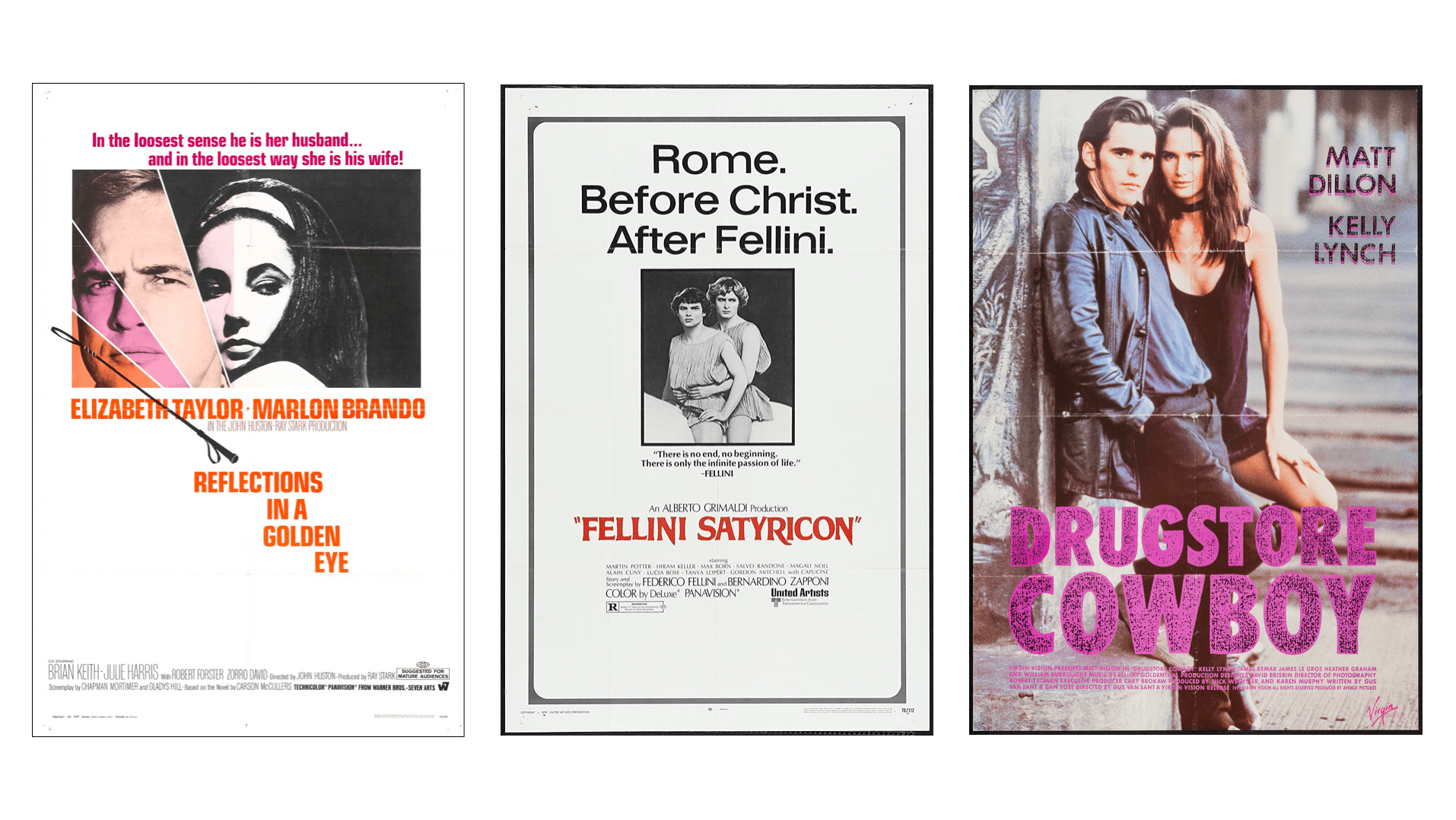

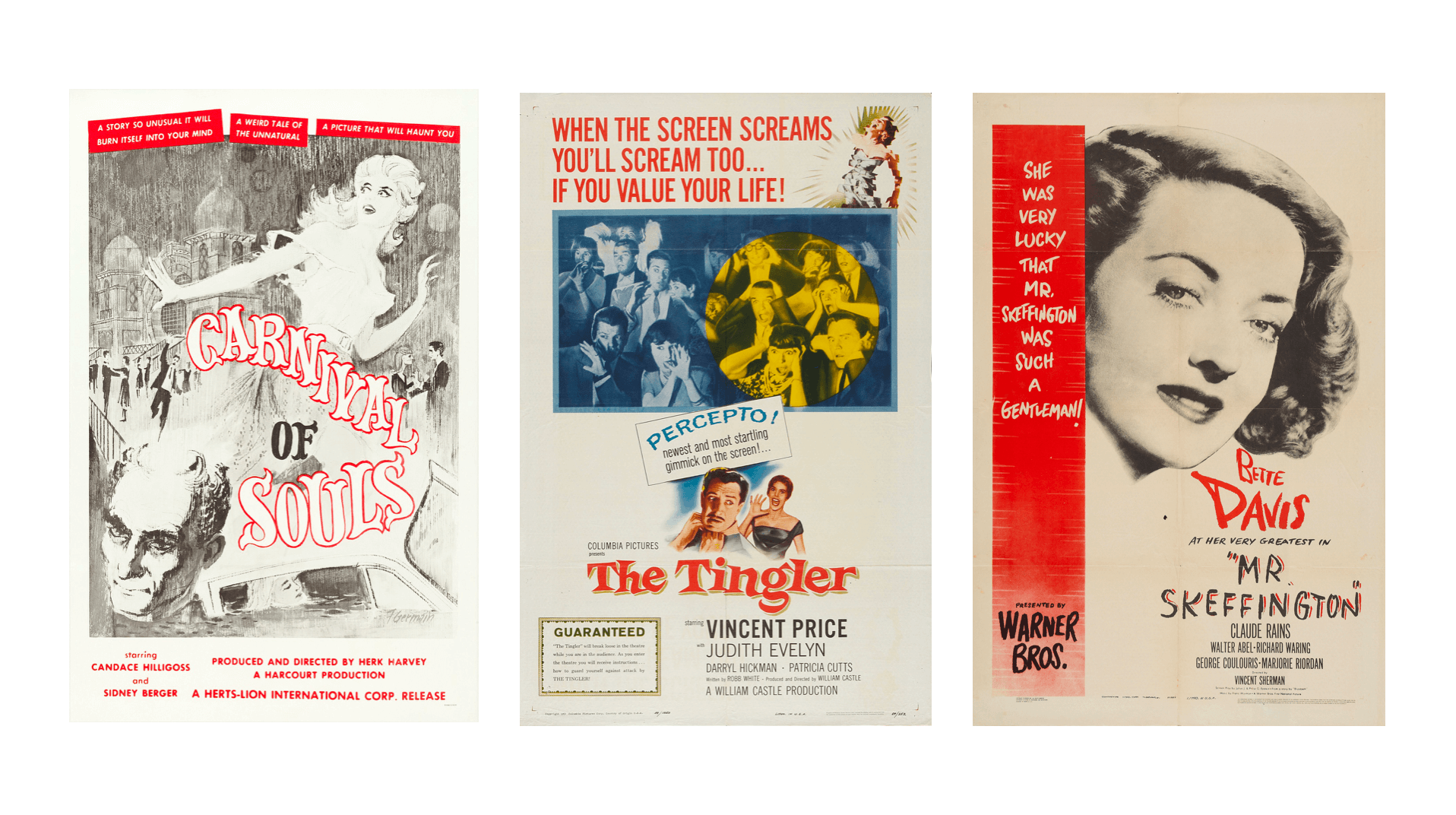

JT: These are some of the movies you write about in The Letters of Mina Harker:

Dodie Bellamy: Well clearly that book is a tribute to all sorts of trash cinema.

JT: These are some of the movies you write about in The Letters of Mina Harker:

The list goes on. But you start at The Roxie and I was wondering if this was an important place for you?

DB: Well I hardly ever go there now. I only go there if somebody I know has a movie, so you can imagine how marginal these movies are. But these types of theaters — The Roxie, The Castro, and there were some more punked out ones on Market Street that were really scary to go to when I first moved here — they were really important if you wanted to see anything informing some kind of vision outside the mainstream. There were a lot of them in San Francisco. The Roxie was a bit more avant-garde-ish than the others.

DB: Well I hardly ever go there now. I only go there if somebody I know has a movie, so you can imagine how marginal these movies are. But these types of theaters — The Roxie, The Castro, and there were some more punked out ones on Market Street that were really scary to go to when I first moved here — they were really important if you wanted to see anything informing some kind of vision outside the mainstream. There were a lot of them in San Francisco. The Roxie was a bit more avant-garde-ish than the others.

JT: There are so many scenes in The Letters of Mina Harker where you and KK (Kevin Killian) are watching movies, renting movies, taping movies on cable, such as erotic thrillers on Cinemax. The letters are all dated from the late-80s to the early-90s, a time when video stores were also social spaces.

DB: Especially if you went to a hip, cool one.

JT: Did you go to a cool one?

DB: No. But there are stories about how video stores have changed young boys' lives. Do you know Bradford Nordeen? He lives in LA. He wrote a piece recently about the video store he went to when he was growing up and how they had all these gay movies and experimental films and how the whole impact of the aesthetic of the store kind of formed him as a person.

JT: There aren’t that many video stores left in Los Angeles.

DB: People in LA seem to be picking up their lives a lot quicker than here. It feels like since COVID the physical world is becoming exoticized. Like it’s something you go into every once and a while, which is sick, right?

JT: Because we’ve quarantined for so long?

DB: Yeah and also just because our lives are so much online. I’m so glad they’re making us go back to classrooms next semester. Anything to have a human, material experience at this time is good.

JT: What are you teaching?

DB: I’m teaching a class on Sylvia Plath, and a class on Gender and Literature. I’m also teaching a grad fine arts seminar, which I really love, called Sex and Death. So who could complain about those classes, right?

JT: They sound great. So The Letters of Mina Harker is your debut novel, and on the first page, in the first letter, the first film you invoke is Nosferatu, which is also the first cinematic adaptation of Dracula. Nosferatu gives us the first Mina Harker in the history of movies, only here, for copyright reasons, her name has been switched to Ellen.

DB: Especially if you went to a hip, cool one.

JT: Did you go to a cool one?

DB: No. But there are stories about how video stores have changed young boys' lives. Do you know Bradford Nordeen? He lives in LA. He wrote a piece recently about the video store he went to when he was growing up and how they had all these gay movies and experimental films and how the whole impact of the aesthetic of the store kind of formed him as a person.

JT: There aren’t that many video stores left in Los Angeles.

DB: People in LA seem to be picking up their lives a lot quicker than here. It feels like since COVID the physical world is becoming exoticized. Like it’s something you go into every once and a while, which is sick, right?

JT: Because we’ve quarantined for so long?

DB: Yeah and also just because our lives are so much online. I’m so glad they’re making us go back to classrooms next semester. Anything to have a human, material experience at this time is good.

JT: What are you teaching?

DB: I’m teaching a class on Sylvia Plath, and a class on Gender and Literature. I’m also teaching a grad fine arts seminar, which I really love, called Sex and Death. So who could complain about those classes, right?

JT: They sound great. So The Letters of Mina Harker is your debut novel, and on the first page, in the first letter, the first film you invoke is Nosferatu, which is also the first cinematic adaptation of Dracula. Nosferatu gives us the first Mina Harker in the history of movies, only here, for copyright reasons, her name has been switched to Ellen.

DB: Why do you think that Dracula would have copyright issues?

JT: What happened with Nosferatu is that Murnau’s producers did not clear copyright permissions — they changed the names of the characters from Count Dracula to Count Orlok, from Mina to Ellen, and so on — but the widow of Bram Stoker sued for copyright infringement and the judge ruled in her favor, ordering that all prints of Murnau’s film be destroyed. So the film was nearly lost to history. It survived because some prints had already been sent abroad, from which copies were made. So it returns, and on the topic of returns, congratulations on the republication of your novel. It’s the book that keeps coming back.

JT: What happened with Nosferatu is that Murnau’s producers did not clear copyright permissions — they changed the names of the characters from Count Dracula to Count Orlok, from Mina to Ellen, and so on — but the widow of Bram Stoker sued for copyright infringement and the judge ruled in her favor, ordering that all prints of Murnau’s film be destroyed. So the film was nearly lost to history. It survived because some prints had already been sent abroad, from which copies were made. So it returns, and on the topic of returns, congratulations on the republication of your novel. It’s the book that keeps coming back.

DB: You know how Mina is in this liminal state between life and death? Well that’s where the fucking book has been. Do you want to hear the story about it?

JT: Definitely.

DB: Well originally Mina got rejected from a lot of places. It was surprisingly hard to publish. Hard Press was run by these really great poets, and I asked them, and sight unseen they said yes. The editor was Michael Gizzi, who was a poet and the brother of the poet Peter Gizzi. As many small presses do, Hard Press went under. Then Michael died x amount of years later. And then Eileen Myles said, “Why don’t you try to get the University of Wisconsin Press to reprint it?” Because Joan Larkin, who’s a poet, was editing a series for them. But they said no, they weren’t interested. So I wrote a letter and said, “Look, this book sells. Hard Press said this book sells, and it still has some life.” So they said “OK we’ll do it if we can have the galleys from Hard Press, so we don’t have to reset it.” So in 2014 the book was reprinted with all the typos, and I signed this agreement that gives me so little money it’s insane. Time passes and the book is just sitting there, it’s not getting any promotion, and they would not write me a check unless there were $100 in royalties. It was getting to the point that I would get a check every three years. That’s how this book was just rotting in obscurity. Finally I figure, it’s been 14 years. So I wrote and asked if I could have the rights back, and they said no. What they did, since it was a vague contract — and this is a problem for a lot of writers, not just me — is they decided to do it print-on-demand and they’re counting it as that book being in print. And they would not give me the rights back because they were making — this is how low the stakes are in this — they are making $300 a year on it themselves, so they thought it was a good investment. They’re holding my book hostage for this.

So finally Chris Kraus got this pro-bono attorney from a big law firm — on their website they brag about getting people out of Guantanamo, that’s what they brag about, so these are high-powered attorneys. They look at the contract and say, they have no right to this book. So they write the University of Wisconsin Press this letter, a very nice letter — and they weren’t scared one bit by this attorney. They just said no. We ended up having to pay them $1000, way more than I ever got for the book, to get the rights back. So for a time, Mina was half-dead — and now she really is coming back from the grave with this book.

JT: I like the new cover, with the painting by Laure Provoust. Was the first iteration of the project in the 1993 chapbook?

DB: Yeah, but some of it may have been in magazines before.

JT: I noticed in the new semiotext(e) edition there’s a catalogue that reads like a poem: 14 Hills, 6ix, ACTS, American Poetry Archive Newsletter, Athena Incognito, Barscheit, Big Allis, Bomb, Boo, Capilano Review, Farm, Gallery Works, Giantess: The Organ of the New Abjectionists, HOW(ever), Inciting Desire, Ink, Lingo, Lipstick Eleven, Mirago, Open 24 Hours, Ottotole, Poetics Journal, Red Wheelbarrow, River City, Russian River Writer’s Guild: Eight at Otis, Sodomite Invasion Review, Some Weird Sin, Talisman, Wray, and ZYZZYVA.

DB: Most of these are poetry magazines. It’s its own world, right? It has its own economy and its own hierarchies that exist outside of normal publishing. So I’m really coming out of a very different publishing world than most prose writers come out of. That was really great, and it also had its downsides, as anything does. I wanted to take this note on the publishing history out of the new edition of Mina, but Hedi, my editor, suggested I put it back in, so now you’re validating that that was a good decision.

JT: It’s like the provenance of an old painting, and some of the journal titles are great.

DB: Yeah I have all those magazines and I hope to place them in our archives [at Yale], so that they’re available, because you couldn’t find most of these.

JT: The Letters of Mina Harker somehow radiated across all these different places, which maybe connects with the spirit of multiplicity that’s in the writing itself?

DB: And if you looked at the magazines you would say, OK, Dodie was a big fish in a small pond, basically. It’s weird to have this really intense community that really takes itself seriously and pretty much has zero impact on the larger culture.

JT: In San Francisco?

DB: Not just San Francisco. Like the writers that Dennis Cooper brought together around Beyond Baroque, I was really involved with them. The poets in Vancouver around Kootenay Writing School. Poets in New York. Poets in Seattle. It was mostly West Coast and New York.

JT: And how would ideas flow between these different spaces?

DB: That’s what was interesting. It was all letter writing and traveling. I ran a reading series. I ended up being the Director of this literary nonprofit called Small Press Traffic, but before that I ran a reading series as a volunteer. So people would just come through town. We had no money. They would either get the door, or they get $35, and people would come from England to read — because that was where you read in San Francisco. So it was really beautiful in that way. You know we did that anthology, Kevin and I, Writers Who Love Too Much, about New Narrative, and the amount of connection that was going on before the internet is stunning. And not much of it was happening on the phone, because back then long-distance phone calls cost a lot of money. That’s why they have all these volumes of letters by writers, right? It’s one of the ways that people kept up.

JT: Do you enjoy reading letters? Epistolary exchanges?

DB: Not particularly. I know a lot of people who do. I studied so many things to write Mina — lots of theories of horror, horror movies, and then all sorts of other stuff. But I never really studied epistolary form. And then in the mid-90s I got this brief visiting professor job at Mills and I taught a class on epistolary fiction, or epistolary form maybe it was called. So then I did all this research on the history of it, but it was all after the fact.

JT: Definitely.

DB: Well originally Mina got rejected from a lot of places. It was surprisingly hard to publish. Hard Press was run by these really great poets, and I asked them, and sight unseen they said yes. The editor was Michael Gizzi, who was a poet and the brother of the poet Peter Gizzi. As many small presses do, Hard Press went under. Then Michael died x amount of years later. And then Eileen Myles said, “Why don’t you try to get the University of Wisconsin Press to reprint it?” Because Joan Larkin, who’s a poet, was editing a series for them. But they said no, they weren’t interested. So I wrote a letter and said, “Look, this book sells. Hard Press said this book sells, and it still has some life.” So they said “OK we’ll do it if we can have the galleys from Hard Press, so we don’t have to reset it.” So in 2014 the book was reprinted with all the typos, and I signed this agreement that gives me so little money it’s insane. Time passes and the book is just sitting there, it’s not getting any promotion, and they would not write me a check unless there were $100 in royalties. It was getting to the point that I would get a check every three years. That’s how this book was just rotting in obscurity. Finally I figure, it’s been 14 years. So I wrote and asked if I could have the rights back, and they said no. What they did, since it was a vague contract — and this is a problem for a lot of writers, not just me — is they decided to do it print-on-demand and they’re counting it as that book being in print. And they would not give me the rights back because they were making — this is how low the stakes are in this — they are making $300 a year on it themselves, so they thought it was a good investment. They’re holding my book hostage for this.

So finally Chris Kraus got this pro-bono attorney from a big law firm — on their website they brag about getting people out of Guantanamo, that’s what they brag about, so these are high-powered attorneys. They look at the contract and say, they have no right to this book. So they write the University of Wisconsin Press this letter, a very nice letter — and they weren’t scared one bit by this attorney. They just said no. We ended up having to pay them $1000, way more than I ever got for the book, to get the rights back. So for a time, Mina was half-dead — and now she really is coming back from the grave with this book.

JT: I like the new cover, with the painting by Laure Provoust. Was the first iteration of the project in the 1993 chapbook?

DB: Yeah, but some of it may have been in magazines before.

JT: I noticed in the new semiotext(e) edition there’s a catalogue that reads like a poem: 14 Hills, 6ix, ACTS, American Poetry Archive Newsletter, Athena Incognito, Barscheit, Big Allis, Bomb, Boo, Capilano Review, Farm, Gallery Works, Giantess: The Organ of the New Abjectionists, HOW(ever), Inciting Desire, Ink, Lingo, Lipstick Eleven, Mirago, Open 24 Hours, Ottotole, Poetics Journal, Red Wheelbarrow, River City, Russian River Writer’s Guild: Eight at Otis, Sodomite Invasion Review, Some Weird Sin, Talisman, Wray, and ZYZZYVA.

DB: Most of these are poetry magazines. It’s its own world, right? It has its own economy and its own hierarchies that exist outside of normal publishing. So I’m really coming out of a very different publishing world than most prose writers come out of. That was really great, and it also had its downsides, as anything does. I wanted to take this note on the publishing history out of the new edition of Mina, but Hedi, my editor, suggested I put it back in, so now you’re validating that that was a good decision.

JT: It’s like the provenance of an old painting, and some of the journal titles are great.

DB: Yeah I have all those magazines and I hope to place them in our archives [at Yale], so that they’re available, because you couldn’t find most of these.

JT: The Letters of Mina Harker somehow radiated across all these different places, which maybe connects with the spirit of multiplicity that’s in the writing itself?

DB: And if you looked at the magazines you would say, OK, Dodie was a big fish in a small pond, basically. It’s weird to have this really intense community that really takes itself seriously and pretty much has zero impact on the larger culture.

JT: In San Francisco?

DB: Not just San Francisco. Like the writers that Dennis Cooper brought together around Beyond Baroque, I was really involved with them. The poets in Vancouver around Kootenay Writing School. Poets in New York. Poets in Seattle. It was mostly West Coast and New York.

JT: And how would ideas flow between these different spaces?

DB: That’s what was interesting. It was all letter writing and traveling. I ran a reading series. I ended up being the Director of this literary nonprofit called Small Press Traffic, but before that I ran a reading series as a volunteer. So people would just come through town. We had no money. They would either get the door, or they get $35, and people would come from England to read — because that was where you read in San Francisco. So it was really beautiful in that way. You know we did that anthology, Kevin and I, Writers Who Love Too Much, about New Narrative, and the amount of connection that was going on before the internet is stunning. And not much of it was happening on the phone, because back then long-distance phone calls cost a lot of money. That’s why they have all these volumes of letters by writers, right? It’s one of the ways that people kept up.

JT: Do you enjoy reading letters? Epistolary exchanges?

DB: Not particularly. I know a lot of people who do. I studied so many things to write Mina — lots of theories of horror, horror movies, and then all sorts of other stuff. But I never really studied epistolary form. And then in the mid-90s I got this brief visiting professor job at Mills and I taught a class on epistolary fiction, or epistolary form maybe it was called. So then I did all this research on the history of it, but it was all after the fact.

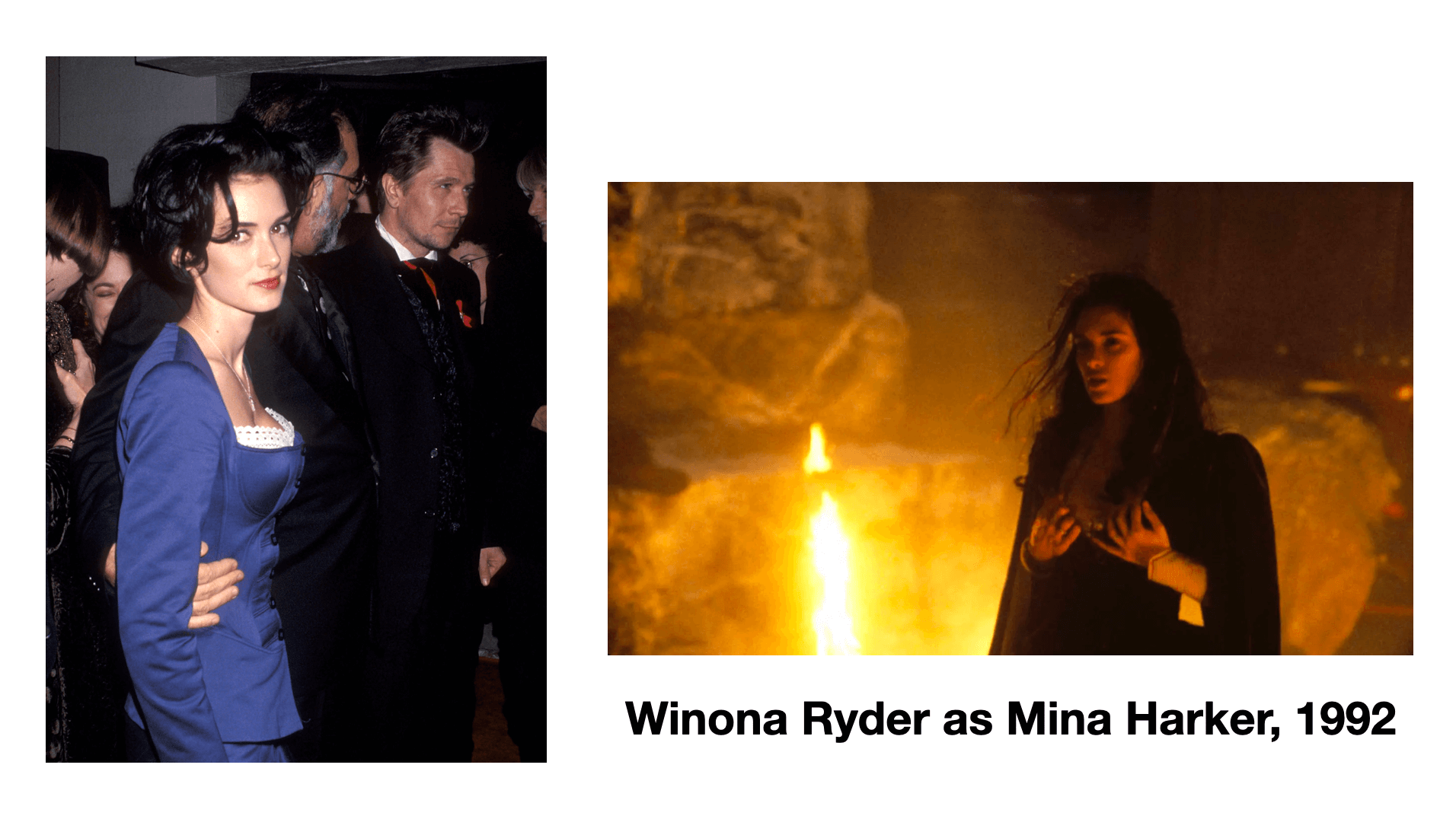

JT: In 1992 Winona Ryder played Mina Harker in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Here she is reading a letter:

DB: This is before movie vampires were teenagers.

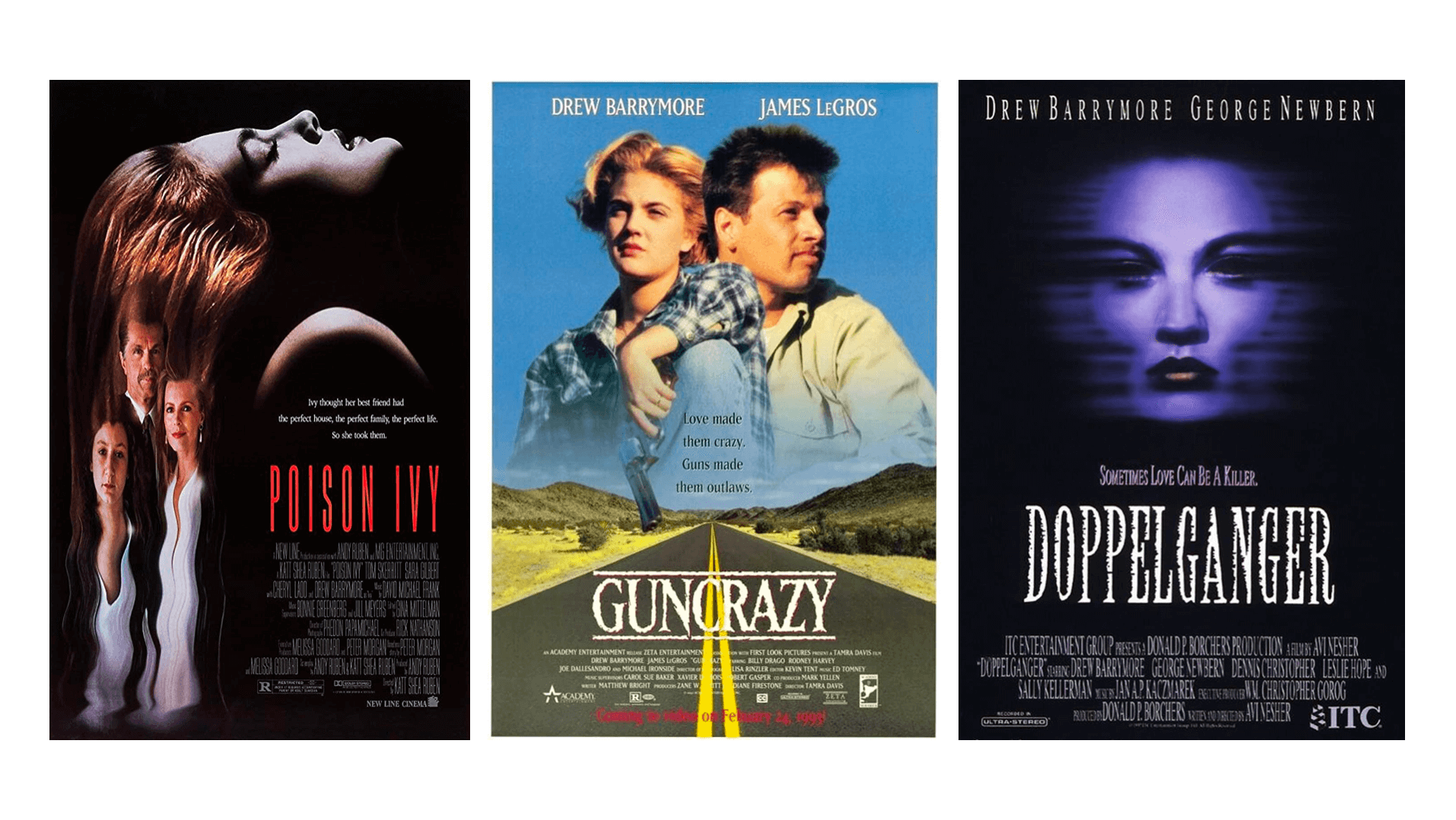

JT: Towards the end of The Letters of Mina Harker you write that you’ve become “a dedicated student of Drew Barrymore’s screen work,” so I thought you might like this next one, in which Drew Barrymore poses as — is it possible? — Mina Harker?

JT: Towards the end of The Letters of Mina Harker you write that you’ve become “a dedicated student of Drew Barrymore’s screen work,” so I thought you might like this next one, in which Drew Barrymore poses as — is it possible? — Mina Harker?

DB: Ooh, I don’t know if I saw that!

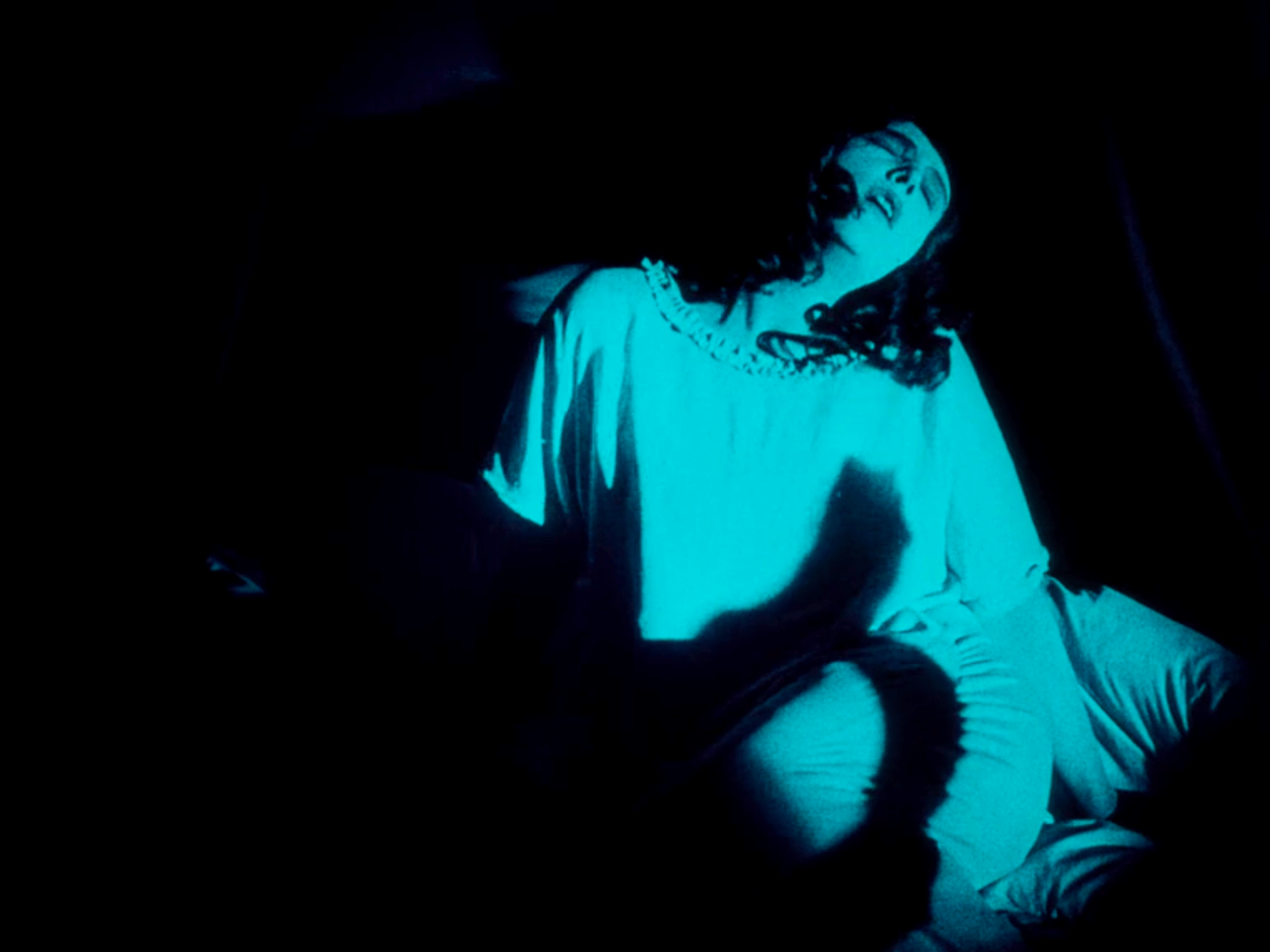

JT: It’s not in your book, and I haven’t seen it, but this shot is designed as a reenactment of that iconic bed scene from Nosferatu.

JT: It’s not in your book, and I haven’t seen it, but this shot is designed as a reenactment of that iconic bed scene from Nosferatu.

On the right is the first paperback edition of Dracula, published in 1947.

DB: I have that edition!

JT: You write about it in the novel. You write that KK gave you a copy. But to go back to 1992, there was something in the air. Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula is released, with Winona Ryder as Mina Harker. In 1992 Drew Barrymore also plays a role resembling Mina Harker in a scene that points to Nosferatu. And 1992 is the year of Tim Burton’s Batman Returns.

DB: I have that edition!

JT: You write about it in the novel. You write that KK gave you a copy. But to go back to 1992, there was something in the air. Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula is released, with Winona Ryder as Mina Harker. In 1992 Drew Barrymore also plays a role resembling Mina Harker in a scene that points to Nosferatu. And 1992 is the year of Tim Burton’s Batman Returns.

Tim Burton’s Batman came out in 1989 and made like $500 million, so Warner Brothers wanted him to make a sequel tout suite. But he went to 20th Century Fox instead, to make Edward Scissorhands. So Warner Brothers says to Burton, Look, make it your own thing, you can have final cut, and it can be a Tim Burton Batman! And it is. Burton added the character Max Shreck to the world of Batman Returns. Max Shreck is not from the Batman or DC universe. He’s named after the actor Max Schreck who played the vampire Count Orlok in Nosferatu. This is all happening in 1992, which I was curious about. Your novel The Letters of Mina Harker opens at The Roxy with a screening of Nosferatu, but you also mentioned a moment ago that your Mina Harker letters started before the 1993 chapbook. Do you remember what drew you to Dracula in the first place?

DB: I started the The Letters of Mina Harker before that, in the 80s, but honestly I don’t remember why I picked Dracula. I know I started doing it before I actually read the book. And then I read the book and I was so surprised because it’s all about letter writing, and journaling, and it was so perfect for what I was doing. So what started out as a coincidence made an impact as I moved forward. In the book I talk about Mina as a collector of data.

JT: So Mina Harker found you, or you found Mina Harker?

DB: Frankly, I was taught that Kathy Acker was, you know, the best writer that ever lived, so we were very much into appropriation in writing and writing through other things. That was what people were trying out, so I was looking for something to write through, but I couldn’t find anything that really worked for me, and then I just landed on Dracula, but mostly through movies. That’s where I started, with movies. I didn’t actually read that many horror novels in the process of writing this book. I read Stephen King’s theories on horror and things like that.

JT: Once you had the idea, what was the process like?

DB: Well these were written as letters, so whatever was happening in the letter was reflecting what was happening in my life. Nothing is made up. If you think that anything is made up in that book, nothing is made up! But I remember the way I would organize them as they got really complicated, because some of them are really complicated, right? What they would have is a higher thematic, like this one is about this topic, but I would never perhaps actively address the topic. I would have lists of quotes, and then I would do a lot of collaging. And then there would be narrative elements that keep being broken up by this woman going into this filmic reality which in today’s language would be like a state of trauma. The films are often traumatic, and they often represent some kind of intensity or sexual abandon that nerdy Dodie wasn’t capable of, but Mina totally could embody and absorb. It’s funny, I recently taught the “Introduction” to Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror. In reading it I recognized so many lines that have been collaged into The Letters of Mina Harker. Julia Kristeva was key for everyone that I hung out with. Her theory of abjection was really important. But the language is so off-putting that I would spoof it and really be moved by it at the same time.

JT: At one point in your novel Mina says “Call me Mia—Sigourney—Catherine Deneuve—Fay Wray—I am the heroine of every horror movie—fearlessly I turn in the direction of your words/telekinetic activities and demand: WHO ARE YOU AND WHAT DO YOU WANT FROM ME?” On the one hand it’s a novel about possession — Dodie possessed by Mina, Mina possessed at a moment, perhaps, by Mary Lou from Prom Night II — but I wonder what this passage, or this list of actors, calls to mind for you?

DB: It’s a collage, as I think we all are collages. But it’s about multiple personality narratives and possession narratives. Recently I was watching this Lynn Hershman movie, which has an interview with Karen Black in it, and I copied this quote from Karen Black because it seemed like a really good statement about writing, even though it isn’t about writing at all. “Acting is letting yourself be the effect of that which you created.” It’s kind of a boomerang thing, right? Like where is the creator and where is the person who’s being impacted by it? And they’re going back and forth. To me that seemed an interesting way of looking at one of my goals in writing, and that again would go back to acting.

JT: The book is called The Letters of Mina Harker, so it’s organized as a series of letters. The first is from July 3, 1986 and the last is October 17, 1994.

DB: That’s a lie. The letters were written long before 1986, but they needed a place to start.

JT: Why 1986?

DB: It starts at the wedding night of KK and Dodie. The traditional female novel ends with the wedding, so that's where I where I began.

JT: The first letter begins “Dear Reader,” which calls to mind that 19th century tradition.

DB: One of the Brontës did that. “Dear Reader, I married him” is a line from Jane Eyre.

JT: The first sentence of the first letter is not unusual. But the second sentence takes off like a magic carpet. Suddenly we’re in a mode of writing that pushes against syntactical norms as punctuation becomes irregular, narrative voice multiplies, italicizations intrude, and the pages begin to palpitate with poetic energy. Can you read me the second paragraph? It’s just a single, standalone sentence.

DB: “The monstrous and the formless have as much right as anybody else.”

JT: This seems like an important line?

DB: The monstrous and the formless would be the form of the novel, too, right?

JT: Do you have a working definition of the monster or the monstrous?

DB: Well let’s see. I spent sooo much time thinking and writing about this, but now it’s kind of ancient. One of the ways I thought about the monster, going back to the theory — who wrote Purity and Danger?

JT: Mary Douglas.

DB: Yeah Mary Douglas. Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror was basically Purity and Danger written with a psychological spin. Mary Douglas talks about cultural categories, like we all live in these specific cultural categories — living versus dead, one verses many — and horror and comedy both really play upon them. Male versus female is a cultural category that’s currently being torn apart, and that’s really destabilizing for a lot of people, because a core way they define the world is being readjusted.

The monster according to Mary Douglas — say a baby is born and they do not fit the norm of what a society calls a baby, what do they do with it? The monster is often something that is between cultural categories and doesn’t quite fit. So I would say the monster, for me, becomes something that is in between, or just outside the norm in a very broad sense. For a while I had a long-term temp job, which I mined in The Letters of Mina Harker, where I was working in the Radiology Department of UCSF, and for a while I worked for this doctor, and she would have me do research for her articles — even though I was just this fucking temp, with no training in medicine or anatomy.

JT: The doctor as vampire.

DB: Yeah. One of the journals was called the Journal of Teratology, for babies that had birth defects. They called it that. Teratology means the study of monsters.They were still using these terms in the early-90s.

JT: So you were thinking about the monster as something that challenges categorical boundaries. In your research were there any movie monsters you thought were particularly interesting?

DB: I started the The Letters of Mina Harker before that, in the 80s, but honestly I don’t remember why I picked Dracula. I know I started doing it before I actually read the book. And then I read the book and I was so surprised because it’s all about letter writing, and journaling, and it was so perfect for what I was doing. So what started out as a coincidence made an impact as I moved forward. In the book I talk about Mina as a collector of data.

JT: So Mina Harker found you, or you found Mina Harker?

DB: Frankly, I was taught that Kathy Acker was, you know, the best writer that ever lived, so we were very much into appropriation in writing and writing through other things. That was what people were trying out, so I was looking for something to write through, but I couldn’t find anything that really worked for me, and then I just landed on Dracula, but mostly through movies. That’s where I started, with movies. I didn’t actually read that many horror novels in the process of writing this book. I read Stephen King’s theories on horror and things like that.

JT: Once you had the idea, what was the process like?

DB: Well these were written as letters, so whatever was happening in the letter was reflecting what was happening in my life. Nothing is made up. If you think that anything is made up in that book, nothing is made up! But I remember the way I would organize them as they got really complicated, because some of them are really complicated, right? What they would have is a higher thematic, like this one is about this topic, but I would never perhaps actively address the topic. I would have lists of quotes, and then I would do a lot of collaging. And then there would be narrative elements that keep being broken up by this woman going into this filmic reality which in today’s language would be like a state of trauma. The films are often traumatic, and they often represent some kind of intensity or sexual abandon that nerdy Dodie wasn’t capable of, but Mina totally could embody and absorb. It’s funny, I recently taught the “Introduction” to Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror. In reading it I recognized so many lines that have been collaged into The Letters of Mina Harker. Julia Kristeva was key for everyone that I hung out with. Her theory of abjection was really important. But the language is so off-putting that I would spoof it and really be moved by it at the same time.

JT: At one point in your novel Mina says “Call me Mia—Sigourney—Catherine Deneuve—Fay Wray—I am the heroine of every horror movie—fearlessly I turn in the direction of your words/telekinetic activities and demand: WHO ARE YOU AND WHAT DO YOU WANT FROM ME?” On the one hand it’s a novel about possession — Dodie possessed by Mina, Mina possessed at a moment, perhaps, by Mary Lou from Prom Night II — but I wonder what this passage, or this list of actors, calls to mind for you?

DB: It’s a collage, as I think we all are collages. But it’s about multiple personality narratives and possession narratives. Recently I was watching this Lynn Hershman movie, which has an interview with Karen Black in it, and I copied this quote from Karen Black because it seemed like a really good statement about writing, even though it isn’t about writing at all. “Acting is letting yourself be the effect of that which you created.” It’s kind of a boomerang thing, right? Like where is the creator and where is the person who’s being impacted by it? And they’re going back and forth. To me that seemed an interesting way of looking at one of my goals in writing, and that again would go back to acting.

JT: The book is called The Letters of Mina Harker, so it’s organized as a series of letters. The first is from July 3, 1986 and the last is October 17, 1994.

DB: That’s a lie. The letters were written long before 1986, but they needed a place to start.

JT: Why 1986?

DB: It starts at the wedding night of KK and Dodie. The traditional female novel ends with the wedding, so that's where I where I began.

JT: The first letter begins “Dear Reader,” which calls to mind that 19th century tradition.

DB: One of the Brontës did that. “Dear Reader, I married him” is a line from Jane Eyre.

JT: The first sentence of the first letter is not unusual. But the second sentence takes off like a magic carpet. Suddenly we’re in a mode of writing that pushes against syntactical norms as punctuation becomes irregular, narrative voice multiplies, italicizations intrude, and the pages begin to palpitate with poetic energy. Can you read me the second paragraph? It’s just a single, standalone sentence.

DB: “The monstrous and the formless have as much right as anybody else.”

JT: This seems like an important line?

DB: The monstrous and the formless would be the form of the novel, too, right?

JT: Do you have a working definition of the monster or the monstrous?

DB: Well let’s see. I spent sooo much time thinking and writing about this, but now it’s kind of ancient. One of the ways I thought about the monster, going back to the theory — who wrote Purity and Danger?

JT: Mary Douglas.

DB: Yeah Mary Douglas. Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror was basically Purity and Danger written with a psychological spin. Mary Douglas talks about cultural categories, like we all live in these specific cultural categories — living versus dead, one verses many — and horror and comedy both really play upon them. Male versus female is a cultural category that’s currently being torn apart, and that’s really destabilizing for a lot of people, because a core way they define the world is being readjusted.

The monster according to Mary Douglas — say a baby is born and they do not fit the norm of what a society calls a baby, what do they do with it? The monster is often something that is between cultural categories and doesn’t quite fit. So I would say the monster, for me, becomes something that is in between, or just outside the norm in a very broad sense. For a while I had a long-term temp job, which I mined in The Letters of Mina Harker, where I was working in the Radiology Department of UCSF, and for a while I worked for this doctor, and she would have me do research for her articles — even though I was just this fucking temp, with no training in medicine or anatomy.

JT: The doctor as vampire.

DB: Yeah. One of the journals was called the Journal of Teratology, for babies that had birth defects. They called it that. Teratology means the study of monsters.They were still using these terms in the early-90s.

JT: So you were thinking about the monster as something that challenges categorical boundaries. In your research were there any movie monsters you thought were particularly interesting?

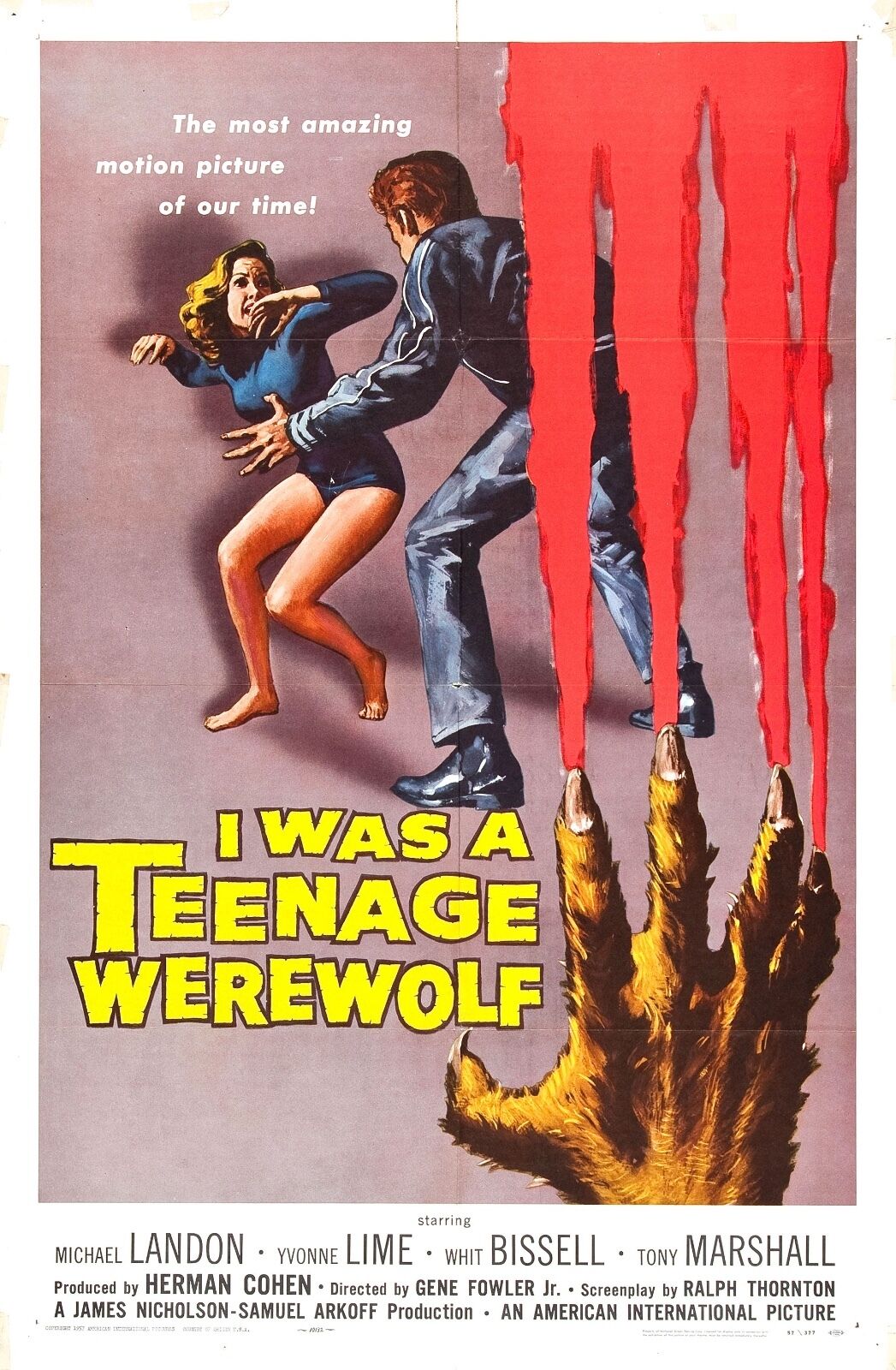

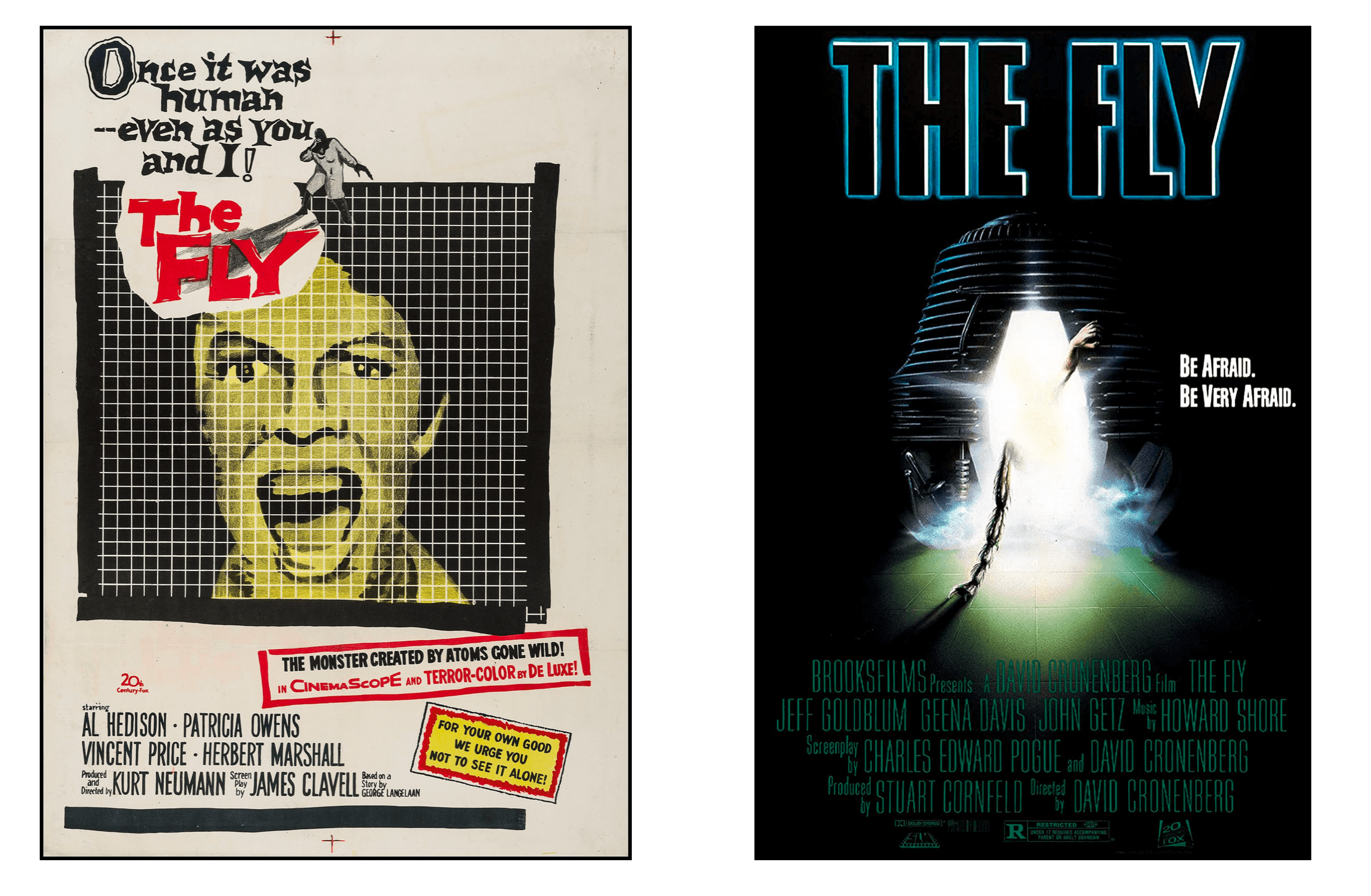

DB: The Creature from the Black Lagoon. I don’t know if the creature is in Mina but I wrote a prose poem about The Creature from the Black Lagoon. It’s interesting, when I was in Junior High, just a nerdy girl trying to survive, I was totally into monsters and I bought monster movie magazines. What’s funny is that they terrified me so much. Like that movie The Fly. I can’t remember if I wrote about it in Mina but even the poster of I Was a Teenage Werewolf scared me.

But I was really drawn to these movies. I guess getting involved with Kevin and the New Narrative people was permission to get rid of the hoity-toity you’re too good for this stuff and go back to what I was interested in as a child.

JT: What do you mean about New Narrative in this context?

DB: The interest in pop culture and how culture creates personality, and that blurring of the cultural self and the individual self and this expanded notion of what an individual self was. A lot of women, like Bhanu Kapil, the poet, are really interested in the monster because it becomes a symbol of the female experience of alienation. So many women have body dysmorphia and feel a sense of otherness, so the monster becomes a projection of themselves. Carol Clover wrote that book on the final girl and how slasher movies were really about men projecting their vulnerabilities. Her view was that men in the audience would identify with the female victims on screen, which I thought was an interesting idea.

So when I would watch horror films I really really would try to get rid of the censor, no matter how cheesy it was, to be the ideal audience that the director was intending it for, and just take it in and respond to it on an emotional and psychological level. I really do believe that things do not enter the culture from some high theory and then trickle down. Things start in some shitty horror film. That’s where you see what’s happening in the culture, and then it moves its way up.

JT: Dario Argento comes up numerous times, and you also metion having an Argento poster on the wall of your apartment.

DB: Yeah, but again that was through Kathy Acker’s influence. She’s the one who told us about Argento, and we just went crazy with it. And then Kevin wrote a whole book of poems called Argento Series. He talks about the AIDS epidemic through Argento’s movies.

JT: What do you mean about New Narrative in this context?

DB: The interest in pop culture and how culture creates personality, and that blurring of the cultural self and the individual self and this expanded notion of what an individual self was. A lot of women, like Bhanu Kapil, the poet, are really interested in the monster because it becomes a symbol of the female experience of alienation. So many women have body dysmorphia and feel a sense of otherness, so the monster becomes a projection of themselves. Carol Clover wrote that book on the final girl and how slasher movies were really about men projecting their vulnerabilities. Her view was that men in the audience would identify with the female victims on screen, which I thought was an interesting idea.

So when I would watch horror films I really really would try to get rid of the censor, no matter how cheesy it was, to be the ideal audience that the director was intending it for, and just take it in and respond to it on an emotional and psychological level. I really do believe that things do not enter the culture from some high theory and then trickle down. Things start in some shitty horror film. That’s where you see what’s happening in the culture, and then it moves its way up.

JT: Dario Argento comes up numerous times, and you also metion having an Argento poster on the wall of your apartment.

DB: Yeah, but again that was through Kathy Acker’s influence. She’s the one who told us about Argento, and we just went crazy with it. And then Kevin wrote a whole book of poems called Argento Series. He talks about the AIDS epidemic through Argento’s movies.

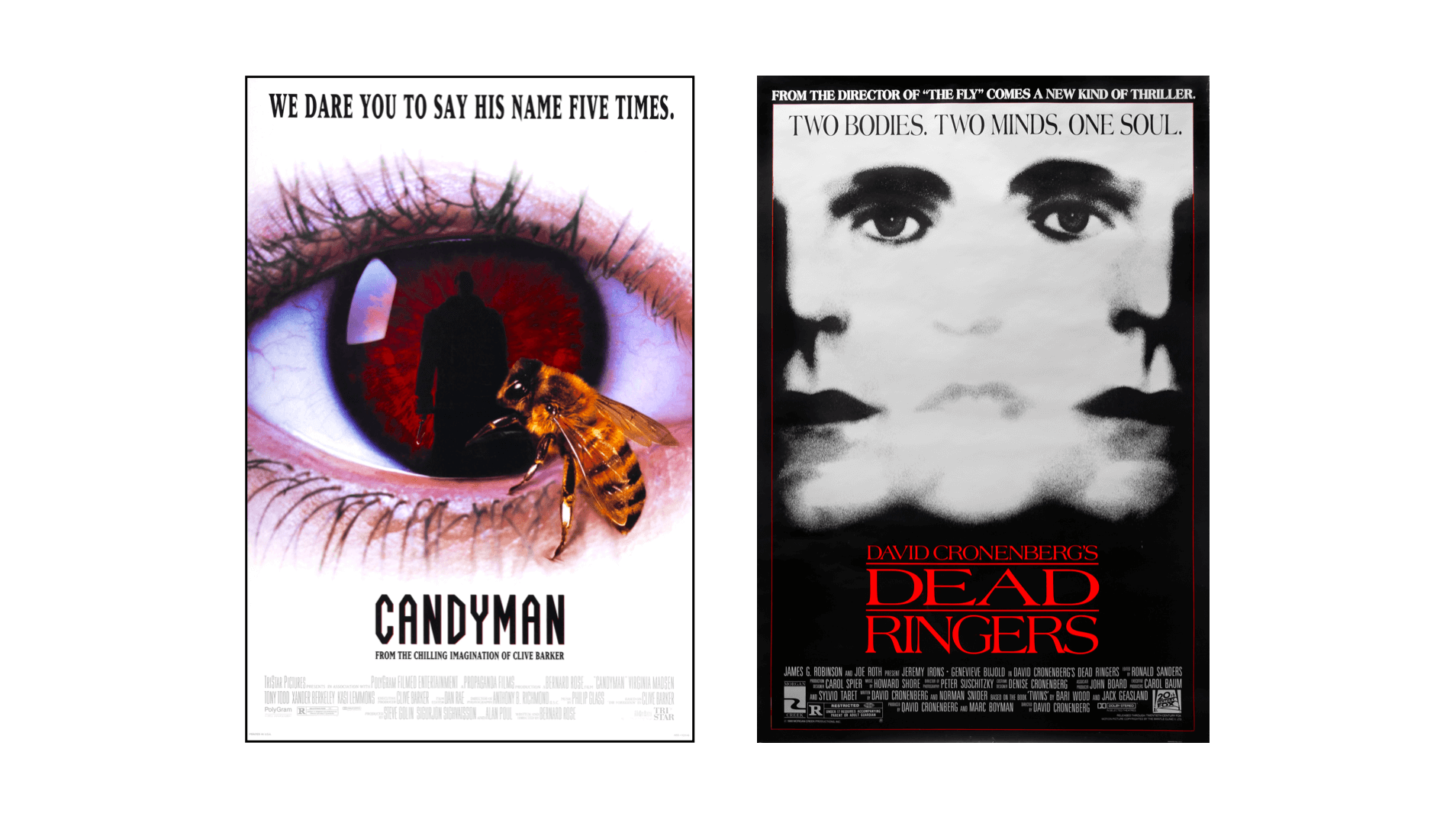

JT: Was Cronenberg somebody you were particularly interested in?

DB: Yeah, well his movies were pretty experimental. But the early ones, yeah. They were so frenzied. They’re very much body horror, right?

JT: Definitely. Doesn’t Cronenberg have a literary background?

DB: I think so. I had dinner with him one time, because he went to college with this friend of mine. They called him David but I didn’t know until afterwards that I had had dinner with David Cronenberg! Can you imagine? It sounds like I made it up.

JT: I can sense an affinity. Your writing here is very visceral, and immersive. Was body horror a sub-genre of interest?

DB: Yeah, especially transformation scenes. I just love them, when suddenly a person’s eyes are bulging and different things are happening to their body and it’s out of control. It’s such an important trope in horror movies. Part of this resonates on a personal level, since I had anxiety attacks and drug flashbacks and when I would have a drug flashback it felt like those horror movies. It’s one of the most horrible things to have your body just go haywire. I think some of that is written into the book.

JT: I wonder if there’s something distinctly pre-internet about the physical qualities of the writing? As in life before smartphones...

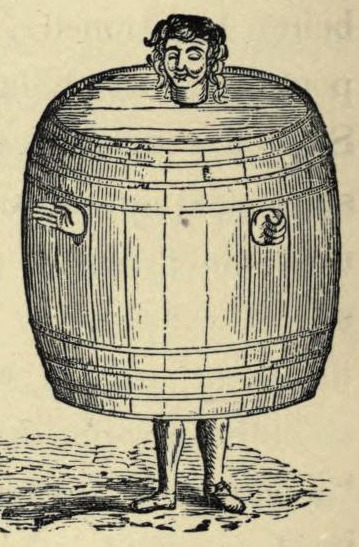

DB: All the quotes are from books, which were written on in the margins. I’m currently going back to this novel that I abandoned in the late-90s. I took ten random pages — it’s very disjunct, this one part — and worked them up. And it was so interesting to notice the difference between writing styles, between the 90s and now. So anyway I’m writing about barrel pilories.

JT: What’s that?

DB: Well that’s the way they would humiliate people. They would put a barrel over their head and then make them walk around. Sometimes they would cut holes for their hands to go through.

DB: Yeah, well his movies were pretty experimental. But the early ones, yeah. They were so frenzied. They’re very much body horror, right?

JT: Definitely. Doesn’t Cronenberg have a literary background?

DB: I think so. I had dinner with him one time, because he went to college with this friend of mine. They called him David but I didn’t know until afterwards that I had had dinner with David Cronenberg! Can you imagine? It sounds like I made it up.

JT: I can sense an affinity. Your writing here is very visceral, and immersive. Was body horror a sub-genre of interest?

DB: Yeah, especially transformation scenes. I just love them, when suddenly a person’s eyes are bulging and different things are happening to their body and it’s out of control. It’s such an important trope in horror movies. Part of this resonates on a personal level, since I had anxiety attacks and drug flashbacks and when I would have a drug flashback it felt like those horror movies. It’s one of the most horrible things to have your body just go haywire. I think some of that is written into the book.

JT: I wonder if there’s something distinctly pre-internet about the physical qualities of the writing? As in life before smartphones...

DB: All the quotes are from books, which were written on in the margins. I’m currently going back to this novel that I abandoned in the late-90s. I took ten random pages — it’s very disjunct, this one part — and worked them up. And it was so interesting to notice the difference between writing styles, between the 90s and now. So anyway I’m writing about barrel pilories.

JT: What’s that?

DB: Well that’s the way they would humiliate people. They would put a barrel over their head and then make them walk around. Sometimes they would cut holes for their hands to go through.

JT: Wait who did this?

DB: This is like an old-fashioned punishment, like around the time they burned witches. That type of thing. What I was editing was bits from my journal, and in your journal you’re talking to yourself. At the time I didn’t talk much about the barrel pillories, but it sounded interesting where I was taking it. Now with the internet it took like two minutes to have the whole history of barrel pillories, the various different types of them — you know what I mean? It felt almost an invasion of this writing from the 90s, to suddenly add all this information I got online. But it made it a better paragraph. It’s a really different process. I spend so much time researching.

JT: You said it made it a better paragraph and you called the writing disjunct. Do you mean you have some words on the page and as you’re composing them in a sequence there’s a disjunctive intrusion of information from an outside source?

DB: Well it just shows how false writing is. This is meant to read as a journal entry, but, how do I say it? It wants to have a surface that is a little rough and is moving from topic to topic.

JT: When you say surface, you mean surface as opposed to what?

DB: I mean when you look at it, does it look like a cohesive narrative? No. Does it look all smooth and worked out and perfected? No.

But it is. I had the ten pages. I cut it down to 4 to 5 pages. And then wrote it out to 6 pages. But I stayed up all night. I mean we’re talking to 5 in the morning, editing these ten pages.

JT: So is this a new way of composing, or is this is something that has been part of the practice for some time?

DB: You mean using the internet?

JT: I guess it sounds silly if I phrase it that way.

DB: The writing now is much more normal on its surface than Mina. Some people love Mina, and other people don’t have the patience for it, especially now. But it’s a book that’s supposed to be about cultural overwhelm. She’s overwhelmed. She’s overwhelmed by sex, she’s overwhelmed by all these images, she’s overwhelmed by how you had to read literary theory in order to survive in the culture of 80s and 90s San Francisco, and probably in Los Angles, too. In some ways there's a violence of having to read that stuff. So I would often take paragraphs straight out of some theory book and then change words to sexualize it and undercut it. So a lot of the lines where it sounds like it’s this intense intimacy it’s just some line taken out of a theory book. I always wanted the theory to feel an intrusion, or denatured. Something that’s like an assault.

JT: On the topic of theory there was one thing I was sorta curious about and that was the translation of Georges Bataille’s Erotism, published by City Lights there in San Francisco in the mid-80s.

DB: Who translated it?

JT: Mary Dalwood. It came out in 1986.

DB: The person who plays Van Helsing, or not “plays Van Helsing” but the person Van Helsing in my book is based on is a translator of Bataille.

JT: I’m not sure I’d call it a slip to say that somebody “plays Van Helsing,” because The Letters of Mina Harker is steeped in a filmic sensibility. Of course it’s about many other things too, like sex and death and the erotics of writing, but “Rapid cut from Reagan’s toothy popcorn smile to the towel draped over the busboy’s pumped-up forearm to a medium shot of exicted Secret Service men to a close-up of a finger cramped on a trigger.” Or “imagine an Eisenstein montage of calendar pages flying through the air like angry birds, my face intercut with a baby carriage rocking down a staircase.”

DB: Well it very much is a tribute to cinema and it’s also exploring the question of where does the self exist with all this input, right?

DB: This is like an old-fashioned punishment, like around the time they burned witches. That type of thing. What I was editing was bits from my journal, and in your journal you’re talking to yourself. At the time I didn’t talk much about the barrel pillories, but it sounded interesting where I was taking it. Now with the internet it took like two minutes to have the whole history of barrel pillories, the various different types of them — you know what I mean? It felt almost an invasion of this writing from the 90s, to suddenly add all this information I got online. But it made it a better paragraph. It’s a really different process. I spend so much time researching.

JT: You said it made it a better paragraph and you called the writing disjunct. Do you mean you have some words on the page and as you’re composing them in a sequence there’s a disjunctive intrusion of information from an outside source?

DB: Well it just shows how false writing is. This is meant to read as a journal entry, but, how do I say it? It wants to have a surface that is a little rough and is moving from topic to topic.

JT: When you say surface, you mean surface as opposed to what?

DB: I mean when you look at it, does it look like a cohesive narrative? No. Does it look all smooth and worked out and perfected? No.

But it is. I had the ten pages. I cut it down to 4 to 5 pages. And then wrote it out to 6 pages. But I stayed up all night. I mean we’re talking to 5 in the morning, editing these ten pages.

JT: So is this a new way of composing, or is this is something that has been part of the practice for some time?

DB: You mean using the internet?

JT: I guess it sounds silly if I phrase it that way.

DB: The writing now is much more normal on its surface than Mina. Some people love Mina, and other people don’t have the patience for it, especially now. But it’s a book that’s supposed to be about cultural overwhelm. She’s overwhelmed. She’s overwhelmed by sex, she’s overwhelmed by all these images, she’s overwhelmed by how you had to read literary theory in order to survive in the culture of 80s and 90s San Francisco, and probably in Los Angles, too. In some ways there's a violence of having to read that stuff. So I would often take paragraphs straight out of some theory book and then change words to sexualize it and undercut it. So a lot of the lines where it sounds like it’s this intense intimacy it’s just some line taken out of a theory book. I always wanted the theory to feel an intrusion, or denatured. Something that’s like an assault.

JT: On the topic of theory there was one thing I was sorta curious about and that was the translation of Georges Bataille’s Erotism, published by City Lights there in San Francisco in the mid-80s.

DB: Who translated it?

JT: Mary Dalwood. It came out in 1986.

DB: The person who plays Van Helsing, or not “plays Van Helsing” but the person Van Helsing in my book is based on is a translator of Bataille.

JT: I’m not sure I’d call it a slip to say that somebody “plays Van Helsing,” because The Letters of Mina Harker is steeped in a filmic sensibility. Of course it’s about many other things too, like sex and death and the erotics of writing, but “Rapid cut from Reagan’s toothy popcorn smile to the towel draped over the busboy’s pumped-up forearm to a medium shot of exicted Secret Service men to a close-up of a finger cramped on a trigger.” Or “imagine an Eisenstein montage of calendar pages flying through the air like angry birds, my face intercut with a baby carriage rocking down a staircase.”

DB: Well it very much is a tribute to cinema and it’s also exploring the question of where does the self exist with all this input, right?

Dodie Bellamy’s writing focuses on sexuality, politics, and narrative experimentation, challenging the distinctions between fiction, essay, and poetry. Her latest books are Bee Reaved and a new edition of The Letters of Mina Harker, both from Semiotext(e). She was the 2018-19 subject of the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art’s On Our Mind program, a year-long series of public events, commissioned essays, and reading group meetings inspired by an artist’s writing and lifework. With Kevin Killian she edited for Nightboat Books Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997. More info at www.belladodie.com.