The elm, the oak, the deer,

and the City of the wicked.

Photographs by Courtney Stephens

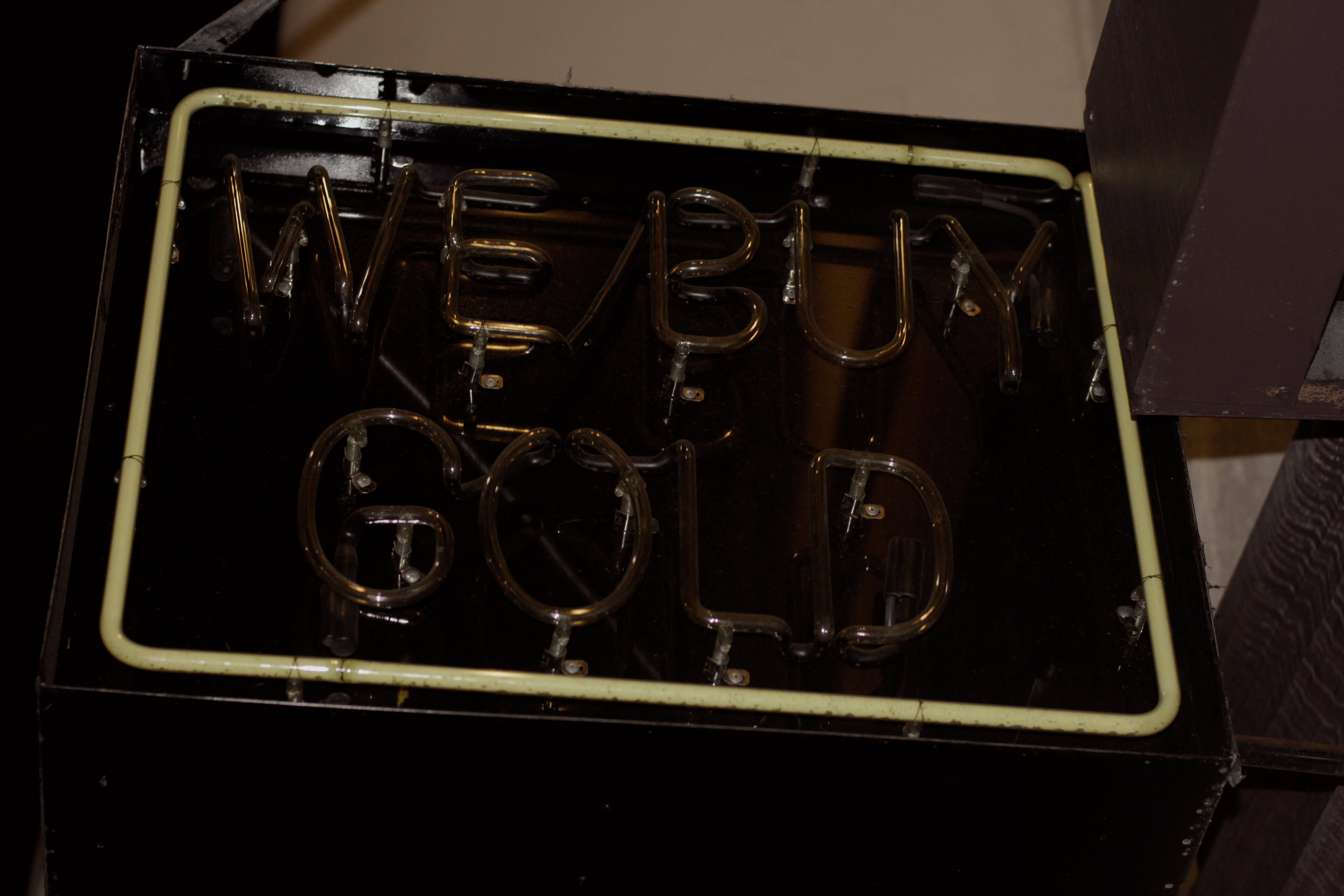

The following passages are excerpted from Pierre Klossowski’s Diana at her Bath, a collection of writings about the myth of Diana and Acteon. I have chosen passages in which Klossowski envisions Diana’s relationship with her own, and the world’s, materiality and paired them with images from the empty sidewalks and shuttered window vitrines of Hollywood Boulevard.

The cyclops provided Diana with her bow and arrow.

Did he not thereby trigger in her the cruel principle of her virginity?

Did he not thereby trigger in her the cruel principle of her virginity?

The “little people” saw in Diana an exceptional example of severity amidst the context of Olympian frivolity, and envisioned in her the grace of divine mercy, descended from an implacably serene sky: a tutelary deity of animal and vegetable life, favorable to betrothal as well as to the fecundity of wives, she formed healthy girls in her own image and was nonetheless “a lioness for women”; she loosed ravaging monsters across the countrysides of kingdoms hostile or indifferent to her altars, as the hunt became more and more a game than an economic necessity, as if to remind men that, being a sign of both the dark and serene aspects of the universe, she presided over her wholeness. Now in what respect did this wholeness coincide with her virginal nature, correspond to her chastity? Why did she renounce the emotions that animate the universe? Was she hiding, from the gods as well as the mortals, her other face eternally?

Diana, like the other goddesses, plays her part as woman to the full. Diana washes herself like the other goddesses; but she has never been known to eat the animals she kills. Diana washes herself after the hunt: not, however, out of the need to clean herself of the sweat and earthen dust covering her body... Diana is cleansing herself of the blood spilled, of her contact with blind forces, earthly needs: she is cleansing herself of a useful activity; in the pool she recovers her principle of useless serenity.

The moment the gods assume a body of their own, they care for it, and have fun caring for it, experiencing the body’s needs rather than experiencing them directly. They do it out of deference to humanity.

When one has chosen the space in which to hunt unconscious creatures, such as big game — wild boars, bears, stags, which are but entities of needs in which sensations of satisfaction and fear alternate — one must limit and localize oneself inside lithe, agile forms, subjecting oneself to the conditions of all moving bodies capable of running into other bodies and sustaining countershocks. One submits to their heaviness as much as one gains from their flexibility, and in turn one comes to know fatigue and the need for rest after the excitement. And although, as a deity, one is impassive, one accepts as well the inconvenience or amusement of being seen as a goddess. You do not allow the prey the time to see you in any case, the prey knows you and fears you.

Diana tests her silver bow four times; she tests it against four objects: the first time against an elm; the second time against an oak; the third time against a deer; the fourth time against a City of the wicked.

Here, it appears, we see Diana occupying the three realms: in the sense that being herself the spiritual realm — the Archer, bearer of light — she manifests affinities with the three realms, but only through the mediation of the mineral (the silver bow) with which she maintains a secret affinity; and as this affinity extends to the vegetable realm in the forms of the elm and the oak, and to animal bestiality in the form of the deer, the investigation should end there. Can one actually classify the City of the wicked in the animal kingdom? Who would dare?

Diana’s fourth and last act, the fourth and last arrow which she reserves for the city, would therefore indicate a going beyond the three realms she wishes to integrate into herself: and here she seems to demarcate a fourth realm with which, however, she manifests a negative affinity. For just as her silver bow, in the first movement, signified her positive affinity with the mineral realm in its highest and transcendent sense, so now in the last movement, the fourth, Diana indicates an affinity between animal bestiality and the psychic, as well as the contradictory affinity of the psychic with the spiritual, in the form of wickedness.

If one considers that the silver bow, which is identical to the lunar crescent and thus an emblematic image of the goddess, serves here as an instrument for the exercise of divine power, and that in this operation, this instrument itself is put to the test, it becomes clear that, as silver (mineral realm) plays an active and transcendent role in relation to the other two realms (vegetable and animal), its highest role is fulfilled in the moral domain: the City of the wicked whose disintegrating character immediately evokes the function, in Art, of the spirit of sal ammoniac. For “a bit of mercury thrown into a solution of silver by spirits of sal ammoniac attracts the silver and divides it up into the branches and foliage that represent Diana’s tree.” Thus the silver bow and the City of the wicked or, more simply, of wickedness (that other mineral), are situated, in their relation to one another, in one same spiritual region — since Diana’s arrow shot must cross the three realms in order to strike its ultimate target.

Look not at Diana face to face, or you will vanish under her gaze. For if her entire body is visible, it is I myself who envelop her essence; only her gaze I cannot veil: for the rest of you, it means death. On the other hand, contemplate her askance, if you can, or in profile, but preferably from behind. Not that she cannot see you — far be it from me to entertain such folly, but though she might peer at you over her shoulder, she will tolerate you at her back. And who knows, she might just have to suffer you there; for it is through me that she conspires to appear, through me, whose body she has borrowed, that she must make shift and in this union take on, despite her pretentious impassivity, the impulses that spur me and are therefore my own.... If she is forever running — and here the chase is but a pretext — it is only to forget the visible body I have lent to her.

Courtney Stephens is a non-fiction and experimental filmmaker based in Los Angeles. Her work has been exhibited at the Berlinale, the Museum of Modern Art, New York Film Festival, The National Gallery of Art, and elsewhere.