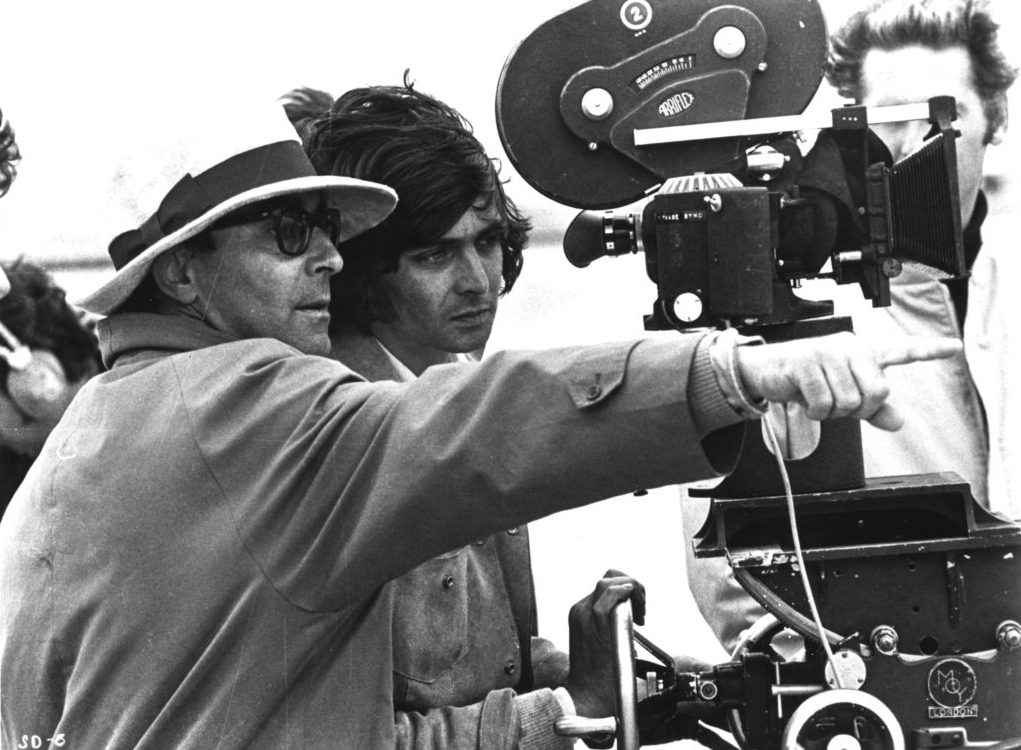

Cinematographer Anthony Richmond

Interview by Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Thomas: Your career as a cinematographer is incredible — you’ve worked on so many interesting films it’s hard to know where to begin. But since this will appear in the Halloween issue, I thought we could talk about some horror movies?

Tony Richmond: I like horror, it’s fantastic.

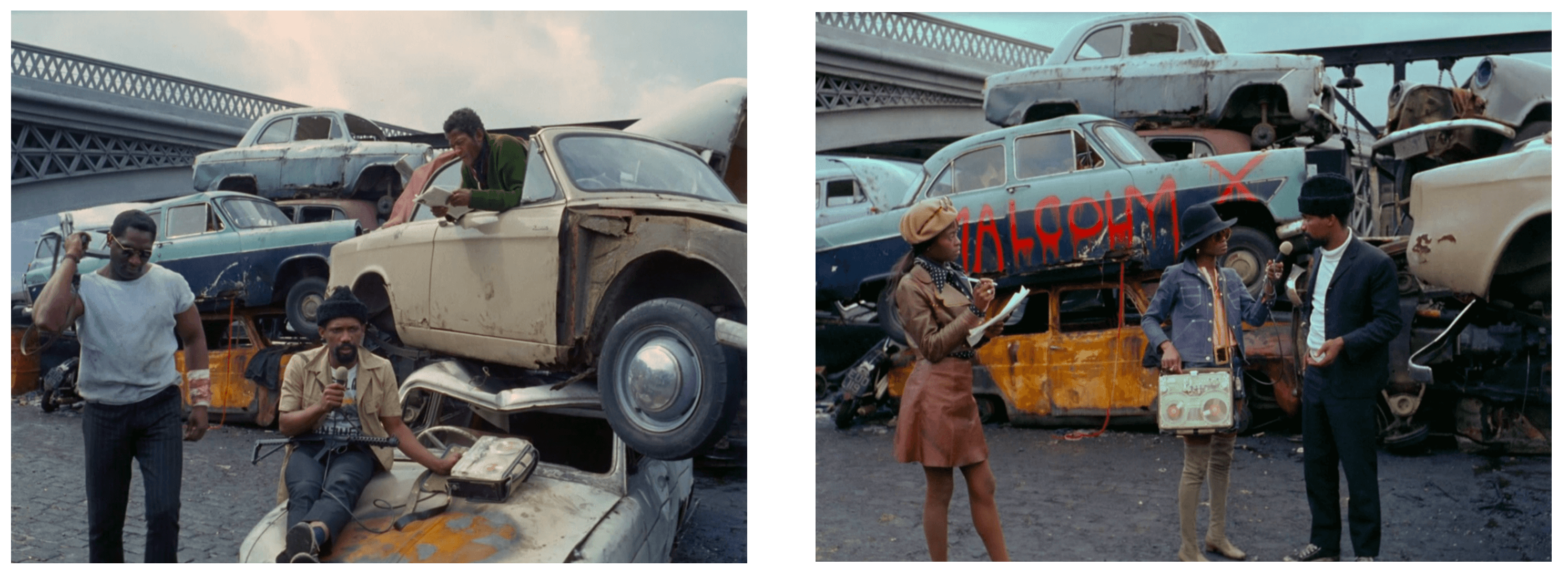

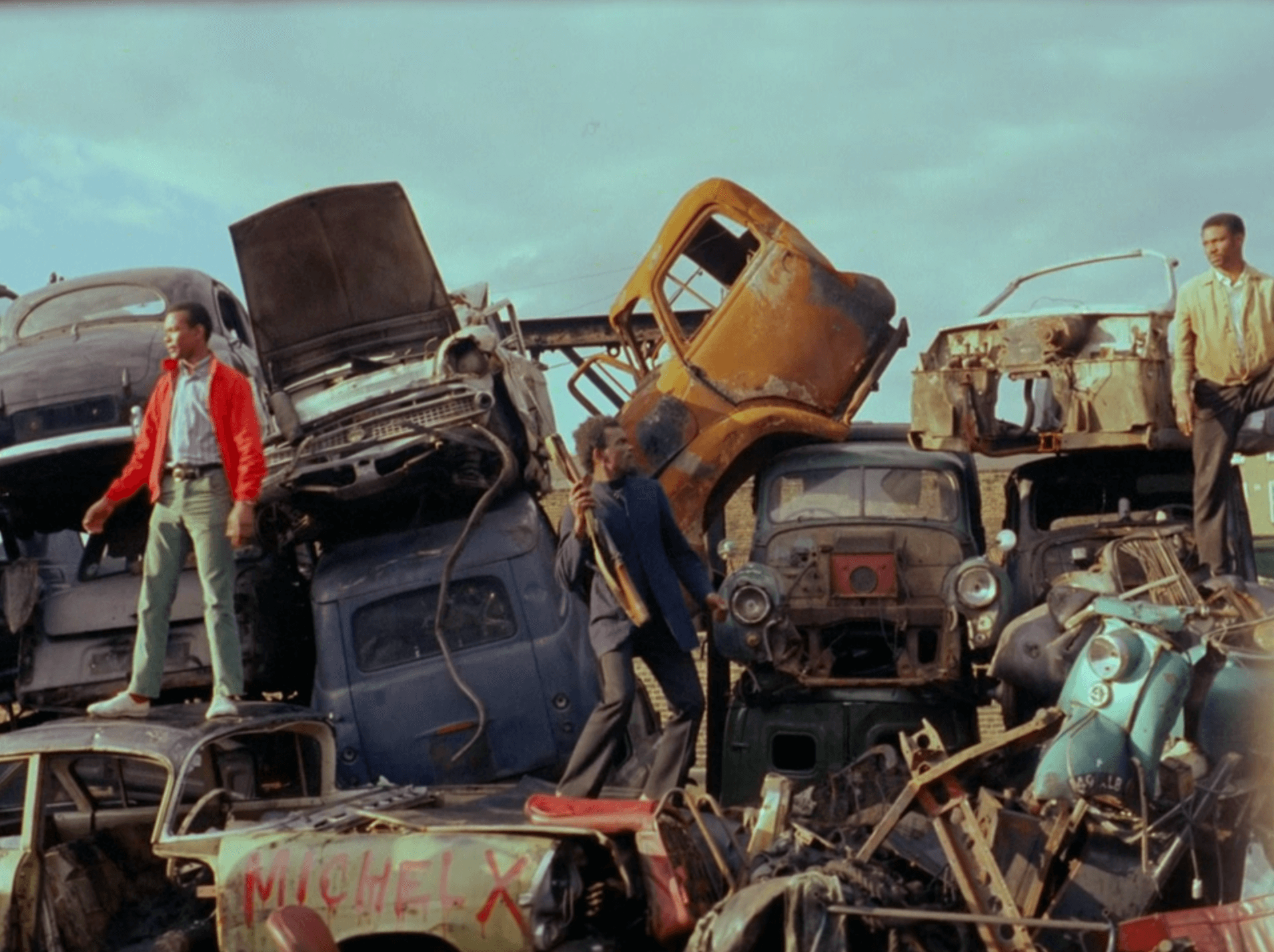

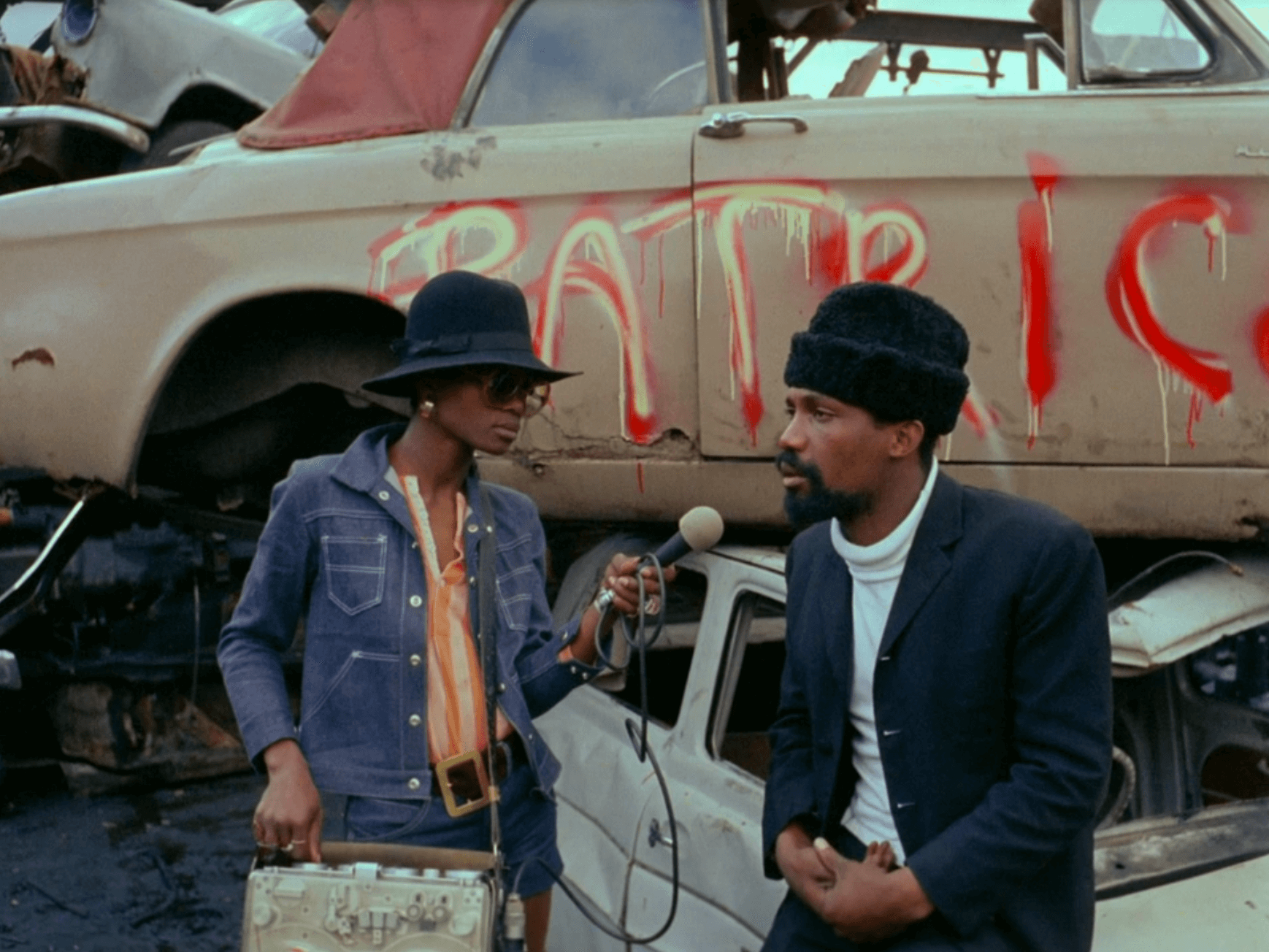

JT: Is it fair to begin with the voice of the devil? It’s not exactly horror but in June 1968, when you were 25 years old, Jean-Luc Godard asked you to be the Director of Photography on One Plus One, his first film outside of France. One Plus One documents The Rolling Stones in the process of constructing “Sympathy for the Devil” — one of the great rock and roll songs of the era — alongside episodes of political theater featuring the British Black Panthers and sequences featuring Anne Wiazemsky of Robert Bresson’s Au hassard Balthazar playing “Eve Democracy.” Can you please tell the story of how you got involved in this project? How did you first meet Godard?

Tony Richmond: I like horror, it’s fantastic.

JT: Is it fair to begin with the voice of the devil? It’s not exactly horror but in June 1968, when you were 25 years old, Jean-Luc Godard asked you to be the Director of Photography on One Plus One, his first film outside of France. One Plus One documents The Rolling Stones in the process of constructing “Sympathy for the Devil” — one of the great rock and roll songs of the era — alongside episodes of political theater featuring the British Black Panthers and sequences featuring Anne Wiazemsky of Robert Bresson’s Au hassard Balthazar playing “Eve Democracy.” Can you please tell the story of how you got involved in this project? How did you first meet Godard?

TR: Well it was a very weird experience. I was sitting at home in London, and I got a phone call one afternoon. A woman said, “My name is Eleni Collard, and I’m going to produce a film. I’d like to talk to you about it. Are you available?” I said yes. “Will you meet me tonight, outside the Hilton Hotel?” I said yes. So I got to the Hilton Hotel early, at 7 o’clock, you know, and I was watching cars coming in and out, just standing out there. Suddenly this huge limousine pulled up. One of those big ones, like the Queen has, with the crest on the side and the flags. And the door opens and this voice said, “Mr. Richmond?” I said yes. And she says, “Please get in.” So I got in and we started to drive around London and she proceeded to talk but she didn’t say anything about the film. Thank god there was a bar in the Rolls, with glasses of cognac. But she wasn’t saying anything about the movie. Then we ended up in Cheyne Walk, got out, knocked on the door, you know, and it was Mick Jagger’s house. We went up the stairs, and as I was getting close to the top of the stairs you could smell the pot, or the hash, or whatever it was wafting through the air. So I walked in, and there were The Rolling Stones laying around in various states of whatever, on the floor, strumming some instruments, and Jean-Luc Godard was sitting in the corner. I was just absolutely shocked.

His assistant came over, took me over to introduce me and said, “Excuse me, Jean-Luc,” and we just starting talking and talking and talking. Then he said, “Well I’ve gotta go now,” and he got up and left. His assistant came over and said, “Okay, Jean-Luc wants you to do it. He wants you to go to Paris every weekend for three weeks to discuss how we’re going to shoot the movie.” So the next weekend —

JT: So wait, was this was shot in June of 1968? Are you having these conversations in May 68 in Paris?

TR: Probably that early. It was just a few weeks before we started shooting.

JT: A lot was happening in May 68 in Paris!

TR: This was before the student riots. I know that for a fact. So I go out there on a late plane on a Friday night, check into a very nice hotel, and they say, “Godard will ring.” So I didn’t leave the hotel. I didn’t go out Friday night, had dinner in the room. Had breakfast in the room Saturday. Didn’t hear from him. Had dinner in the room again Saturday night. Finally on Sunday, at about 2pm in the afternoon, he called me and I went over to his apartment.

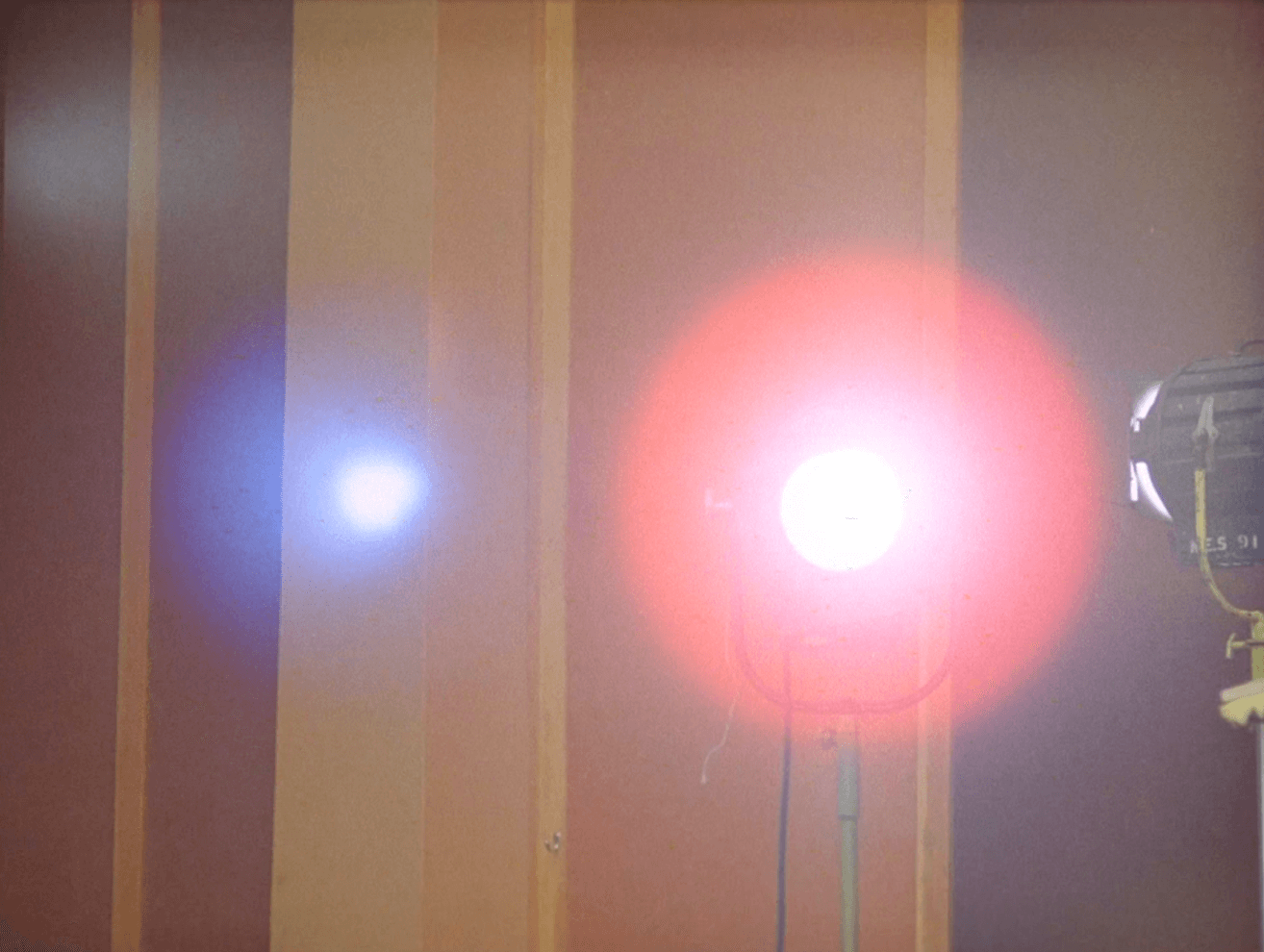

He basically wanted to know how we were going to shoot the Stones sequences, because he had seen the Barnes recording studio. Barnes is a difficult place because it used to be a cinema, before they turned it into a recording studio, so the ceilings were really high which made it almost impossible to rig. So what he wanted me to do, since the Stones were going to be in there, was to go back and shoot some tests on various black-and-white films, very high-speed stock, and see what we could do. It was all going to be black-and-white. What he was intending to do was to put color washes on them, as he had done in other films.

So I went in and did some tests and did some very interesting stuff. It was quite extraordinary. We used sound recording stock, which is very very fast. So it didn’t need much light, and they produced some extraordinary images. But while I was there, I thought, you know, I think I could do a little thing here. So I got some battens and put them up in the ceiling — they had these big high ladders — and I just lit a little area in color. Then I went back to Paris the following week and showed it to Godard, and he said, “Can you do the whole studio like that?” I said yes, and that’s how it became color rather than black-and-white.

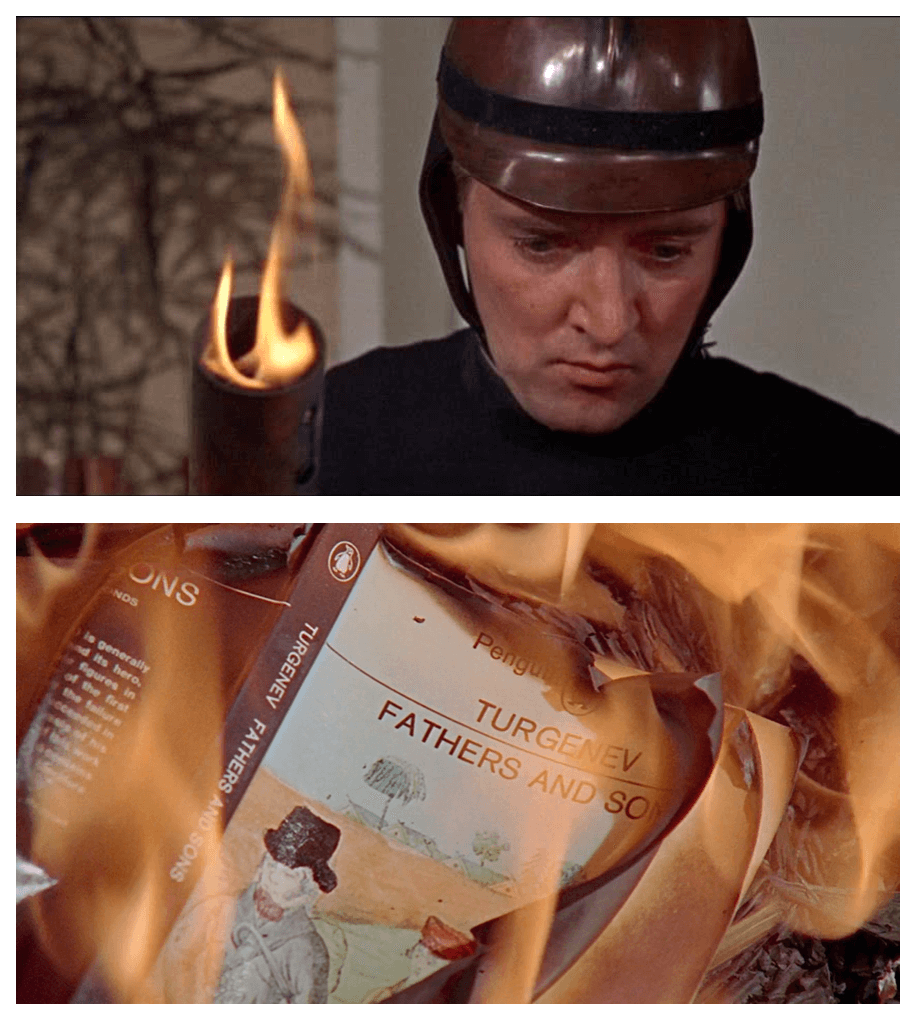

JT: To step back for a sec, before you shot Godard’s One Plus One you actually pulled focus on François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966).

His assistant came over, took me over to introduce me and said, “Excuse me, Jean-Luc,” and we just starting talking and talking and talking. Then he said, “Well I’ve gotta go now,” and he got up and left. His assistant came over and said, “Okay, Jean-Luc wants you to do it. He wants you to go to Paris every weekend for three weeks to discuss how we’re going to shoot the movie.” So the next weekend —

JT: So wait, was this was shot in June of 1968? Are you having these conversations in May 68 in Paris?

TR: Probably that early. It was just a few weeks before we started shooting.

JT: A lot was happening in May 68 in Paris!

TR: This was before the student riots. I know that for a fact. So I go out there on a late plane on a Friday night, check into a very nice hotel, and they say, “Godard will ring.” So I didn’t leave the hotel. I didn’t go out Friday night, had dinner in the room. Had breakfast in the room Saturday. Didn’t hear from him. Had dinner in the room again Saturday night. Finally on Sunday, at about 2pm in the afternoon, he called me and I went over to his apartment.

He basically wanted to know how we were going to shoot the Stones sequences, because he had seen the Barnes recording studio. Barnes is a difficult place because it used to be a cinema, before they turned it into a recording studio, so the ceilings were really high which made it almost impossible to rig. So what he wanted me to do, since the Stones were going to be in there, was to go back and shoot some tests on various black-and-white films, very high-speed stock, and see what we could do. It was all going to be black-and-white. What he was intending to do was to put color washes on them, as he had done in other films.

So I went in and did some tests and did some very interesting stuff. It was quite extraordinary. We used sound recording stock, which is very very fast. So it didn’t need much light, and they produced some extraordinary images. But while I was there, I thought, you know, I think I could do a little thing here. So I got some battens and put them up in the ceiling — they had these big high ladders — and I just lit a little area in color. Then I went back to Paris the following week and showed it to Godard, and he said, “Can you do the whole studio like that?” I said yes, and that’s how it became color rather than black-and-white.

JT: To step back for a sec, before you shot Godard’s One Plus One you actually pulled focus on François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966).

TR: I was the clapper boy, but I began to pull focus on Fahrenheit 451.

JT: That was Truffaut’s first film in color.

TR: That’s right, and his first outside of France, I believe. He was a wonderful man, Truffaut. Absolutely wonderful. Quite a gentle man. I’ll always remember there was one scene in the movie where Julie Christie was crying, and he wanted to know why she was crying, he didn’t understand that. He was just gentle, and I really liked him.

JT: So you saw that, as a director, he stepped aside with Julie Christie and asked why she was crying?

TR: He didn’t want crying in that scene, but he was very gentle with her, you know. Some of that stuff in Fahrenheit 451 was very difficult to do, as opposed to what would be very simple today. Because you remember in the apartment, it was all big screens.

JT: That was Truffaut’s first film in color.

TR: That’s right, and his first outside of France, I believe. He was a wonderful man, Truffaut. Absolutely wonderful. Quite a gentle man. I’ll always remember there was one scene in the movie where Julie Christie was crying, and he wanted to know why she was crying, he didn’t understand that. He was just gentle, and I really liked him.

JT: So you saw that, as a director, he stepped aside with Julie Christie and asked why she was crying?

TR: He didn’t want crying in that scene, but he was very gentle with her, you know. Some of that stuff in Fahrenheit 451 was very difficult to do, as opposed to what would be very simple today. Because you remember in the apartment, it was all big screens.

They weren’t television, it was all back projection, and it was very complicated to do that. It was just wonderful and Truffaut was great, but still, Godard was my favorite director.

JT: So you went to Paris to visit Godard, to begin the conversations. What did he say?

TR: He wanted me to operate the camera. In those days you had a union, so you had a DP, camera operator, focus puller, and clapper boy, and he made it quite clear he wanted me as DP to operate the camera myself, he didn’t want another operator. And that was it.

JT: In One Plus One you were shooting very long takes, with evolving compositions.

TR: There’s a reason for that. We shot at Barnes Recording Studios. The Stones were actually recording “Sympathy for the Devil.” They weren’t doing it for us. That’s why we had to do these long takes, so as not to interrupt them. So basically what I did is put all these 8x4 sheets of plywood on the floor. When we got there in the morning — you never knew when The Stones were going to turn up — and we always knew where the boys were going to be, because Glyn Johns, the engineer, and his assistant would set up the sound baffles, so we always knew where Mick was going to be, where Keith was going to be, Charlie, Brian. That’s all we knew. What we did is we used what’s called an Elemack Dolly, which is a little four-wheel dolly which doesn’t really go up and down. I operated, had a focus-puller, and Tony Tucker, my Grip, and Jean-Luc Godard. What would happen is Jean-Luc Godard would say “track,” and we would track, and then he would tell the dolly grip to stop — and I would find an image, not knowing what I was going to find.

JT: Had you been a camera operator before that?

TR: You know I was never a camera operator. I had been a clapper boy for about six years, or a second assistant camera as they’re called now. And then I pulled focus. I started pulling focus on B Camera on Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, and then after that I pulled focus on Casino Royale, where David Niven was James Bond, and then I pulled focus on Far From the Maddening Crowd. It was John Schlesinger who gave me my break as a DP. I was very young, 23 or 24, and that was absolutely unheard of in those days. So the establishment used to call me “the clapper’s lighter,” because in those days we were known as “lighting cameramen” — the establishment were very pissed off, and so I pissed them off even more and went out and bought myself a Bentley.

JT: Schlesinger spotted your potential. Your career from the beginning is pretty incredible. I mean in May 1968 you’re working with Jean-Luc Godard and The Rolling Stones.

TR: I had a lot of luck. I shot my first feature in 1967, which was a very big caper movie called Only When I Larf (1968), with David Hemmings, who was a monster-star then.

JT: You said you were a clapper and maybe you pulled focus a little bit, but how did you learn how to light?

TR: I watched. In those days you’d shoot all day long. Then the next day, if you’re in the studio, at lunchtime you go to see the dailies of the day before. You didn’t work anywhere near as fast as we work now, so you could ask people questions. I learned to light by watching other people. John Wilcox, a truly great DP who never got his just dues, although he shot some great movies, and Freddie Young, and Nic Roeg. I’d watch them light and then I’d see the dailes. It was great camaraderie. As I’d say, you’d go to see dailies at lunchtime, or if you were out shooting you’d go to the lab and see them in the evening, and they had beer and sandwiches there. It was a wonderful thing. And that all stopped when digital came in, because then what would happen, to save money, is they’d transfer the dailies to DVDs and give everyone DVDs which looked like shit, so the business has changed. Nobody gives a shit anymore. But I have to tell you, I had the best of times, because you have a lot of fun making movies. There’s a lot of laughter, and nowadays it's just miserable.

JT: So you shot a big caper movie, as Director of Photography.

TR: Yes and then I did another picture straight after that with Bette Davis.

JT: Bette Davis??

TR: It was quite extraordinary. She had to approve of the DP, as big movie stars did in those days, and then she found out how old I was and she said “That’s not possible. What has he done?” So she said she didn’t want me, apparently, and they said, “Well when you come over, let him do your make-up tests.” So she came over and we went into Pinewood Studios, on a small set, and I shot these make-up tests. The next day we were going to have lunch — the director David Greene and I, and Julian Wintle the producer, and Bette Davis — “Bett Davis” — and we were going to go after lunch to the screening room. So what I did is, we shot these tests, and sent them to the lab for the next morning. I knew the head of the lab there and so I said, “Can I come in at 5 o’clock and color correct these?” And they said yes. So we color corrected them, they made a new print, and I took it with me back to the studios. I said I’ve got the print, let’s take a look at it. I was sitting a row behind her, and when she saw the tests and the lights went up — everyone was fucking quiet — she turned to me and said, “Well, Mr. Richmond. What on earth do you think of these?” I said, “Well Ms. Davis, may I speak to you honestly?” “YES you can.” I said, “It is not my photography, it’s your make-up.” And she said, “What, I’ve had this make-up man for 15 years,” blah blah blah. And I said, “Well I’m very sorry. It’s not good.” And she said, “What do you suggest?” (Now my first wife was a very good make-up artist and she used to work with a guy called Douggie Webb. Doug Webb was the head of Max Factor in London, for theatrical make-up.) I said “Madame Sin” — her character’s name was Madame Sin — “Madame Sin needs a make-up design for her. And I would like to take you tomorrow morning to Max Factor in London for him to design your make-up.” And she agreed.

So we went down there and she gets in the chair and he puts the smock around her and he starts with the brush. Now he deals with everybody, this guy. Big theater actors. So he’s not at all interested in movie actors

JT: But Bette Davis was a very big movie star.

TR: She was HUGE, a HUGE star. So Douggie started, and she started to criticize, and he said, “Ms. Davis, please. Do not criticize my work until I have finished.” And that shut her up, and she loved it. So now I’ve got the job, and another funny thing happened. There were three very big photographers in London at the time. There was David Bailey, who you’ve probably heard of, Brian Duffy, and Terry Donovan. I had shot some commercials for Terry and we were having lunch one day and I say, “What the fuck am I going to do with this old bag? She’s going to be on my back.” And he said, “Listen, I’ll give you a bit of advice. Get the carpenters to make up a nice box. Get it veneered and lacquered, and put a nice lock on it. And just put a big black BD filters on top of it. Wherever you go on the set, have your assistant walk with you. And when you’re near her, put that box down. She’ll notice it.” So on about the second day of shooting — she continued to call me Mr. Richmond — she said, “Mr. Richmond, what is in that box?” And I said “Filters, Ms. Davis.” And she said, “Why does it say BD filters?” I said, “They’re your filters, maam.” She said “They’re all for me?” I said, “Yes maam.” She said, “I think you should call me Bette.” It was a fantastic experience. She was wonderful. In the end, she loved me.

JT: So you went to Paris to visit Godard, to begin the conversations. What did he say?

TR: He wanted me to operate the camera. In those days you had a union, so you had a DP, camera operator, focus puller, and clapper boy, and he made it quite clear he wanted me as DP to operate the camera myself, he didn’t want another operator. And that was it.

JT: In One Plus One you were shooting very long takes, with evolving compositions.

TR: There’s a reason for that. We shot at Barnes Recording Studios. The Stones were actually recording “Sympathy for the Devil.” They weren’t doing it for us. That’s why we had to do these long takes, so as not to interrupt them. So basically what I did is put all these 8x4 sheets of plywood on the floor. When we got there in the morning — you never knew when The Stones were going to turn up — and we always knew where the boys were going to be, because Glyn Johns, the engineer, and his assistant would set up the sound baffles, so we always knew where Mick was going to be, where Keith was going to be, Charlie, Brian. That’s all we knew. What we did is we used what’s called an Elemack Dolly, which is a little four-wheel dolly which doesn’t really go up and down. I operated, had a focus-puller, and Tony Tucker, my Grip, and Jean-Luc Godard. What would happen is Jean-Luc Godard would say “track,” and we would track, and then he would tell the dolly grip to stop — and I would find an image, not knowing what I was going to find.

JT: Had you been a camera operator before that?

TR: You know I was never a camera operator. I had been a clapper boy for about six years, or a second assistant camera as they’re called now. And then I pulled focus. I started pulling focus on B Camera on Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, and then after that I pulled focus on Casino Royale, where David Niven was James Bond, and then I pulled focus on Far From the Maddening Crowd. It was John Schlesinger who gave me my break as a DP. I was very young, 23 or 24, and that was absolutely unheard of in those days. So the establishment used to call me “the clapper’s lighter,” because in those days we were known as “lighting cameramen” — the establishment were very pissed off, and so I pissed them off even more and went out and bought myself a Bentley.

JT: Schlesinger spotted your potential. Your career from the beginning is pretty incredible. I mean in May 1968 you’re working with Jean-Luc Godard and The Rolling Stones.

TR: I had a lot of luck. I shot my first feature in 1967, which was a very big caper movie called Only When I Larf (1968), with David Hemmings, who was a monster-star then.

JT: You said you were a clapper and maybe you pulled focus a little bit, but how did you learn how to light?

TR: I watched. In those days you’d shoot all day long. Then the next day, if you’re in the studio, at lunchtime you go to see the dailies of the day before. You didn’t work anywhere near as fast as we work now, so you could ask people questions. I learned to light by watching other people. John Wilcox, a truly great DP who never got his just dues, although he shot some great movies, and Freddie Young, and Nic Roeg. I’d watch them light and then I’d see the dailes. It was great camaraderie. As I’d say, you’d go to see dailies at lunchtime, or if you were out shooting you’d go to the lab and see them in the evening, and they had beer and sandwiches there. It was a wonderful thing. And that all stopped when digital came in, because then what would happen, to save money, is they’d transfer the dailies to DVDs and give everyone DVDs which looked like shit, so the business has changed. Nobody gives a shit anymore. But I have to tell you, I had the best of times, because you have a lot of fun making movies. There’s a lot of laughter, and nowadays it's just miserable.

JT: So you shot a big caper movie, as Director of Photography.

TR: Yes and then I did another picture straight after that with Bette Davis.

JT: Bette Davis??

TR: It was quite extraordinary. She had to approve of the DP, as big movie stars did in those days, and then she found out how old I was and she said “That’s not possible. What has he done?” So she said she didn’t want me, apparently, and they said, “Well when you come over, let him do your make-up tests.” So she came over and we went into Pinewood Studios, on a small set, and I shot these make-up tests. The next day we were going to have lunch — the director David Greene and I, and Julian Wintle the producer, and Bette Davis — “Bett Davis” — and we were going to go after lunch to the screening room. So what I did is, we shot these tests, and sent them to the lab for the next morning. I knew the head of the lab there and so I said, “Can I come in at 5 o’clock and color correct these?” And they said yes. So we color corrected them, they made a new print, and I took it with me back to the studios. I said I’ve got the print, let’s take a look at it. I was sitting a row behind her, and when she saw the tests and the lights went up — everyone was fucking quiet — she turned to me and said, “Well, Mr. Richmond. What on earth do you think of these?” I said, “Well Ms. Davis, may I speak to you honestly?” “YES you can.” I said, “It is not my photography, it’s your make-up.” And she said, “What, I’ve had this make-up man for 15 years,” blah blah blah. And I said, “Well I’m very sorry. It’s not good.” And she said, “What do you suggest?” (Now my first wife was a very good make-up artist and she used to work with a guy called Douggie Webb. Doug Webb was the head of Max Factor in London, for theatrical make-up.) I said “Madame Sin” — her character’s name was Madame Sin — “Madame Sin needs a make-up design for her. And I would like to take you tomorrow morning to Max Factor in London for him to design your make-up.” And she agreed.

So we went down there and she gets in the chair and he puts the smock around her and he starts with the brush. Now he deals with everybody, this guy. Big theater actors. So he’s not at all interested in movie actors

JT: But Bette Davis was a very big movie star.

TR: She was HUGE, a HUGE star. So Douggie started, and she started to criticize, and he said, “Ms. Davis, please. Do not criticize my work until I have finished.” And that shut her up, and she loved it. So now I’ve got the job, and another funny thing happened. There were three very big photographers in London at the time. There was David Bailey, who you’ve probably heard of, Brian Duffy, and Terry Donovan. I had shot some commercials for Terry and we were having lunch one day and I say, “What the fuck am I going to do with this old bag? She’s going to be on my back.” And he said, “Listen, I’ll give you a bit of advice. Get the carpenters to make up a nice box. Get it veneered and lacquered, and put a nice lock on it. And just put a big black BD filters on top of it. Wherever you go on the set, have your assistant walk with you. And when you’re near her, put that box down. She’ll notice it.” So on about the second day of shooting — she continued to call me Mr. Richmond — she said, “Mr. Richmond, what is in that box?” And I said “Filters, Ms. Davis.” And she said, “Why does it say BD filters?” I said, “They’re your filters, maam.” She said “They’re all for me?” I said, “Yes maam.” She said, “I think you should call me Bette.” It was a fantastic experience. She was wonderful. In the end, she loved me.

So there was a lot of fun. Nikes had just come out in England — you know the first running shoes or whatever you call them. I had a pair, they were big and heavy, and she said, “What are those shoes you’re wearing?” I said “They’re running shoes.” She said, “Why would you wear running shoes to work? And I said, “To run away from you if you don’t like what I’m doing!”

Basically it was a movie of the week for CBS but a feature for the rest of the world, so we had quite a decent budget. We spent six weeks in Pinewood Studios and then we went to the Isles of Scotland for maybe ten weeks. We all stayed in the same hotel, but where we were shooting was quite a way from the hotel. We had a helicopter with us, since there was a lot of helicopter stuff, and I chose the pilot.

JT: For helicopter shots in the Bette Davis movie?

TR: Yes. What would happen is she would drive to the set, which was about an hour on the other part of the island, and we decided — this is a horrible way to shoot, but what we decided was to shoot all of her close-ups first, before the make-up would wear off, you know? So David Greene and I used to fly to work in the helicopter, and then we’d shoot with her, and then she’d drive back and we’d continue shooting, and then the helicopter would fly us back. You could do all sorts of shit in those days. It would land on the grounds of the hotel. And she would hear the helicopter coming. And she’d be outside, with a waiter with a silver tray with two glasses of Scotch, one for David and one for me. Because she drank a lot. And then when we were back at Pinewood Studios, after dailies, I would go to her room and we would sit there drinking for a couple of hours. She was lovely. She gave me a beautiful gift. She gave me one of those fold-up chairs, a little thing that looks like an umbrella with three legs, which you sit on. She said “You know, you need to sit down. You’re always on your feet.” So I’ve got that beautiful chair, signed by her. She was lovely. I’ve had a very extraordinary career. I’ve been very lucky. And that I ended up with Godard. Still to this day that was the highlight of my career, because I was just a huge Godard fan.

JT: So let’s go back to One Plus One. 1968 was chaotic, and had its tragedies. Just a month or two before you started making the film, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. And in June, as you were in production, Robert Kennedy was assassinated here in Los Angeles. He had just won the Democratic primaries and was a presidential candidate in the 1968 election. So when Jagger sings “I shouted out / Who killed the Kennedys?” — putting it in the plural — this was responsive to the immediate moment.

TR: Yes, he changed it. And the other thing was, going back to what was happening in Paris at the time, we did about four nights in the studio with The Stones. And what I’d done is that I had put all these battens across overhead, with hundreds and hundreds of photofloods in pretty hot bulbs, and covered them with tracing paper, to give it a soft overall top light, and a few lights in the shot, which he didn’t mind.

Basically it was a movie of the week for CBS but a feature for the rest of the world, so we had quite a decent budget. We spent six weeks in Pinewood Studios and then we went to the Isles of Scotland for maybe ten weeks. We all stayed in the same hotel, but where we were shooting was quite a way from the hotel. We had a helicopter with us, since there was a lot of helicopter stuff, and I chose the pilot.

JT: For helicopter shots in the Bette Davis movie?

TR: Yes. What would happen is she would drive to the set, which was about an hour on the other part of the island, and we decided — this is a horrible way to shoot, but what we decided was to shoot all of her close-ups first, before the make-up would wear off, you know? So David Greene and I used to fly to work in the helicopter, and then we’d shoot with her, and then she’d drive back and we’d continue shooting, and then the helicopter would fly us back. You could do all sorts of shit in those days. It would land on the grounds of the hotel. And she would hear the helicopter coming. And she’d be outside, with a waiter with a silver tray with two glasses of Scotch, one for David and one for me. Because she drank a lot. And then when we were back at Pinewood Studios, after dailies, I would go to her room and we would sit there drinking for a couple of hours. She was lovely. She gave me a beautiful gift. She gave me one of those fold-up chairs, a little thing that looks like an umbrella with three legs, which you sit on. She said “You know, you need to sit down. You’re always on your feet.” So I’ve got that beautiful chair, signed by her. She was lovely. I’ve had a very extraordinary career. I’ve been very lucky. And that I ended up with Godard. Still to this day that was the highlight of my career, because I was just a huge Godard fan.

JT: So let’s go back to One Plus One. 1968 was chaotic, and had its tragedies. Just a month or two before you started making the film, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. And in June, as you were in production, Robert Kennedy was assassinated here in Los Angeles. He had just won the Democratic primaries and was a presidential candidate in the 1968 election. So when Jagger sings “I shouted out / Who killed the Kennedys?” — putting it in the plural — this was responsive to the immediate moment.

TR: Yes, he changed it. And the other thing was, going back to what was happening in Paris at the time, we did about four nights in the studio with The Stones. And what I’d done is that I had put all these battens across overhead, with hundreds and hundreds of photofloods in pretty hot bulbs, and covered them with tracing paper, to give it a soft overall top light, and a few lights in the shot, which he didn’t mind.

And on the last night we were due there, we were almost finished, and there was a big POP BANG and we looked up and one of the bulbs had exploded and caught the tracing paper on fire a little bit. I remember the guy’s name, Harry Jackson, he was the best boy, he went up the ladder with the fire extinguisher, and just as he got to the top, all these photofloods went BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG BANG like machine guns going off. The studio had caught fire.

JT: The Stones were there?

TR: Yeah, they were all stoned and they didn’t give a shit. But I sort of burned the studio down — eventually the fire brigade came, and what had happened, as we found out later, was that this recording studio had a whole load of sawdust up top, for the sound, and it had probably been smouldering for days. The firemen had to come in from the top. It was a nightmare. We all rushed outside. Godard was there and said “Listen, don’t say anything, but I’m going back to Paris tomorrow morning.” No one could find Godard.

JT: How long was he gone?

TR: I think he was gone for two weeks.

JT: And the production was on hiatus?

TR: The production was on hiatus and I was on payroll, which was good. They hired me out to Nicholas Ray to do some test footage.

JT: What? Nicholas Ray?

TR: Yeah, that was fun.

JT: What project?

TR: It was a test of some kind. I don’t remember what it was for, but I love Nicholas Ray.

JT: So did Godard. Did he know that you did that?

TR: Yeah, he did in the end. What would happen is a car would pick me up, and go pick Nick Ray up in his hotel.

JT: Had you known him previously?

TR: No. I had met him, but he would never have remembered me because that was when we were on Zhivago. He owned a bar in Madrid called Nick’s Bar. Nic Roeg and I used to go drinking there.

JT: Nick Ray owned a bar in Madrid?

TR: Yeah, Nicholas Ray. I used to go and pick him up, go to his hotel room and knock on the door and he would be there bandaging his legs, he had a bad ankle, and drinking Scotch out of a bottle at that time in the morning. But I love Nick Ray.

JT: So Godard returns to London...

TR: He came back, and we continued. He was very political, Godard. Very political. He was a communist, you know. And then all that stuff we did in London, I mean going around London and spraying all that stuff.

TR: Yeah, they were all stoned and they didn’t give a shit. But I sort of burned the studio down — eventually the fire brigade came, and what had happened, as we found out later, was that this recording studio had a whole load of sawdust up top, for the sound, and it had probably been smouldering for days. The firemen had to come in from the top. It was a nightmare. We all rushed outside. Godard was there and said “Listen, don’t say anything, but I’m going back to Paris tomorrow morning.” No one could find Godard.

JT: How long was he gone?

TR: I think he was gone for two weeks.

JT: And the production was on hiatus?

TR: The production was on hiatus and I was on payroll, which was good. They hired me out to Nicholas Ray to do some test footage.

JT: What? Nicholas Ray?

TR: Yeah, that was fun.

JT: What project?

TR: It was a test of some kind. I don’t remember what it was for, but I love Nicholas Ray.

JT: So did Godard. Did he know that you did that?

TR: Yeah, he did in the end. What would happen is a car would pick me up, and go pick Nick Ray up in his hotel.

JT: Had you known him previously?

TR: No. I had met him, but he would never have remembered me because that was when we were on Zhivago. He owned a bar in Madrid called Nick’s Bar. Nic Roeg and I used to go drinking there.

JT: Nick Ray owned a bar in Madrid?

TR: Yeah, Nicholas Ray. I used to go and pick him up, go to his hotel room and knock on the door and he would be there bandaging his legs, he had a bad ankle, and drinking Scotch out of a bottle at that time in the morning. But I love Nick Ray.

JT: So Godard returns to London...

TR: He came back, and we continued. He was very political, Godard. Very political. He was a communist, you know. And then all that stuff we did in London, I mean going around London and spraying all that stuff.

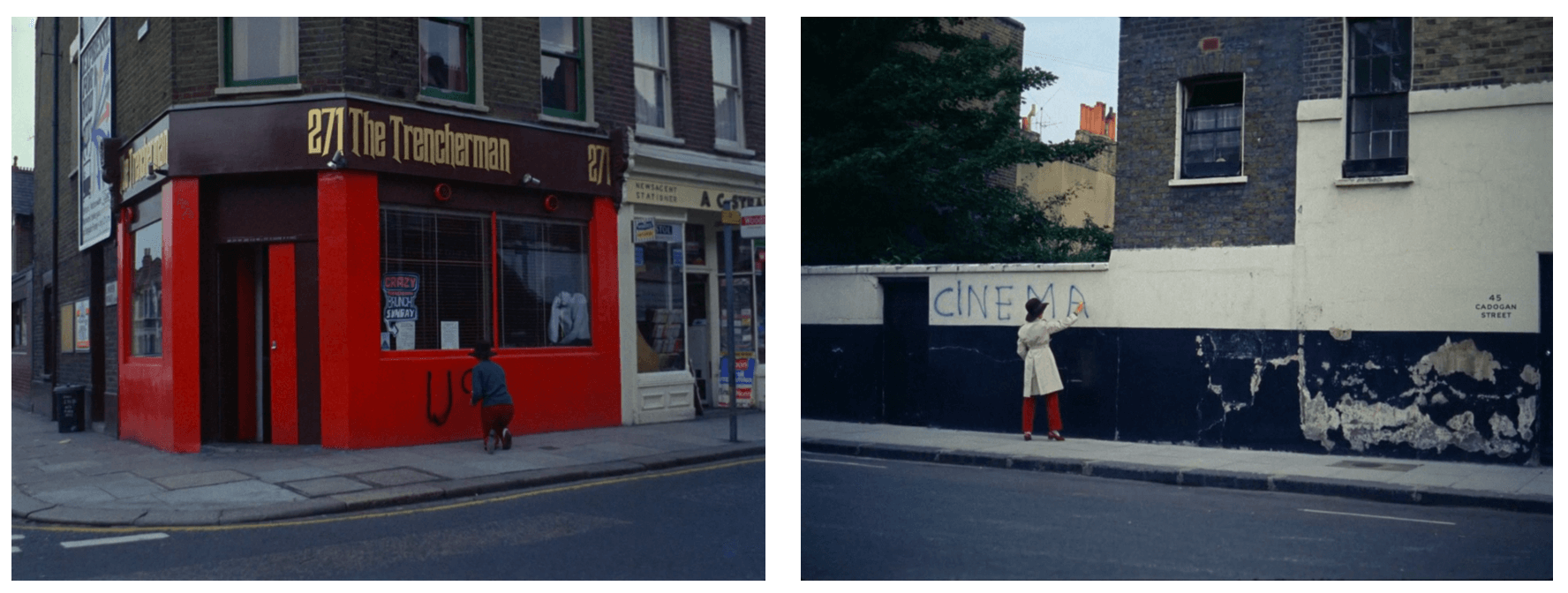

JT: Quite a few shots.

TR: A lot! We had no permissions. What would happen is — his car would pick me up in the morning and I would go to the hotel and he’d get in the car. He smoked these French cigarettes called Boyards, big big cigarettes with a big blue packet, and on the back of the packet he would write down what we would do that day. We’d arrange for the camera car to meet us in Hyde Park and then basically I’d take a handheld Arriflex, with no assistants or anything, and a few magazines, and we’d get in his limo and just drive around and he’d say stop. He’d say get down there [kneel with camera] and then Anne [Wiazemski] would run across the road and start spraying people’s cars. It was all real paint. Nobody gave a shit. And we went all over London like that.

JT: Do you remember these sequences?

TR: A lot! We had no permissions. What would happen is — his car would pick me up in the morning and I would go to the hotel and he’d get in the car. He smoked these French cigarettes called Boyards, big big cigarettes with a big blue packet, and on the back of the packet he would write down what we would do that day. We’d arrange for the camera car to meet us in Hyde Park and then basically I’d take a handheld Arriflex, with no assistants or anything, and a few magazines, and we’d get in his limo and just drive around and he’d say stop. He’d say get down there [kneel with camera] and then Anne [Wiazemski] would run across the road and start spraying people’s cars. It was all real paint. Nobody gave a shit. And we went all over London like that.

JT: Do you remember these sequences?

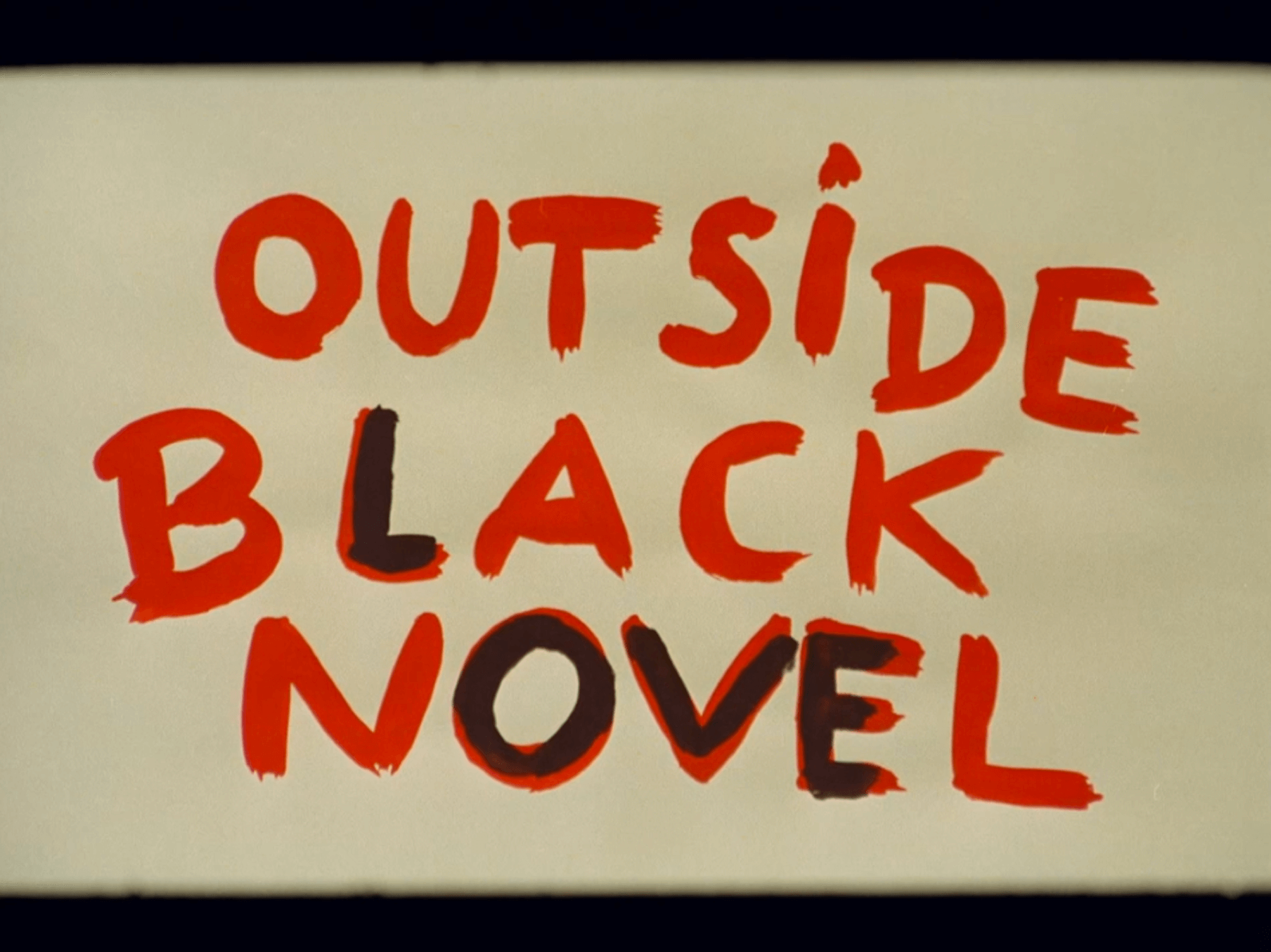

TR: Absolutely. You know a lot of people didn’t understand the movie, but I totally understood what was going on. It was about creation and destruction. The creation is The Rolling Stones and creation is never finished. Destruction is the English version of the Black Panthers, and that is never finished. On the political side, nothing has changed in America.

JT: It’s an incredible project. The people involved, the historical timing. The spirit of the movie as an experiment is very provisional. It’s in-process, not completed, and so Godard of course was furious when the producers put a different ending on his movie.

TR: That’s right.

JT: And Godard stormed the stage at the premiere?

TR: I was at the premiere. Godard hated the producers. Michael Pearson was Lord Cowdray’s son, who was one of the richest men in England at the time. He was producing the movie with an idiot called Iain Quarrier, who also plays a role in the bookshop. Godard didn’t like either Pearson or Quarrier, although he liked them enough to go and shoot on Lord Cowdray’s estate for the scene with Eve Democracy.

What had happened was — the movie is about creation and destruction, as we were saying, and neither of these is finished. At the end of the movie Godard had the Stones sort of sitting around strumming. Michael Pearson felt that, as they had paid for it, they should put the completed song of “Sympathy for the Devil” in the movie. And that drove Godard insane.

I was color correcting the movie in London, and I called him and said “The color correction is finished. It took me about five prints to get it right.” And he said, “How was the fourth print?” I said “It’s really good. Just a few minor tweaks.” And he said, “Any chance you can get that for me?” I said “Yeah, I can,” because I knew the head of the labs, so I called him (he was really helpful in my early career) and I said, “Can I have that print? Godard wants to see it.” So he says sure and I go and pick it up. I called Godard and said “I got it,” and he said, “Hold onto it. I’ll send someone to pick it up in couple of days time.” In a couple of days time a car comes around and picked the print up. So whilst we were at the premiere, just before it started, Godard ran down the aisle, jumped up on the stage, and knocked Iain Quarrier out sort of thing. He said, “This is not my film. My film is being screened outside.” He had arranged for projectors outside, and he wanted everybody to basically burn the theater down. But it was raining outside and everyone boo’d him and that was the end of that. But I felt very sorry for him, because he is a true auteur. One of the great New Wave directors, and they didn’t respect his wishes, and I was all for him. It really was the highlight of my career to work with Godard. He was my hero.

JT: It’s an incredible project. The people involved, the historical timing. The spirit of the movie as an experiment is very provisional. It’s in-process, not completed, and so Godard of course was furious when the producers put a different ending on his movie.

TR: That’s right.

JT: And Godard stormed the stage at the premiere?

TR: I was at the premiere. Godard hated the producers. Michael Pearson was Lord Cowdray’s son, who was one of the richest men in England at the time. He was producing the movie with an idiot called Iain Quarrier, who also plays a role in the bookshop. Godard didn’t like either Pearson or Quarrier, although he liked them enough to go and shoot on Lord Cowdray’s estate for the scene with Eve Democracy.

What had happened was — the movie is about creation and destruction, as we were saying, and neither of these is finished. At the end of the movie Godard had the Stones sort of sitting around strumming. Michael Pearson felt that, as they had paid for it, they should put the completed song of “Sympathy for the Devil” in the movie. And that drove Godard insane.

I was color correcting the movie in London, and I called him and said “The color correction is finished. It took me about five prints to get it right.” And he said, “How was the fourth print?” I said “It’s really good. Just a few minor tweaks.” And he said, “Any chance you can get that for me?” I said “Yeah, I can,” because I knew the head of the labs, so I called him (he was really helpful in my early career) and I said, “Can I have that print? Godard wants to see it.” So he says sure and I go and pick it up. I called Godard and said “I got it,” and he said, “Hold onto it. I’ll send someone to pick it up in couple of days time.” In a couple of days time a car comes around and picked the print up. So whilst we were at the premiere, just before it started, Godard ran down the aisle, jumped up on the stage, and knocked Iain Quarrier out sort of thing. He said, “This is not my film. My film is being screened outside.” He had arranged for projectors outside, and he wanted everybody to basically burn the theater down. But it was raining outside and everyone boo’d him and that was the end of that. But I felt very sorry for him, because he is a true auteur. One of the great New Wave directors, and they didn’t respect his wishes, and I was all for him. It really was the highlight of my career to work with Godard. He was my hero.

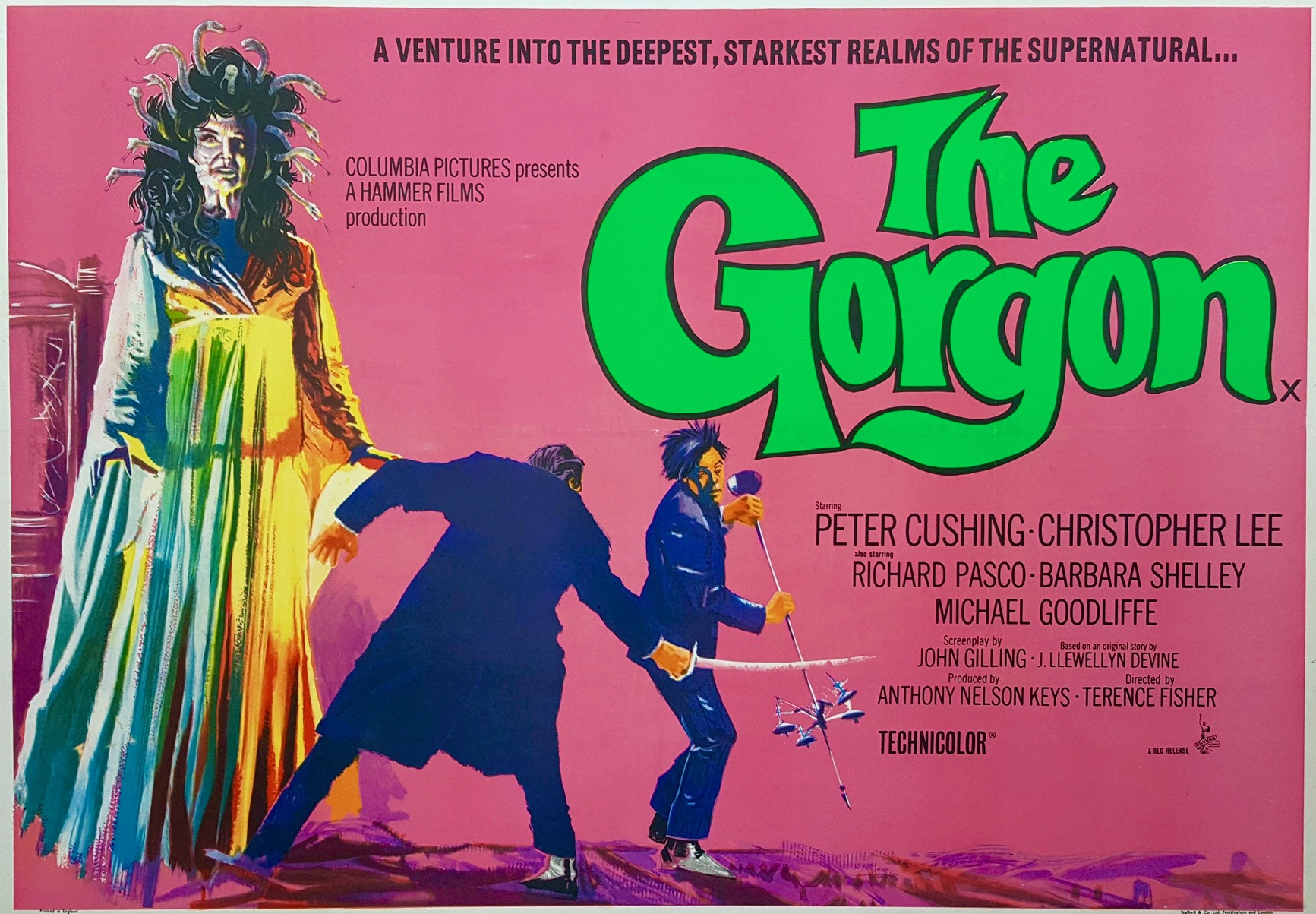

JT: Maybe we can move now to some of the horror movies you worked on, in the spirit of Halloween. I want to ask you about Candyman (1992), and Tales from the Hood (1995), but first I’d like to go back to 1964.

You basically started your career at Hammer working on The Evil of Frankenstein and The Gorgon in 1964. Here, for example, is a clip from The Gorgon, which gives us a sense of the Hammer style:

TR: Fantastic!

They’re beautifully photographed, these movies.

JT: In what respect?

TR: It’s a different sort of lighting now. Most movies are now shot with soft light, but these were all done with hard light, where you can really control the contrast much easier. What was also wonderful about working for Hammer at Bray Studios is that it was family-run in a great little studio with two stages, just outside London, on the Thames River. They had a wonderful restaurant with home-cooked meals.

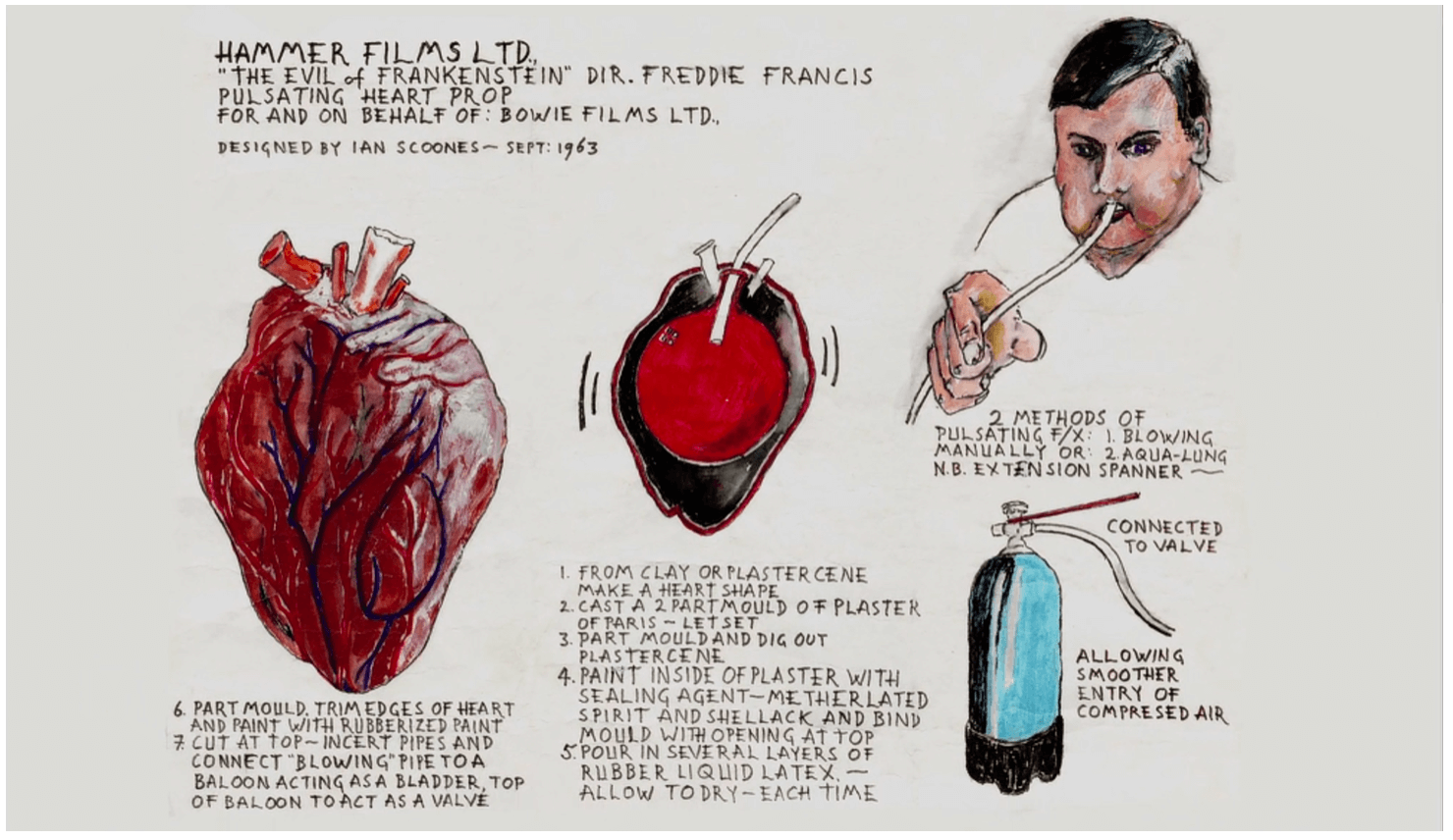

JT: Hammer had struck a deal with Universal to get the monster movies. They made six Frankenstein movies, five of which were directed by Terence Fisher, one of which was directed by Freddie Francis. The Evil of Frankenstein was directed by Freddie Francis. It’s a mad-scientist movie. Here’s a 30-second clip of the laboratory, which gives us our first glimpse:

JT: In what respect?

TR: It’s a different sort of lighting now. Most movies are now shot with soft light, but these were all done with hard light, where you can really control the contrast much easier. What was also wonderful about working for Hammer at Bray Studios is that it was family-run in a great little studio with two stages, just outside London, on the Thames River. They had a wonderful restaurant with home-cooked meals.

JT: Hammer had struck a deal with Universal to get the monster movies. They made six Frankenstein movies, five of which were directed by Terence Fisher, one of which was directed by Freddie Francis. The Evil of Frankenstein was directed by Freddie Francis. It’s a mad-scientist movie. Here’s a 30-second clip of the laboratory, which gives us our first glimpse:

TR: All the Hammer horrors had great production design. Who was this photographed by, John Wilcox?

JT: Yeah. Prior to this, Hammer had made two Frankenstein movies — The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957, followed by a direct sequel, The Revenge of Frankenstein in 1958. This one’s like a reboot in that they went back and retold the Frankenstein story from the beginning. But it’s directed by Freddie Francis, who was a very good cinematographer. Four years before directing this movie he won the Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Cinematography for his work on Sons and Lovers (1960), an adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s book that was directed by Jack Cardiff, another amazing cinematographer. What were you doing at Hammer?

TR: Clapper Boy, which is now called a Second Assistant Camera.

JT: What were the responsibilities?

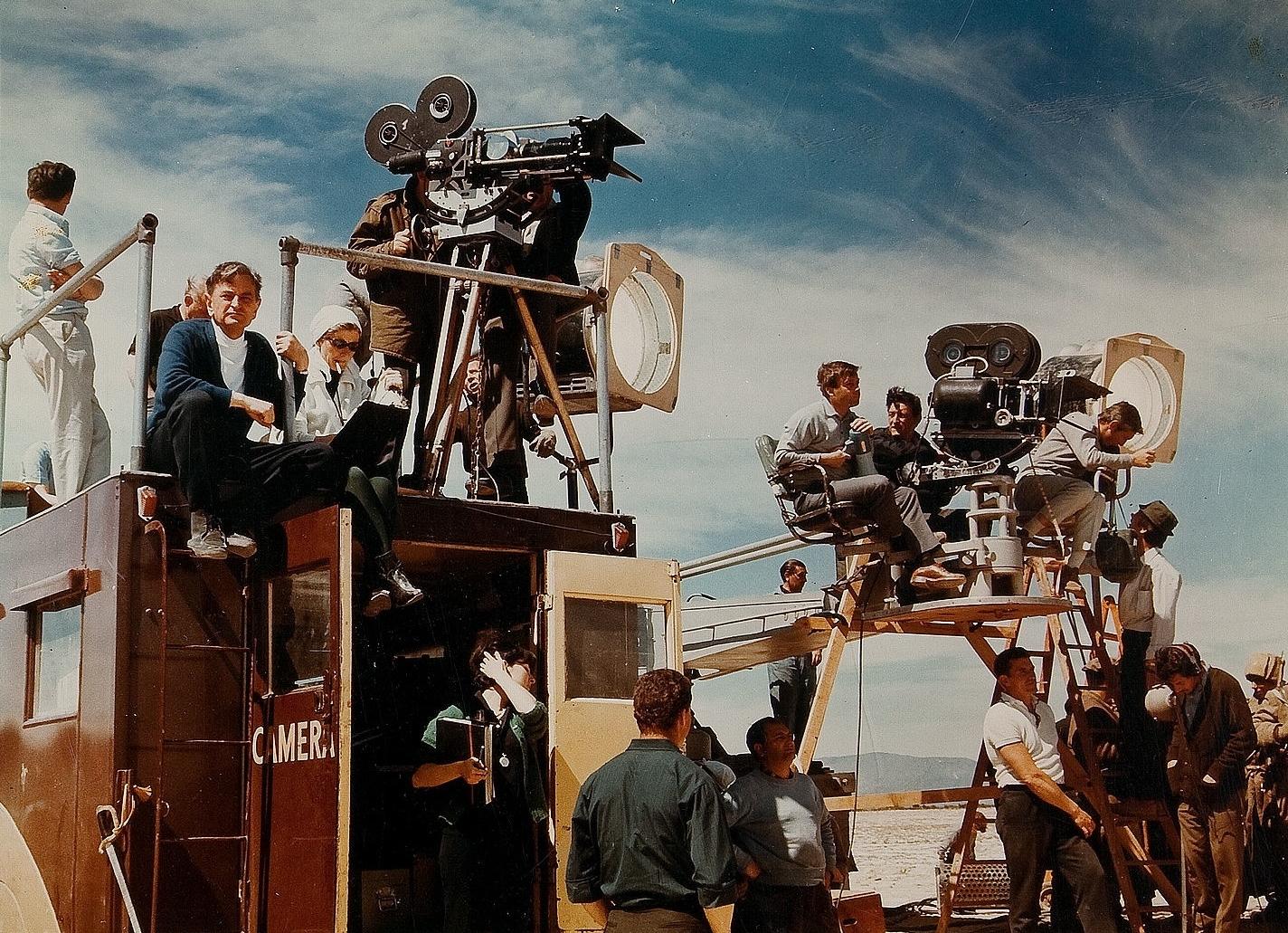

TR: You would help the focus puller, and you would load the magazines, and you would put the sticks in the clapper board. It was a four-man crew. There was the DP, camera operator, focus puller, and a clapper boy. But it was so much easier then because we didn’t work at the pace that they work at now. I got taken under the wing by John Wilcox, who was going to do a very big movie in Israel called Judith, with Peter Finch and Sophia Loren. He said “I’d like to take you with me,” so we went out to Israel and we were there for about seven months. It ended up being a terrible movie, but it was a wonderful experience, and as I say, you could ask questions if someone took you under their wing. It was there that I met Nicolas Roeg.

Nic Roeg was the Director-Cinematographer on the Second Unit and he had this crazy crew with him. They were just hilarious. So I used to hang out with those guys. And then toward the end of that movie he said he was leaving. He said I’m going to take you on my next film, as clapper boy, but I can’t tell you what it is. And then our movie was over and I got back to London and then there’s an urgent call for me to rush to MGM studios, so I went to MGM studios and in those days every studio had a camera department — permanent operators, permanent focus pullers, permanent clapper boys, you know — and they were very upset with me because they said I was going to go to Spain to work on Doctor Zhivago, and they couldn’t understand why they couldn’t use one of their own people.

JT: Freddie Young was at MGM at the time

TR: Yes, but he wasn’t shooting Doctor Zhivago. Nic Roeg was shooting Doctor Zhivago. I said “How long will I be away for?” and they said “Probably four months.” I was away for 52 weeks on that film.

Nic got fired after a month. What was incredible is that, in those days, if you worked for a DP you were part of a team, and I was Nic’s clapper boy. When Nic got fired I was going to leave with him, but he said “No, I want you to stay. It will be good for your career.” So I stayed, and I really hated David Lean because he fired Nic Roeg, you know? Someone told him that, and David Lean went out of his way to take me under his wing. I used to sit on the floor by his chair, and he’d talk to me, you know. In the end I liked him and I probably learned more about filmmaking from him than anybody else in the world. He was the consummate filmmaker. Everything had to be done to perfection. Every single thing. Every single frame. If you were panning around the room and you’re supposed to cut on the edge of a doorframe and the operator missed it by two inches, three inches, you’d go again. He was just meticulous about everything. He was wonderful with actors, and a tough director. But you can’t fault his work. Doctor Zhivago is an amazing movie.

JT: Yeah. Prior to this, Hammer had made two Frankenstein movies — The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957, followed by a direct sequel, The Revenge of Frankenstein in 1958. This one’s like a reboot in that they went back and retold the Frankenstein story from the beginning. But it’s directed by Freddie Francis, who was a very good cinematographer. Four years before directing this movie he won the Academy Award for Best Black-and-White Cinematography for his work on Sons and Lovers (1960), an adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s book that was directed by Jack Cardiff, another amazing cinematographer. What were you doing at Hammer?

TR: Clapper Boy, which is now called a Second Assistant Camera.

JT: What were the responsibilities?

TR: You would help the focus puller, and you would load the magazines, and you would put the sticks in the clapper board. It was a four-man crew. There was the DP, camera operator, focus puller, and a clapper boy. But it was so much easier then because we didn’t work at the pace that they work at now. I got taken under the wing by John Wilcox, who was going to do a very big movie in Israel called Judith, with Peter Finch and Sophia Loren. He said “I’d like to take you with me,” so we went out to Israel and we were there for about seven months. It ended up being a terrible movie, but it was a wonderful experience, and as I say, you could ask questions if someone took you under their wing. It was there that I met Nicolas Roeg.

Nic Roeg was the Director-Cinematographer on the Second Unit and he had this crazy crew with him. They were just hilarious. So I used to hang out with those guys. And then toward the end of that movie he said he was leaving. He said I’m going to take you on my next film, as clapper boy, but I can’t tell you what it is. And then our movie was over and I got back to London and then there’s an urgent call for me to rush to MGM studios, so I went to MGM studios and in those days every studio had a camera department — permanent operators, permanent focus pullers, permanent clapper boys, you know — and they were very upset with me because they said I was going to go to Spain to work on Doctor Zhivago, and they couldn’t understand why they couldn’t use one of their own people.

JT: Freddie Young was at MGM at the time

TR: Yes, but he wasn’t shooting Doctor Zhivago. Nic Roeg was shooting Doctor Zhivago. I said “How long will I be away for?” and they said “Probably four months.” I was away for 52 weeks on that film.

Nic got fired after a month. What was incredible is that, in those days, if you worked for a DP you were part of a team, and I was Nic’s clapper boy. When Nic got fired I was going to leave with him, but he said “No, I want you to stay. It will be good for your career.” So I stayed, and I really hated David Lean because he fired Nic Roeg, you know? Someone told him that, and David Lean went out of his way to take me under his wing. I used to sit on the floor by his chair, and he’d talk to me, you know. In the end I liked him and I probably learned more about filmmaking from him than anybody else in the world. He was the consummate filmmaker. Everything had to be done to perfection. Every single thing. Every single frame. If you were panning around the room and you’re supposed to cut on the edge of a doorframe and the operator missed it by two inches, three inches, you’d go again. He was just meticulous about everything. He was wonderful with actors, and a tough director. But you can’t fault his work. Doctor Zhivago is an amazing movie.

JT: So you’re 22 years old and getting lessons from David Lean. How about Freddie Young? He was a very distinguished cinematographer.

TR: I was very worried about Freddie Young, because he was a tough taskmaster, and I had never worked with him before. So the rest of the camera crew made me go to the airport to pick him up in the car, and when Freddie came out, I had a sign, and he came up to me — I had long hair, and nobody had long hair in those days — and he pulled my hair and said “We’re gonna get that cut, son.”

JT: I saw a documentary about Freddie Young and it sounded like he had a military edge to his crew.

TR: He did. In those days you had to fill out huge, huge camera reports to give notes to the nighttime grader. And I was filling out these reports, and I was in a hurry, because I got a date, and I sensed this breathing over my shoulder. It was Freddie Young and he said, “What’s that shit?” And I said, “This is your camera report, sir.” He couldn’t read my spider scrawl and so he picked me up and threw me against the wall, and he said, “You’re an idiot, a real idiot. I doubt you’ll ever become a DP. But if you do, I’ll give you a piece of advice. The story is in the eyes.”

JT: The eyes.

TR: All the emotion is in the eyes. And years later, years later, when I was a DP and had shot a lot of movies, the BSC, which I was a member of, had this Ladies Night. It was a big dinner and dance. And they always had a male guest of honor, for the ladies, and it was going to be Donald Sutherland. And Donald had to pull out at the last minute, so they called me, because I was in town with my then-wife, Jaclyn Smith, and was a pretty big star in those days, at that time — she was on Charlie’s Angels — and they said, “Would she be the guest of honor?” So I said “Yes, of course, we’ll just about make the dinner — because she’s working.” But we did, we got to the Strand Hotel, and we’re going up the stairs and the last dregs of people were going into the dinner, and there was a guy sitting on a sofa at the end of this room. He got up, and it’s Freddie Young, and he came running toward us, and he grabbed hold of Jaclyn and he said, “I told him to put the spark in the leading lady’s eye, but I didn’t mean him to take it this far.” He had a great sense of humor, Freddie.

TR: I was very worried about Freddie Young, because he was a tough taskmaster, and I had never worked with him before. So the rest of the camera crew made me go to the airport to pick him up in the car, and when Freddie came out, I had a sign, and he came up to me — I had long hair, and nobody had long hair in those days — and he pulled my hair and said “We’re gonna get that cut, son.”

JT: I saw a documentary about Freddie Young and it sounded like he had a military edge to his crew.

TR: He did. In those days you had to fill out huge, huge camera reports to give notes to the nighttime grader. And I was filling out these reports, and I was in a hurry, because I got a date, and I sensed this breathing over my shoulder. It was Freddie Young and he said, “What’s that shit?” And I said, “This is your camera report, sir.” He couldn’t read my spider scrawl and so he picked me up and threw me against the wall, and he said, “You’re an idiot, a real idiot. I doubt you’ll ever become a DP. But if you do, I’ll give you a piece of advice. The story is in the eyes.”

JT: The eyes.

TR: All the emotion is in the eyes. And years later, years later, when I was a DP and had shot a lot of movies, the BSC, which I was a member of, had this Ladies Night. It was a big dinner and dance. And they always had a male guest of honor, for the ladies, and it was going to be Donald Sutherland. And Donald had to pull out at the last minute, so they called me, because I was in town with my then-wife, Jaclyn Smith, and was a pretty big star in those days, at that time — she was on Charlie’s Angels — and they said, “Would she be the guest of honor?” So I said “Yes, of course, we’ll just about make the dinner — because she’s working.” But we did, we got to the Strand Hotel, and we’re going up the stairs and the last dregs of people were going into the dinner, and there was a guy sitting on a sofa at the end of this room. He got up, and it’s Freddie Young, and he came running toward us, and he grabbed hold of Jaclyn and he said, “I told him to put the spark in the leading lady’s eye, but I didn’t mean him to take it this far.” He had a great sense of humor, Freddie.

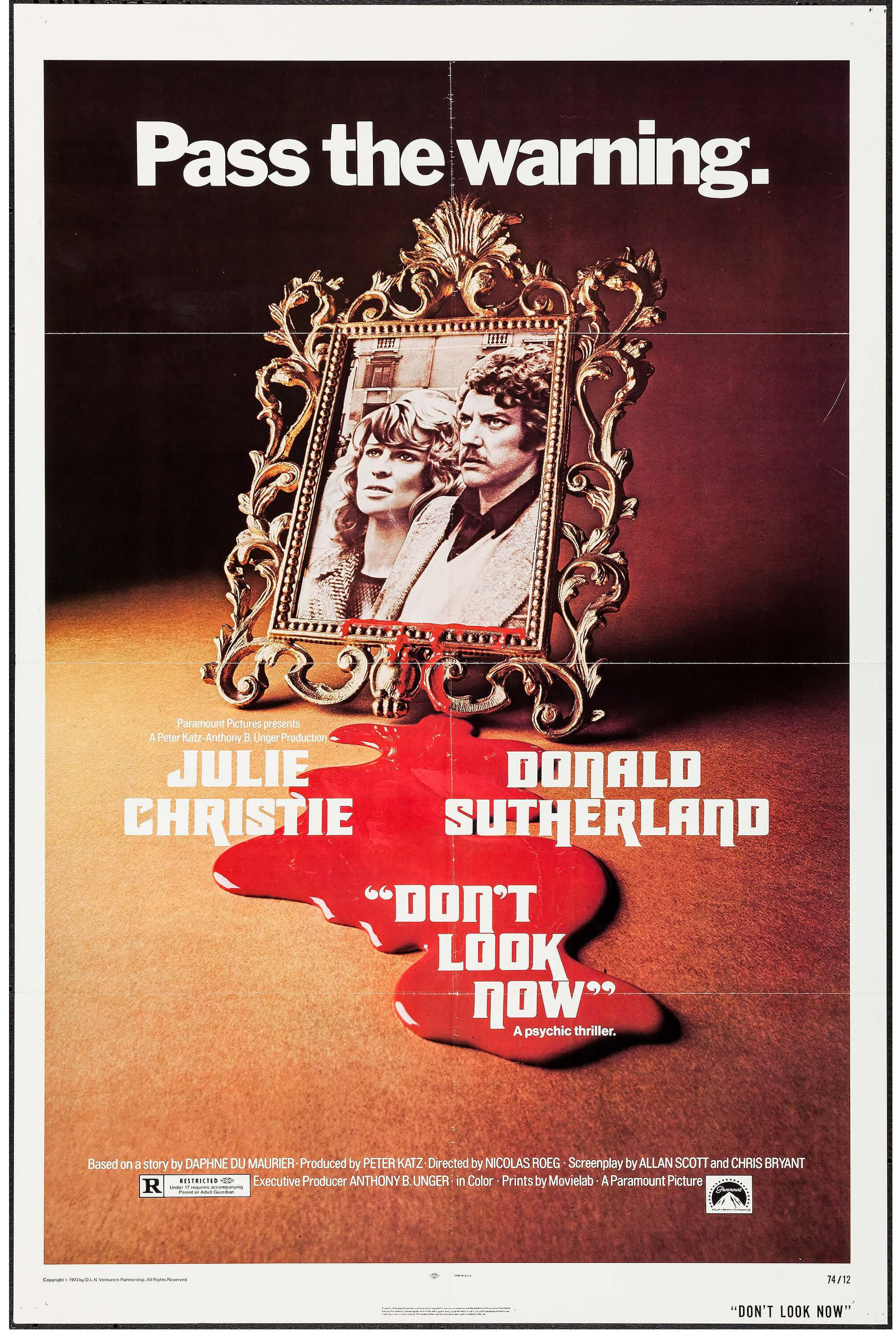

JT: Don’t Look Now (1973) was a very important movie for you.

TR: It was a great honor when Nic asked me to shoot Don’t Look Now. He had been a cinematographer himself. We were friends as much as anything. When I started with him he was like a father figure, then we were like older and younger brothers, and then we were just friends. All the movies I did with Nic were done on location. So we lived together, and that meant that every night we would have dinner together. We were both in our drinking days and we just keep talking about the movie, talking about the movie, talking about the movie. So I had a great understanding. But Nic would change directions. We may start off in the morning, block the actors, we’re ready to go, and something comes up and he changes his mind and goes in the opposite direction. He’s very open to all of that stuff.

TR: It was a great honor when Nic asked me to shoot Don’t Look Now. He had been a cinematographer himself. We were friends as much as anything. When I started with him he was like a father figure, then we were like older and younger brothers, and then we were just friends. All the movies I did with Nic were done on location. So we lived together, and that meant that every night we would have dinner together. We were both in our drinking days and we just keep talking about the movie, talking about the movie, talking about the movie. So I had a great understanding. But Nic would change directions. We may start off in the morning, block the actors, we’re ready to go, and something comes up and he changes his mind and goes in the opposite direction. He’s very open to all of that stuff.

JT: Do you remember any particular lessons you learned from him?

TR: The only piece of advice he gave me, when we were working on Don’t Look Now, was “Don’t be afraid of the dark.” I realized when we got to Venice, since we shot that in February, and Venice was a cold dark depressing city in the winter. It was horrible. And when it came to night shooting I knew what he meant. We couldn’t get Condors and you could only get lights up wherever you could get them, not where you wanted them, and a lot of it was just dark.

TR: The only piece of advice he gave me, when we were working on Don’t Look Now, was “Don’t be afraid of the dark.” I realized when we got to Venice, since we shot that in February, and Venice was a cold dark depressing city in the winter. It was horrible. And when it came to night shooting I knew what he meant. We couldn’t get Condors and you could only get lights up wherever you could get them, not where you wanted them, and a lot of it was just dark.

JT: How do you feel the cinematography contributed to whatever type of horror that film invokes?

TR: In America it’s called psychological horror, but it’s not really a horror film.

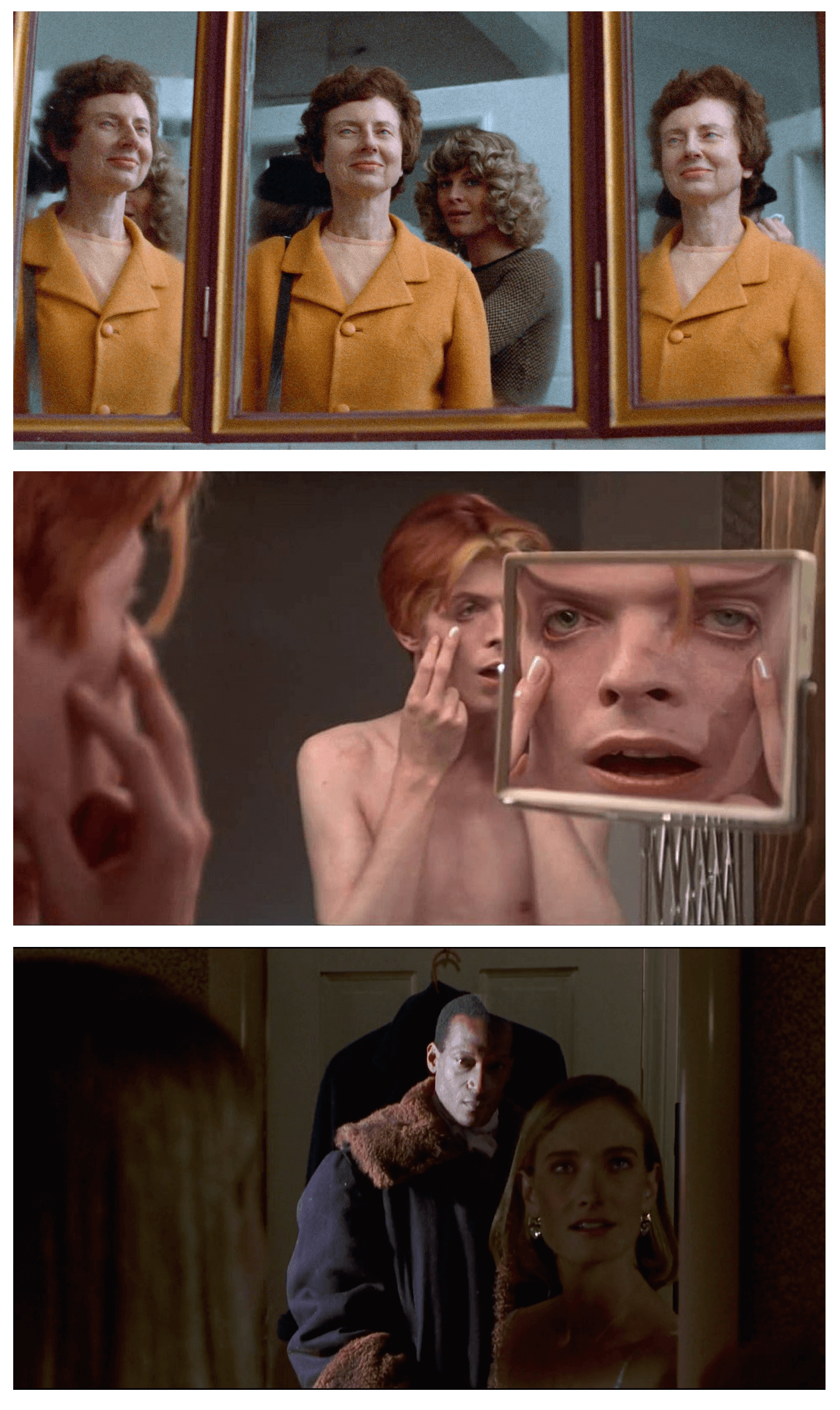

JT: There’s a shot I wanted to ask about — it’s a mirror scene, towards the beginning, with Julie Christie and two older women, one of whom was blind.

TR: In America it’s called psychological horror, but it’s not really a horror film.

JT: There’s a shot I wanted to ask about — it’s a mirror scene, towards the beginning, with Julie Christie and two older women, one of whom was blind.

TR: Did you see that mirror moving? What happened was I had all those on bevels. We put those mirrors up and they were all wired. I was laying across the top of the stalls with these wires, pulling the mirrors a little bit every time the camera moves, so you never see the camera.

JT: Like a puppeteer. Just one camera on this?

TR: Yes, the only time we used more than one camera was on the canal. You can’t use two cameras. And Nic Roeg always loved the zoom.

JT: You get a sense of that from the opening sequence of the film, which has such incredible images.

TR: We struck so lucky there, because we had that beautiful, cold, low, wintery sun. It’s beautiful, that light. We had it all four days. Don’t Look Now was a great movie, and I won a big award for that. I won the BAFTA Award. And what is weird, and it’s an arrogant thing to say, all the movies I was up against at the BAFTA — Sidney Samuelson who was the head of BAFTA at the time called me afterwards and said, “I shouldn’t tell you this, but you received more votes than anyone has ever received for cinematography.”

JT: Amazing.

TR: Working with Nic was always exciting because the other thing is that he had the most incredible sense of humor. When something would go wrong on set, and things invariably go wrong, he would always find some form of humor in it rather than pointing the finger at other crew members.

JT: That’s a good lesson, too. Do you like making mirror shots?

TR: I love mirrors, love mirrors. I did one shooting The Greek Tycoon for J. Lee Thompson, which we shot mostly in Greece and London. We also had some stuff to do in New York. But we shot a night club scene at Regine’s in New York. And in the dance floor area it was all mirrors. In those days I had to have a standby American DP because of the unions. I had this real idiot, and we were shooting in Regine’s and when we were scouting he said, “How are you going to do this with all the mirrors, kid?” He was a much older man and I was very young. All I did is sent out and got mirror tiles and then just stuck those to the original mirrors at a slightly different angle so we never saw ourselves. There’s a way around everything, you know. There’s a way around everything. There were no visual effects in those days…

JT: Did you feel like the mirror shots were particularly important in Candyman?

TR: Absolutely. Especially when I did that visual effect myself, where Candyman appears as she is looking in the mirror.

JT: Like a puppeteer. Just one camera on this?

TR: Yes, the only time we used more than one camera was on the canal. You can’t use two cameras. And Nic Roeg always loved the zoom.

JT: You get a sense of that from the opening sequence of the film, which has such incredible images.

TR: We struck so lucky there, because we had that beautiful, cold, low, wintery sun. It’s beautiful, that light. We had it all four days. Don’t Look Now was a great movie, and I won a big award for that. I won the BAFTA Award. And what is weird, and it’s an arrogant thing to say, all the movies I was up against at the BAFTA — Sidney Samuelson who was the head of BAFTA at the time called me afterwards and said, “I shouldn’t tell you this, but you received more votes than anyone has ever received for cinematography.”

JT: Amazing.

TR: Working with Nic was always exciting because the other thing is that he had the most incredible sense of humor. When something would go wrong on set, and things invariably go wrong, he would always find some form of humor in it rather than pointing the finger at other crew members.

JT: That’s a good lesson, too. Do you like making mirror shots?

TR: I love mirrors, love mirrors. I did one shooting The Greek Tycoon for J. Lee Thompson, which we shot mostly in Greece and London. We also had some stuff to do in New York. But we shot a night club scene at Regine’s in New York. And in the dance floor area it was all mirrors. In those days I had to have a standby American DP because of the unions. I had this real idiot, and we were shooting in Regine’s and when we were scouting he said, “How are you going to do this with all the mirrors, kid?” He was a much older man and I was very young. All I did is sent out and got mirror tiles and then just stuck those to the original mirrors at a slightly different angle so we never saw ourselves. There’s a way around everything, you know. There’s a way around everything. There were no visual effects in those days…

JT: Did you feel like the mirror shots were particularly important in Candyman?

TR: Absolutely. Especially when I did that visual effect myself, where Candyman appears as she is looking in the mirror.

TR: It’s a normal mirror but I’m using a two-way beam splitter. It’s a piece of glass that you put in front of the camera at an angle, and you light it. The light on him is on a dimmer, so you don’t see him, and then you bring the dimmer up and he appears there. It’s an in-camera effect.

JT: Candyman is described as an urban legend.

TR: Urban legends are great.

JT: Are there other examples?

TR: There’s an urban legend about a scuba diver that had been picked up out of the water somewhere by one of those scooper planes, the planes they use to gather water for fires. A scuba diver got caught in one of those and when they dropped the water he was found in the woods.

JT: A scuba diver in the woods.

TR: That’s another urban legend.

JT: Candyman is described as an urban legend.

TR: Urban legends are great.

JT: Are there other examples?

TR: There’s an urban legend about a scuba diver that had been picked up out of the water somewhere by one of those scooper planes, the planes they use to gather water for fires. A scuba diver got caught in one of those and when they dropped the water he was found in the woods.

JT: A scuba diver in the woods.

TR: That’s another urban legend.

JT: Candyman has a mesmerizing title sequence. It’s the combination of Philip Glass’s music, which is haunting and gothic but also hypnotic in its repetitive sounds, and then at the same time there’s the super-steady helicopter shot that looks straight down at the freeway and flies over it, following a straight line in one direction. It introduces camera movement as an active presence in the film.

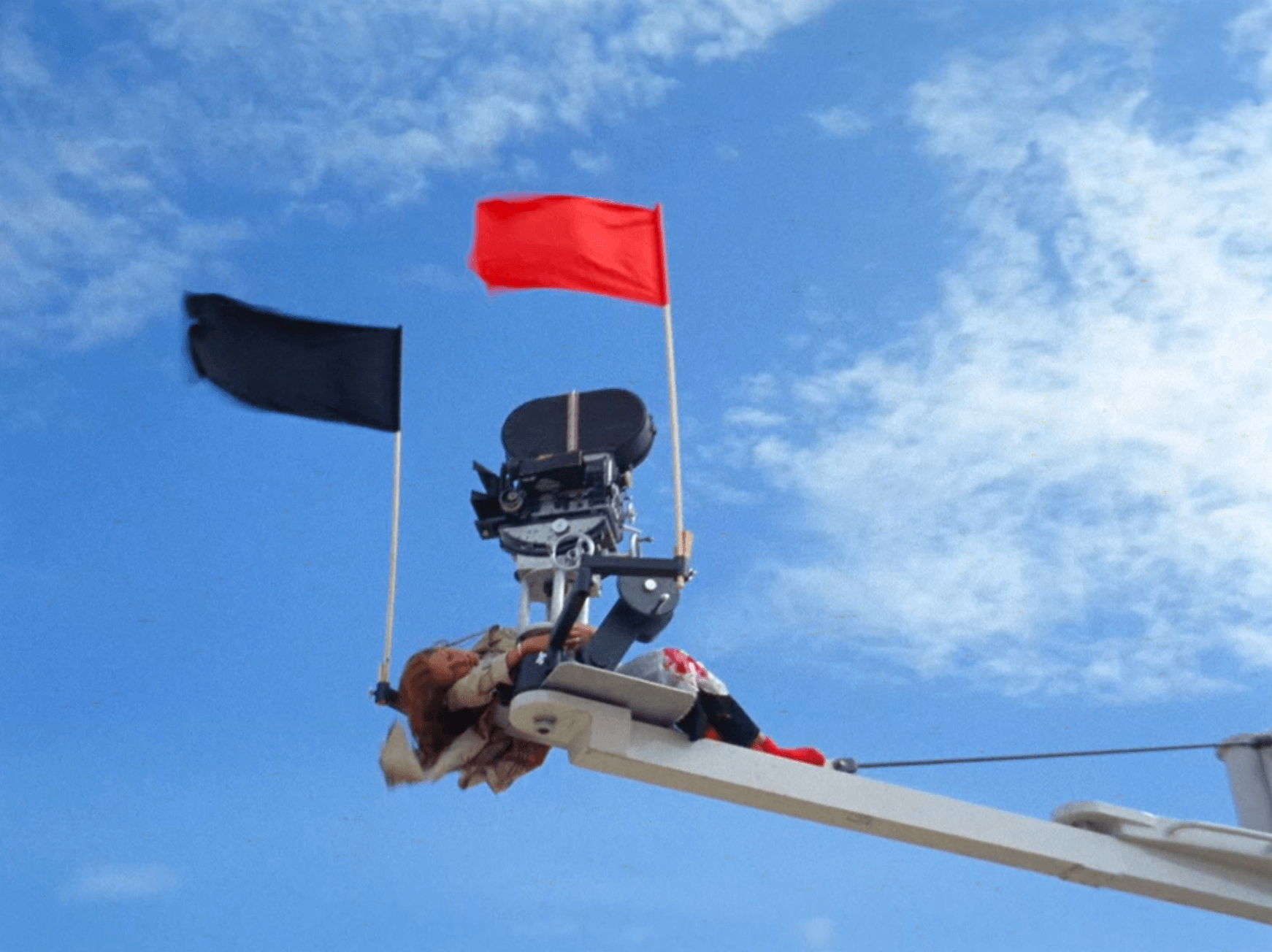

TR: We had a lot of camera movement. I like the camera to move. The opening shot is done from a helicopter. I didn’t get in the helicopter because the camera was on a stabilized head in this helicopter pointing straight down. If it had been a typical helicopter shot I would have done that myself hanging out the side on a Tyler Mount. I used to like to do that, but I wouldn’t like to do it anymore, because it’s dangerous. But I used to like to do that. I did it all the way through The Greek Tycoon. But this — the opening of Candyman — is perfectly stabilized, so it’s beautiful. It was a big dome hanging underneath the helicopter.

JT: I read that Virginia Madsen was hypnotized before filming certain scenes?

TR: Ah. Well that was Bernard Rose. I mean I love Bernard Rose, he was crazy as a loon, but I love Bernard Rose. He was a very good director. I remember once when we were in the garage, and Candyman appears. He said we’re going to hypnotize her now. So he started doing this thing [a waving hand makes the gesture of a pendulum]. And then suddenly, we’re ready to shoot, and I just whispered, “Virginia, move to your left a little bit.” So she wasn’t hypnotized. He went fucking crazy. She wasn’t hypnotized. But it was just wonderful.

JT: In terms of the camerawork there’s a motif in the film of a crane shot that swoops down and curves back up outside of Helen’s apartment.

TR: That was a Chapman Titan. It’s a huge crane, a rideable crane, and I’ll never forget that because we were at Cabrini-Green and they wouldn’t let us shoot at night there, we had to do it at dusk. I had a big arc light on top of the crane, and it was so cold. It was just before Christmas and I had this huge red snow goose on, you know, and there was a policeman down there and he said, “Are you going to wear that jacket?” And I said yeah, and he said, “Well I wouldn’t if I was you.” Well anyway we started to shoot and there were all these people coming out and all of a sudden there was a BANG BANG BANG, and they shot out the generator. The generator driver just got up and ran. It was very violent in those days. So I quickly came down off that crane.

JT: And a lot of the film was shot in-studio here?

TR: Yeah we shot at a great studio, Robert Aldrich Studios in Silverlake.

JT: Robert Aldrich, as in Kiss Me Deadly?

TR: Yeah, he had his own studio, with two stages. It was great. I think they’re still there, though they may be called something else now. They were wonderful studios. So we built all the sets. The sets were great. And I always loved, one of my favorite sets, was Candyman’s lair. When she goes through the hole in the wall and up the stairs into Candyman’s lair. That was an amazing set. The Art Director built it right to the ceiling. I said, “You have to cut 3 feet off this, because I have to light it. We’ll be using a crane in there.” So we went back and forth and back and forth and she refused to cut it off, the Production Designer. And I said you’ve got to. So I went to the producers and said, “You’ve got to tell her to cut this off.” Because I had to be able to light it from the top, and just put an overall feel of moonlight. I thought that was a great set.

JT: So you wanted that interior space to feel moonlit?

TR: That’s right. We could have strong kickers coming through, but it had to be a dark, moody look. She was a great actress, Virginia Madsen. She was perfect for that movie.

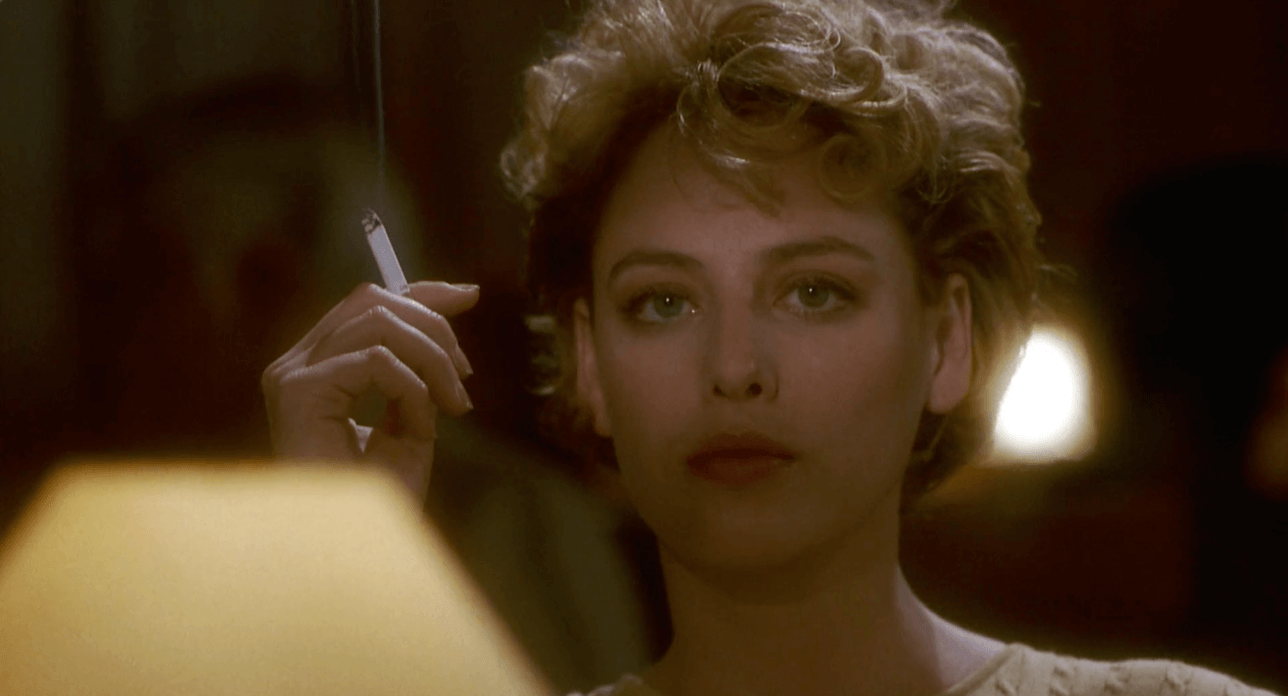

JT: There’s something very striking about the way she’s lit. For instance in the dinner scene with the arrogant professor who tells the story Candyman’s death. It’s a gruesome story of racist violence and yet Virginia Madsen’s character is entranced. At first she’s lit one way, and then, cut, we see her again in another, special kind of lighting. It reminds me of Dracula.

TR: We had a lot of camera movement. I like the camera to move. The opening shot is done from a helicopter. I didn’t get in the helicopter because the camera was on a stabilized head in this helicopter pointing straight down. If it had been a typical helicopter shot I would have done that myself hanging out the side on a Tyler Mount. I used to like to do that, but I wouldn’t like to do it anymore, because it’s dangerous. But I used to like to do that. I did it all the way through The Greek Tycoon. But this — the opening of Candyman — is perfectly stabilized, so it’s beautiful. It was a big dome hanging underneath the helicopter.

JT: I read that Virginia Madsen was hypnotized before filming certain scenes?

TR: Ah. Well that was Bernard Rose. I mean I love Bernard Rose, he was crazy as a loon, but I love Bernard Rose. He was a very good director. I remember once when we were in the garage, and Candyman appears. He said we’re going to hypnotize her now. So he started doing this thing [a waving hand makes the gesture of a pendulum]. And then suddenly, we’re ready to shoot, and I just whispered, “Virginia, move to your left a little bit.” So she wasn’t hypnotized. He went fucking crazy. She wasn’t hypnotized. But it was just wonderful.

JT: In terms of the camerawork there’s a motif in the film of a crane shot that swoops down and curves back up outside of Helen’s apartment.

TR: That was a Chapman Titan. It’s a huge crane, a rideable crane, and I’ll never forget that because we were at Cabrini-Green and they wouldn’t let us shoot at night there, we had to do it at dusk. I had a big arc light on top of the crane, and it was so cold. It was just before Christmas and I had this huge red snow goose on, you know, and there was a policeman down there and he said, “Are you going to wear that jacket?” And I said yeah, and he said, “Well I wouldn’t if I was you.” Well anyway we started to shoot and there were all these people coming out and all of a sudden there was a BANG BANG BANG, and they shot out the generator. The generator driver just got up and ran. It was very violent in those days. So I quickly came down off that crane.

JT: And a lot of the film was shot in-studio here?

TR: Yeah we shot at a great studio, Robert Aldrich Studios in Silverlake.

JT: Robert Aldrich, as in Kiss Me Deadly?

TR: Yeah, he had his own studio, with two stages. It was great. I think they’re still there, though they may be called something else now. They were wonderful studios. So we built all the sets. The sets were great. And I always loved, one of my favorite sets, was Candyman’s lair. When she goes through the hole in the wall and up the stairs into Candyman’s lair. That was an amazing set. The Art Director built it right to the ceiling. I said, “You have to cut 3 feet off this, because I have to light it. We’ll be using a crane in there.” So we went back and forth and back and forth and she refused to cut it off, the Production Designer. And I said you’ve got to. So I went to the producers and said, “You’ve got to tell her to cut this off.” Because I had to be able to light it from the top, and just put an overall feel of moonlight. I thought that was a great set.

JT: So you wanted that interior space to feel moonlit?

TR: That’s right. We could have strong kickers coming through, but it had to be a dark, moody look. She was a great actress, Virginia Madsen. She was perfect for that movie.

JT: There’s something very striking about the way she’s lit. For instance in the dinner scene with the arrogant professor who tells the story Candyman’s death. It’s a gruesome story of racist violence and yet Virginia Madsen’s character is entranced. At first she’s lit one way, and then, cut, we see her again in another, special kind of lighting. It reminds me of Dracula.

TR: That’s right. In the eyes. That’s just a key coming straight in, and some nets to create shadow, a double on top and a single on the bottom. And I have a little bit of diffusion on it to soften it up, to go straight to her eyes. Because of the way it’s lit you’re looking at her eyes. That’s an old-fashioned trick. They don’t do that anymore because everyone uses soft light.

JT: It’s an important shot.

TR: It’s a very important shot. But also, the other thing is — all emotion is in the eyes, in acting. What’s strange is, you look at a lot of modern movies and you don’t see people’s eyes, you know? It’s all different now.

JT: So when you light a scene, how the eyes are lit is important to you.

TR: I think so — and close-ups — absolutely.

JT: Sometimes I hear of cinematographers who have a little light they keep by the camera to aim at the eyes, I think it’s called a kicker —

TR: No, a kicker is coming from the back. Kicker is very important to use on black skin tones. It can be hard to light black people if you have a scene with white and black skin tones together, because one is darker than the other, so you put kicker coming in from the side, with a lavender filter on it, that helps you a great deal.

JT: I wanted to ask about another sequence from Candyman, which is sort of a transition sequence but culminates in some really important shots that raise questions about the other, aerial shots we saw earlier in the film. I think this sequence showcases the role that lighting and camerawork play in the narration of the film.

JT: It’s an important shot.

TR: It’s a very important shot. But also, the other thing is — all emotion is in the eyes, in acting. What’s strange is, you look at a lot of modern movies and you don’t see people’s eyes, you know? It’s all different now.

JT: So when you light a scene, how the eyes are lit is important to you.

TR: I think so — and close-ups — absolutely.

JT: Sometimes I hear of cinematographers who have a little light they keep by the camera to aim at the eyes, I think it’s called a kicker —

TR: No, a kicker is coming from the back. Kicker is very important to use on black skin tones. It can be hard to light black people if you have a scene with white and black skin tones together, because one is darker than the other, so you put kicker coming in from the side, with a lavender filter on it, that helps you a great deal.

JT: I wanted to ask about another sequence from Candyman, which is sort of a transition sequence but culminates in some really important shots that raise questions about the other, aerial shots we saw earlier in the film. I think this sequence showcases the role that lighting and camerawork play in the narration of the film.

TR: We did a lot of tracking shots in this movie.

JT: Here the camera goes through a mirror above a sink, and once you go through that portal you enter this other space, which resembles the open mouth of Candyman, which we saw in that other iconic moment of Helen walking through the mouth, but this blood-splattered space is someplace different.

TR: It’s hard to remember. When we went into this space with the candles, I was sitting on a dolly shooting handheld and they pushed me through the wall and I got off and continued walking, until she went up the stairs, and then we were in a crane in the lair. Handheld is very easy to do if you do it properly. You have to control your breathing. You really have to. There are three different kinds of movement. A crane is rock-steady because it has a stabilized head. A Steadicam has a slightly different feeling. It’s sort of floating. And handheld. And each of those three styles give you a different feeling. But with handheld you have to breathe as you walk.

JT: In the sequence where Helen is wheeled into the jail on a gurney it looks like she’s being wheeled into an operating room by doctors and nurses. The camera is in motion. When she arrives in a room, the camera elevates in a way that resembles the opening freeway shot. The camera is looking straight down.

TR: We’re on a crane there, to get us up there.

JT: And then suddenly we’re introduced to what would seem to be a POV shot! Maybe?

JT: Here the camera goes through a mirror above a sink, and once you go through that portal you enter this other space, which resembles the open mouth of Candyman, which we saw in that other iconic moment of Helen walking through the mouth, but this blood-splattered space is someplace different.

TR: It’s hard to remember. When we went into this space with the candles, I was sitting on a dolly shooting handheld and they pushed me through the wall and I got off and continued walking, until she went up the stairs, and then we were in a crane in the lair. Handheld is very easy to do if you do it properly. You have to control your breathing. You really have to. There are three different kinds of movement. A crane is rock-steady because it has a stabilized head. A Steadicam has a slightly different feeling. It’s sort of floating. And handheld. And each of those three styles give you a different feeling. But with handheld you have to breathe as you walk.

JT: In the sequence where Helen is wheeled into the jail on a gurney it looks like she’s being wheeled into an operating room by doctors and nurses. The camera is in motion. When she arrives in a room, the camera elevates in a way that resembles the opening freeway shot. The camera is looking straight down.

TR: We’re on a crane there, to get us up there.

JT: And then suddenly we’re introduced to what would seem to be a POV shot! Maybe?

TR: Right. You know, Bernard and I worked very well together. He had a very strong vision of how he wanted things to be. I mean that’s a cinematographer's job. A cinematographer’s main job is to put the director’s vision on the screen. A lot of directors have a hard time putting that into words, strangely enough. But Bernard could put it into words so I totally understood what he wanted it. And then you hope you can enhance that vision for him.

I want to just say something — if you’ve got great production design going for you, and great set decoration, and you’ve done your prep work, then the actual cinematography is pretty easy.

JT: What do you mean by prep work?