Billy Wilder

The Art of Little Ruses

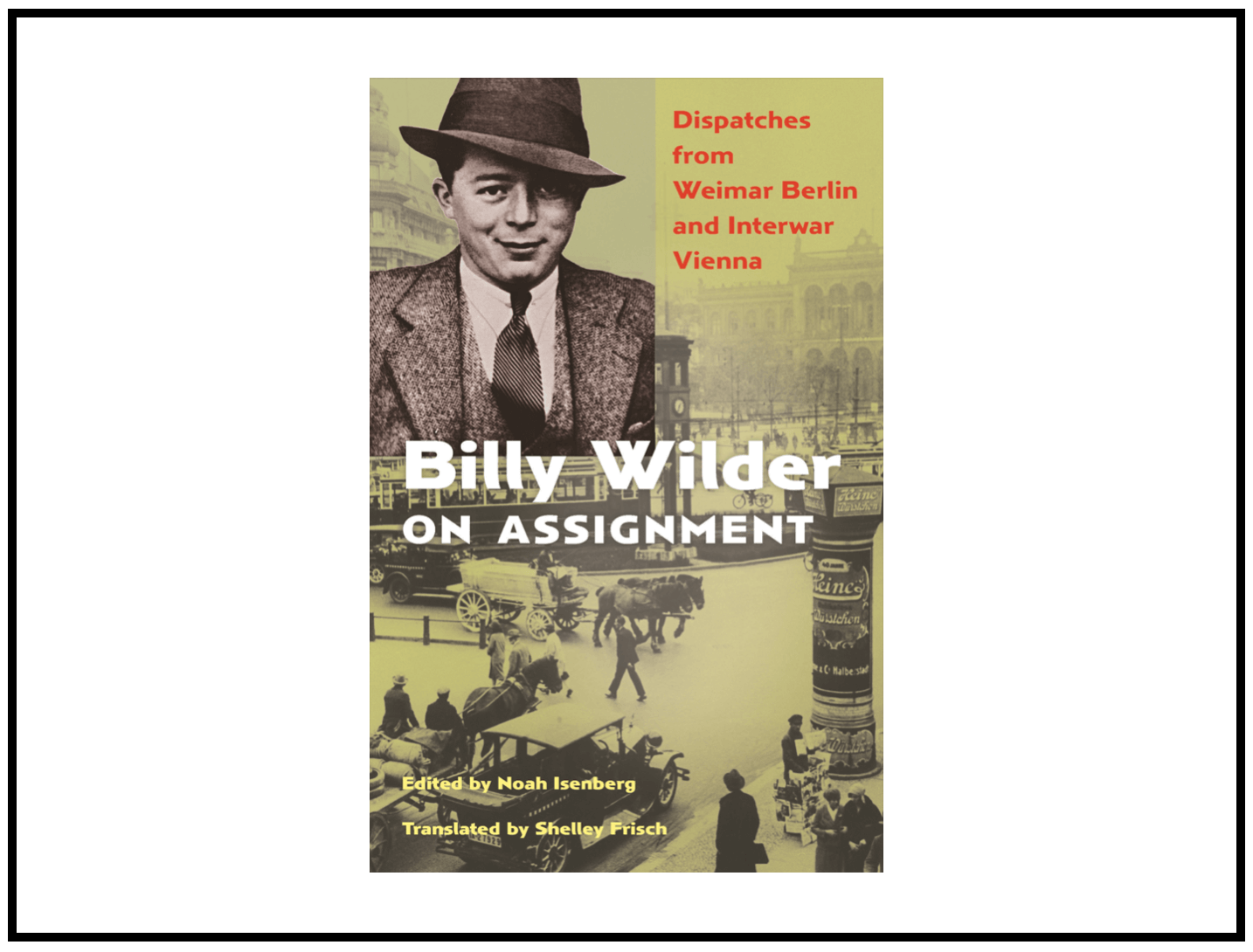

Billy Wilder was a verbal magician who wrote some of the most memorable lines in the history of movies. “The Art of Little Ruses” is a piece he published when he was still twenty years old. It was 1927 and Wilder was living in Berlin, working as a freelance reporter with a gift for gab who walked fast and cut his cigarettes in half to make them last longer. The frontispiece seen above is a 1926 caricature of Billie on the beat, a “racing reporter” about to relocate from Vienna. As translator Shelley Frisch notes, Wilder’s writing style in these years had a way of combining Berlin slang with Vienna slang and sustained a sly, roundabout humor that was neither belly laugh nor too subtle to notice but somewhere in between. The following text is an early gem included in Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna, edited and introduced by Noah Isenberg and published and reproduced here courtesy of Princeton University Press.

I don’t want to come right out and insist that, starting this very day, schools teach the art of lying, by which I mean using postures and facial expressions, gestures and inflections of the voice to convey the opposite of truth with sweeping powers of persuasion and achieve smashing success. I don’t mean to demand it explicitly in the framework of pushing the latest educational reform, for I, too, am ensnared in a curiously outdated set of ideas, and I appreciate and honor the so-called truth. But I can easily imagine that in two or three decades lies will be regarded as an indispensable and hence utterly unobjectionable implement in our daily lives, and their correct and appropriate use could be learned systematically by employing the scientific method.

The lie as mandatory school subject, accessible to everyone and anyone, a matter entailing assiduous effort and tireless aspiration, would no longer be the privilege of the few who have a natural predisposition in this arena: that, I think, would be the consummate moral and social justification of this hitherto maligned resource on a strictly democratic basis.

This would seem to provide a path for the art of modern education, which, for some mysterious reason, has always been overlooked. Hasn’t it ever occurred to you what an irresponsible waste of life, what a scholastic peculiarity it is, that in light of today’s challenges, the schools—even the most progressive ones—still fail to include a Practical Life Skills subject in the curriculum? That everyone who in their earliest childhood has already mastered the square root of two, Mariotte and Gay-Lussac’s law, and the years of Saint Gregory the Great’s papacy has to employ his own mental powers, in his fortieth year of life, to figure out what tools, dialectical methods, minor judgments, and ruses he needs to argue with his wife, or something of that sort, and it takes him countless attempts to get there?—You, young friend and author of an important sociological treatise, approach an influential patron. You enter his study, feeling sure of your significance, the lofty worth of your pursuit, the excellence of your achievement. But lo and behold! Your posturing is reduced to a low level of groveling, your rapid breathing robs your voice of the proper intonation and the requisite chest resonance. Your gestures are feeble and unconvincing. In short, you’re simply not in a position to present yourself, to breathe life credibly into your presentation, you’re fascinated and riveted by the superb sweeping motion with which your impressive destiny reaches for the needed mouthpiece, and in the ensuing pause, you lose your train of thought to analytical ideas about the nature of this greatness instead of keeping your own machinery in order. Nervousness? No, friend! Ignorance! Obliviousness! You simply ought to have learned it.—Where?— That’s the problem. . . .

Isn’t it really deeply shameful, even downright inexplicable, that in the era of scientific approaches to advertising, of experimental and psychological job testing, and all other Americanizing achievements in seamless life management, each individual is still forced to learn firsthand, over time, what could have been conveyed in a single year of systematic instruction in matters of tones of voice, catchphrases, arm movements, and facial gestures? And there he stands, bloated with life experience, as these ludicrous yet indispensable trifles are grandiosely labeled, with the sort of callousness of a boss who has no intention of sparing a trainee from any obstacles or the slightest failure. This approach to life is truly medieval, wallowing as it does in cumbersome dark insinuations, ominous prophesies, and pompous admonitions, instead of coming out and creating a school for things of this sort, teaching young people the art of swindling in an exciting and lively manner. What a gain in time! What a gain in vitality! And how simple the setup of this new discipline; all it would entail would be a study of physiognomy, human typology, plus a little instruction in conflicts, drama, and vocal exercises.—“Today we are coming to the subject of indignation” will—we hope—be what a teacher says in class in the not-too-distant future. “In the last class, we learned how to accept ingratiating praise, and we’re now moving on to indignation and the three practical forms it can take. Lederer, give us a short summary of what we’ve learned!”—And Lederer, in his seventeenth year of life, will step forward, and with the most magnificent ease, smoothly and unhesitatingly, present the eight or ten words and gestures that we, now forty years old, can barely stammer out without focusing every fiber of our being each time we have to do it. “Very good, Lederer,” the teacher will say, “just make your voice a little deeper. Make the movement of your hand toward the floor somewhat more pronounced, and slow down the whole thing by two seconds.” And one will progress to the three kinds of indignation, greeting techniques, disdainful posturing, and communicating with the authorities and eventually bring the final phase of the course to a successful conclusion with the difficult but vital topic of self-promotion.

Berliner Börsen Courier, May 1, 1927

Translated by Shelley Frisch

The lie as mandatory school subject, accessible to everyone and anyone, a matter entailing assiduous effort and tireless aspiration, would no longer be the privilege of the few who have a natural predisposition in this arena: that, I think, would be the consummate moral and social justification of this hitherto maligned resource on a strictly democratic basis.

This would seem to provide a path for the art of modern education, which, for some mysterious reason, has always been overlooked. Hasn’t it ever occurred to you what an irresponsible waste of life, what a scholastic peculiarity it is, that in light of today’s challenges, the schools—even the most progressive ones—still fail to include a Practical Life Skills subject in the curriculum? That everyone who in their earliest childhood has already mastered the square root of two, Mariotte and Gay-Lussac’s law, and the years of Saint Gregory the Great’s papacy has to employ his own mental powers, in his fortieth year of life, to figure out what tools, dialectical methods, minor judgments, and ruses he needs to argue with his wife, or something of that sort, and it takes him countless attempts to get there?—You, young friend and author of an important sociological treatise, approach an influential patron. You enter his study, feeling sure of your significance, the lofty worth of your pursuit, the excellence of your achievement. But lo and behold! Your posturing is reduced to a low level of groveling, your rapid breathing robs your voice of the proper intonation and the requisite chest resonance. Your gestures are feeble and unconvincing. In short, you’re simply not in a position to present yourself, to breathe life credibly into your presentation, you’re fascinated and riveted by the superb sweeping motion with which your impressive destiny reaches for the needed mouthpiece, and in the ensuing pause, you lose your train of thought to analytical ideas about the nature of this greatness instead of keeping your own machinery in order. Nervousness? No, friend! Ignorance! Obliviousness! You simply ought to have learned it.—Where?— That’s the problem. . . .

Isn’t it really deeply shameful, even downright inexplicable, that in the era of scientific approaches to advertising, of experimental and psychological job testing, and all other Americanizing achievements in seamless life management, each individual is still forced to learn firsthand, over time, what could have been conveyed in a single year of systematic instruction in matters of tones of voice, catchphrases, arm movements, and facial gestures? And there he stands, bloated with life experience, as these ludicrous yet indispensable trifles are grandiosely labeled, with the sort of callousness of a boss who has no intention of sparing a trainee from any obstacles or the slightest failure. This approach to life is truly medieval, wallowing as it does in cumbersome dark insinuations, ominous prophesies, and pompous admonitions, instead of coming out and creating a school for things of this sort, teaching young people the art of swindling in an exciting and lively manner. What a gain in time! What a gain in vitality! And how simple the setup of this new discipline; all it would entail would be a study of physiognomy, human typology, plus a little instruction in conflicts, drama, and vocal exercises.—“Today we are coming to the subject of indignation” will—we hope—be what a teacher says in class in the not-too-distant future. “In the last class, we learned how to accept ingratiating praise, and we’re now moving on to indignation and the three practical forms it can take. Lederer, give us a short summary of what we’ve learned!”—And Lederer, in his seventeenth year of life, will step forward, and with the most magnificent ease, smoothly and unhesitatingly, present the eight or ten words and gestures that we, now forty years old, can barely stammer out without focusing every fiber of our being each time we have to do it. “Very good, Lederer,” the teacher will say, “just make your voice a little deeper. Make the movement of your hand toward the floor somewhat more pronounced, and slow down the whole thing by two seconds.” And one will progress to the three kinds of indignation, greeting techniques, disdainful posturing, and communicating with the authorities and eventually bring the final phase of the course to a successful conclusion with the difficult but vital topic of self-promotion.

Berliner Börsen Courier, May 1, 1927

Translated by Shelley Frisch

Billy Wilder in his office in 1980, speaking with Michel Ciment about his early journalism, fascism, and Freud.

From Portrait of a 60% Perfect Man (Annie Tresgot, 1982)

From Portrait of a 60% Perfect Man (Annie Tresgot, 1982)