Artist Rosa Barba on Expanding Cinema and Three Films to Pack for Outer Space

Rosa Barba, In a Perpetual Now, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

22.08.2021 - 16.01.2022

22.08.2021 - 16.01.2022

Rosa Barba, congratulations on your new exhibition, Drawing the Infinite, which opens April 06 at Luhring Augustine in Tribeca.

The video we can see above leads us through your exhibition In a Perpetual Now, which you recently presented at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The Neue Nationalgalerie was the last major building designed by the celebrated modernist architect Mies van der Rohe — it opened in 1968 and your exhibition inaugurated its 2021 reopening after a six-year renovation. Can you talk about how you designed this show? The installation has a unifying architectural structure called Blind Volumes, which is composed of several intersecting steel frames arranged to resemble one of Mies’s unrealized projects, the Brick Country House, conceived around 1924. How did you arrive at the idea for your Blind Volumes exhibition system, which has taken on different configurations over a series of exhibitions?

The video we can see above leads us through your exhibition In a Perpetual Now, which you recently presented at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The Neue Nationalgalerie was the last major building designed by the celebrated modernist architect Mies van der Rohe — it opened in 1968 and your exhibition inaugurated its 2021 reopening after a six-year renovation. Can you talk about how you designed this show? The installation has a unifying architectural structure called Blind Volumes, which is composed of several intersecting steel frames arranged to resemble one of Mies’s unrealized projects, the Brick Country House, conceived around 1924. How did you arrive at the idea for your Blind Volumes exhibition system, which has taken on different configurations over a series of exhibitions?

The Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, shortly after its opening in 1968.

Photo: ©Archiv Neue Nationalgalerie

Photo: ©Archiv Neue Nationalgalerie

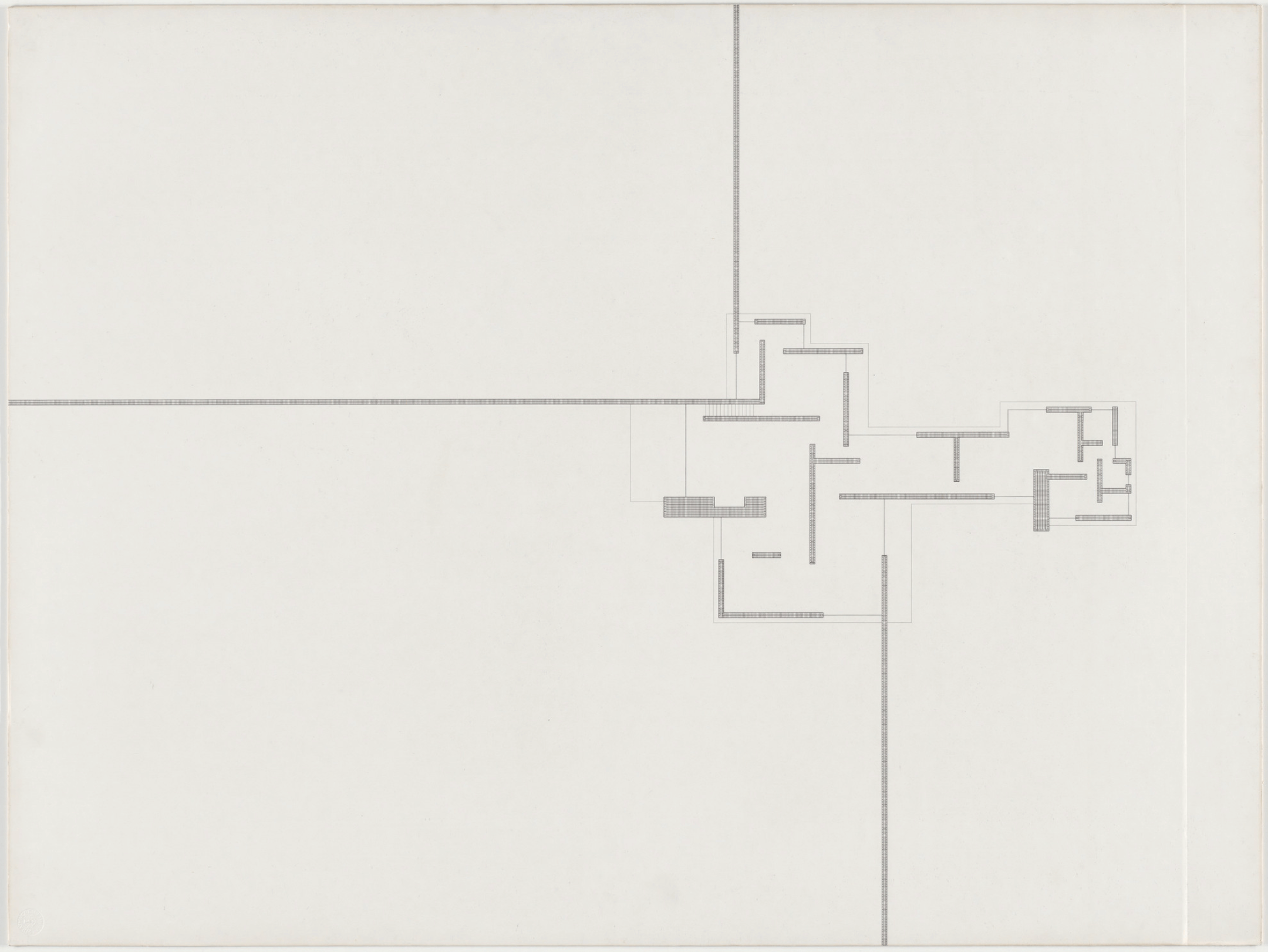

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Brick Country House, project, Potsdam-Neubabelsberg, Plan, 1924. ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Rosa Barba, In a Perpetual Now, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 22.08.2021 - 16.01.2022

Rosa Barba, In a Perpetual Now, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 22.08.2021 - 16.01.2022

Blind Volumes / Backstein (2021) is an installation made of steel, plexiglass, screens, and platforms, and takes van der Rohe’s 1924 drawing for an unrealized “Brick Country House” as a point of inspiration, accentuating the way in which his legacy is a framing device here. This work is also the physical structure of the exhibition itself as it draws space and defines space. From this “shelf system,” which also echoes with the history of exhibition displays, synchronized films and sculptures are placed in a sequenced choreography.

Architecture in this context is not merely three-dimensional space but a temporal process that constantly updates itself; it constructs itself in the movement and perception of subjects, and thus it itself remains mobile. Moreover, here architecture is meant to create spaces for unforeseen resonances between the designing subject and social communities (bodies in motion) and their living environment.

The title In a Perpetual Now is intriguing given your interest in abstraction, kinetics, and projectected light — concerns we might associate with avant-garde figures from the 1920s like László Moholy-Nagy and Walter Ruttmann, or with the expanded cinema experiments of the 1960s and 70s. In other words, your exhibition conveys a historical consciousness, so I'm wondering what you mean by In a Perpetual Now in this context?

Time is a recurring protagonist and tool in my work to examine or try to understand the world around us. I often use cinema to move between times, in order to stage an intervention in a real space, confronting the division between public and private, fantasy and reality. This allows me to navigate the past and merge it with present and future desires or preoccupations. I am also working with loops, and here the idea of the loop is translated into the exhibition space as visitors to the Neue Nationalgalerie are invited to circle the screens on display.

Time is a recurring protagonist and tool in my work to examine or try to understand the world around us. I often use cinema to move between times, in order to stage an intervention in a real space, confronting the division between public and private, fantasy and reality. This allows me to navigate the past and merge it with present and future desires or preoccupations. I am also working with loops, and here the idea of the loop is translated into the exhibition space as visitors to the Neue Nationalgalerie are invited to circle the screens on display.

Since you mention circles and screens, can you talk about the open air cinema you recently constructed in the demilitarized “Buffer Zone” in Cyprus?

Last summer, after seven years of preparation in collaboration with Point Art Centre for Contemporary Art and the United Nations, I created a circular outdoor cinema in the UN buffer zone of Cyprus, in the deserted so-called Green Line which was introduced in 1974 and still divides the north and south of the island and its communities.

Last summer, after seven years of preparation in collaboration with Point Art Centre for Contemporary Art and the United Nations, I created a circular outdoor cinema in the UN buffer zone of Cyprus, in the deserted so-called Green Line which was introduced in 1974 and still divides the north and south of the island and its communities.

View of Rosa Barba's Inside the Outset: Evoking a Space of Passage, 2021, United Nations Buffer Zone, Deryneia, Cyprus. Open-air cinema. Photo: Marios Stylianou. © Rosa Barba

The circular shape of the cinema’s rammed earth benches, which are integrated in the natural environment, reminds one of an amphitheater, with a permeable metal screen in the middle of it that allows the films to be seen from both sides—all sides. This temporary architectural installation will disappear over time and resume with nature—hopefully after the cinema has fulfilled its purposes of its time and served all the communities on the island.

What drew you to develop a project in this particular location?

I was invited to Cyprus seven years ago by an institution there, Point Art Centre in Nicosia, and I was very intrigued by the border zone and the separation of the island, and that there is no culture shared on both sides. I found this one location, an austere field, where you see a mosque on one side and a church on the other, and I proposed to build an open-air cinema there, where people from both sides could access the same films, without border controls. We tried to find funding and I received then a grant from the Italian Council. I imagined a kind of amphitheater – a circular shape, to come back to the idea of the loop – with a screen at the center. As in my exhibitions, you can see the film from both sides. Because it is the first ever structure since 1974 to be put in that zone, I didn’t want to impose something that would stay forever. It’s made of rammed earth, of earth that is already there. The whole stage is also the seating. The only imposition is the frame with the screen, which can then be taken away.

What drew you to develop a project in this particular location?

I was invited to Cyprus seven years ago by an institution there, Point Art Centre in Nicosia, and I was very intrigued by the border zone and the separation of the island, and that there is no culture shared on both sides. I found this one location, an austere field, where you see a mosque on one side and a church on the other, and I proposed to build an open-air cinema there, where people from both sides could access the same films, without border controls. We tried to find funding and I received then a grant from the Italian Council. I imagined a kind of amphitheater – a circular shape, to come back to the idea of the loop – with a screen at the center. As in my exhibitions, you can see the film from both sides. Because it is the first ever structure since 1974 to be put in that zone, I didn’t want to impose something that would stay forever. It’s made of rammed earth, of earth that is already there. The whole stage is also the seating. The only imposition is the frame with the screen, which can then be taken away.

Rosa Barba, Uncertain Theme – and Therefore Abstract, 2021,

Steel, Glass, Motor, 35 mm film, 123 x 140 x 12,3 cm

Photo Andrea Rossetti © Rosa Barba

Photo Andrea Rossetti © Rosa Barba

Tomorrow you’re opening a new exhibition called Drawing the Infinite. Your show will feature two 35mm film installations, Bending to Earth and From Source to Poem, as well as a selection of sculptural projects made over the past decade. I mentioned abstraction a moment ago, but Bending to Earth (which premiered at the 2015 Venice Biennale) aims a camera at sites where radioactive waste is stored in California, Utah, and Colorado. From a helicopter distance, they appear abstract. But what's the story behind this subject matter? It sounds scary.

![]() Nuclear waste sites seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, Bending to Earth, 2015, 35mm film, color, optical sound; 15 min. Film still © Rosa Barba

Nuclear waste sites seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, Bending to Earth, 2015, 35mm film, color, optical sound; 15 min. Film still © Rosa Barba

Nuclear waste sites seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, Bending to Earth, 2015, 35mm film, color, optical sound; 15 min. Film still © Rosa Barba

Nuclear waste sites seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, Bending to Earth, 2015, 35mm film, color, optical sound; 15 min. Film still © Rosa Barba

In Bending to Earth (2015) I circle different radioactive fields located in desert regions of California, Utah, and Colorado. The film is shot entirely from a helicopter with a handheld camera and brings together a succession of sequences filmed in circles around a selection of constructions used for nuclear waste storage. It’s a whole language, a kind of alphabet that we can no longer decipher, forming an image engineered into the Earth, which will most likely lose its context in the future.

I became interested in inscriptions and social transformations manifested in the landscape in 2006, when I started investigating the desert as an archive of modernity.

An abandoned race track in the Mojave desert, seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, The Open Road, 2010, 35mm film, color, optical sound, 6:14 min. Film still © Rosa Barba

An abandoned race track in the Mojave desert, seen from a helicopter in Rosa Barba, The Open Road, 2010, 35mm film, color, optical sound, 6:14 min. Film still © Rosa Barba Recently the desert has been in communication with astronomy in my work. For example deserts and astronomy share the encounter between old and new technologies, a coming together provoked by how they are used, as happens with deserts, or by the need to see what is not within sight, as is the case with astronomy. This relationship between the environment-as-document and the machine, mainly the machine of vision, together with a complex conception of time generated by the timelessness of vast spaces without geographical limits has led me to propose works of an enigmatic nature, works of a certain opacity, that address the transformations of society and the changing ways in which we relate to it.

Your gallery exhibitions are described as following the principle of cinematic montage. What does the principle of montage mean for you as an artist working in the way that you do? Can you talk a little bit about how it informs your approach to making films, publications, or exhibitions?

I regard cinema in an architectural sense, and as an instrument where the environment, the screen, and the projection can be combined or pushed forward to create another spatiotemporal dimension which is concurrent with and points beyond the context of interior or exterior space. So montage here also means experimenting with time-based forms, where I expand their potential to become not only sculptural objects, installations or architectural sites but also speculations, in an ever-changing process of transformation.

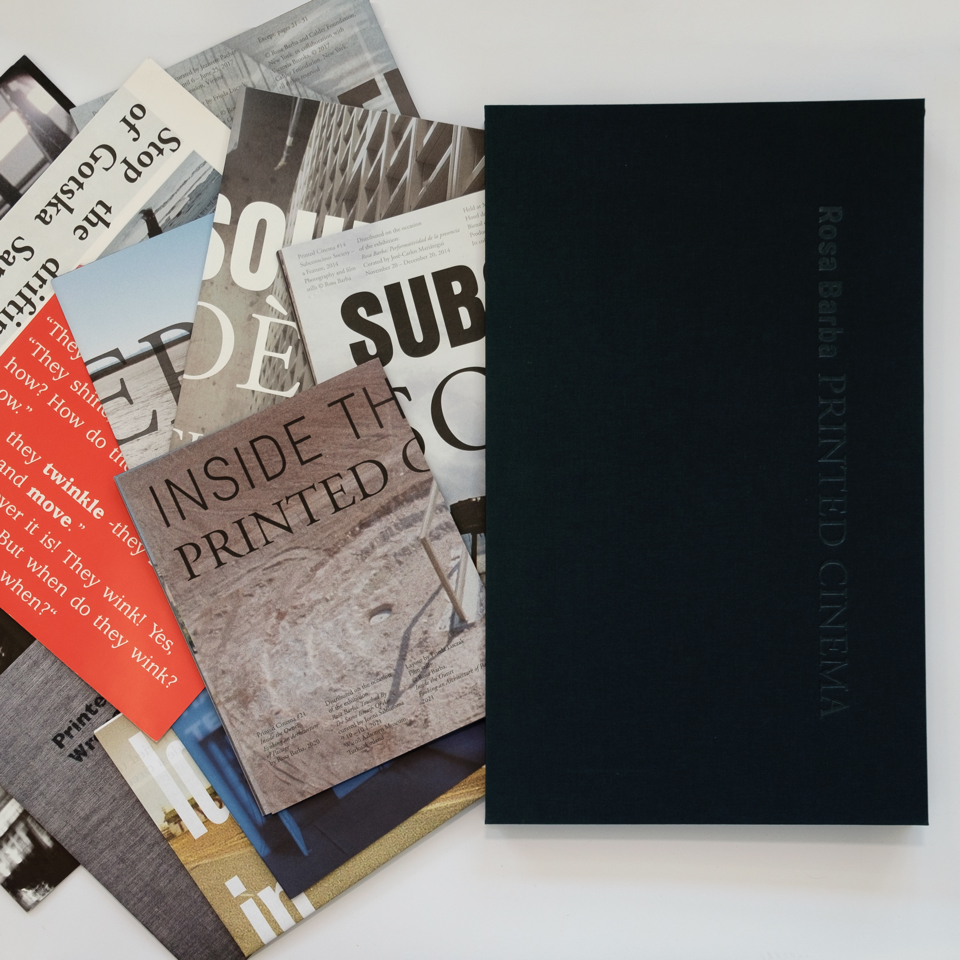

The publication project Printed Cinema continues my audiovisual work as a personal reflection on the essence of the cinematographic. Here too images are articulated in the space in between images. Gaps, ellipses, and the dialectics between images—essentially modernist notions—are crucial in that respect. In Printed Cinema, this is expressed in the editing principle, as well as in the oppositions between film and printing, between text and image. The specific distribution method, of course, extends the project into a wide range of cultural and social contexts. In this way, Printed Cinema challenges the outer edges of the artist’s book. Mechanisms proper to the film medium find their translation in a different context.

It is a proposition of a readable and portable film in order to express and dismantle the cinematic organism in extended free-form experiments in word and image that can be encountered alongside cinematic experiences or stand on their own. The shift in medium from projection to print emphasized the difference of such experiences of image and text, exposing their relationships, overlaps and hierarchies.

I regard cinema in an architectural sense, and as an instrument where the environment, the screen, and the projection can be combined or pushed forward to create another spatiotemporal dimension which is concurrent with and points beyond the context of interior or exterior space. So montage here also means experimenting with time-based forms, where I expand their potential to become not only sculptural objects, installations or architectural sites but also speculations, in an ever-changing process of transformation.

The publication project Printed Cinema continues my audiovisual work as a personal reflection on the essence of the cinematographic. Here too images are articulated in the space in between images. Gaps, ellipses, and the dialectics between images—essentially modernist notions—are crucial in that respect. In Printed Cinema, this is expressed in the editing principle, as well as in the oppositions between film and printing, between text and image. The specific distribution method, of course, extends the project into a wide range of cultural and social contexts. In this way, Printed Cinema challenges the outer edges of the artist’s book. Mechanisms proper to the film medium find their translation in a different context.

It is a proposition of a readable and portable film in order to express and dismantle the cinematic organism in extended free-form experiments in word and image that can be encountered alongside cinematic experiences or stand on their own. The shift in medium from projection to print emphasized the difference of such experiences of image and text, exposing their relationships, overlaps and hierarchies.

Okay this one’s going in a different direction, but if you were to travel to outer space and could take only three movies with you, for your own enjoyment or to share with extraterrestrials, which three movies would you take?

At this moment I would suggest:

![]() Me and My Brother (Robert Frank, 1965–1968)

Me and My Brother (Robert Frank, 1965–1968)

![]() Saute ma ville (Chantal Akerman, 1968)

Saute ma ville (Chantal Akerman, 1968)

![]() The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (Werner Herzog, 1974)

The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (Werner Herzog, 1974)

An exhibition of Rosa Barba’s work opens on April 6 at Luhring Augustine in Tribeca, New York City, and will be on view until May 21st.

Rosa Barba has had recent solo exhibitions at Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin; MIT List Visual Art Center, Cambridge, MA; and Pirelli HangarBiCocca, Milan. Her work is in the permanent collections of Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate Modern, London; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; Jumex Collection, Mexico City; Louis Vuitton Collection, Paris; among many others. She is a recent winner of The Calder Prize, Calder Foundation, New York, and has had several international residencies. Two new books on Barba’s work have recently been published: Rosa Barba: On the Anarchic Organization of Cinematic Spaces, 2021 by Hatje Cantz, and a limited edition boxed set of her Printed Cinema publications, just released with Dancing Foxes Press, Brooklyn.