Andrew Dosunmu

Interview by Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Thomas: As an artist you’ve worked in many ways, in fashion, still photography, art direction, music videos, and cinema. You started out as a design assistant at the fashion house of Yves Saint Laurent in Paris, and I was wondering what it was like to be in that kind of space as an emerging artist?

Andrew Dosunmu: I think almost by default as a young person you’re attracted to images, and fashion images were more accessible for some reason. As a young kid, magazines like Details, Interview, iD, were accessible to me, and I think that’s what sort of got me into fashion.

So you came into fashion through fashion photography?

Yes, because what I really liked were images, and these images were associated with fashion. I didn’t know anyone who was a photographer or filmmaker — it’s not like now, where you have some cousin, or uncle, or relative involved in these things. I came from a different kind of world, growing up in Nigeria. So I was looking at these magazines, which drew me to images, and that’s what drew me into fashion. And then, working as a design assistant was amazing. It made me realize that it’s not actually fashion that I liked. It’s more the world of the images. What was beautiful about working at Yves Saint Laurent was that half of the job was about research, and in that process of research was going out to museums. I spent most of my time there going to Centre Pompidou, looking at images, because you’re doing research on the 1940s or something.

Because the research would contribute to the design of clothing?

Exactly, because the research was about the era, and I think that researching eras helped me realize that it wasn’t fashion that I liked, but it was the idea of a world that I liked. I’ve always been very fascinated by wondering what it’s like before and after the picture I’m looking at was taken. What was that world like? What does that room smell like? What did that person eat? This is what I mean by the world of the image.

And then, not speaking French before I went to France, I learned French from watching movies. My first year in France I didn’t want to do what everyone did, which is go to Al liance Française and learn French. I think I went to Alliance Française for like one day. It was just so complicated for me, so I went to the cinema a lot and watched a lot of films. Most of the time I went to the movies because a lot of the foreign films were translated into French, so I learned French through that process, and through that process I got to see a lot of world cinema. Because France was very good for that. You could wake up at 9am and go to the movies, you know? And you can see movies from different parts of the world, whether it’s Romanian films, or Czech films, or Indian films. It was so beautiful. In France you’ve got things like Festival de Cinema, or Jour de Cinema, where in one day you can see as many films as you want for the equivalent of one dollar. It’s the combination of all that that brought me into filmmaking.

So you’re in Paris working at Yves Saint Laurent, doing research, and going to the movies. Did you meet any filmmakers in that context?

I never met a filmmaker at that time. But the combination of doing this research for Yves Saint Laurant and going to the movies to learn French made me realize that what I really wanted to do was become an image-maker. As a kid growing up in a different part of the world, the notion of having a career as an image-maker was not that accessible, let’s put it that way. Or maybe there was someone you knew who was involved with making images, but they were so far away. Especially in Nigeria itself. Like the theater world. You knew about New York theaters, you knew about theater troops and plays and things like that, but the idea of making theater was something quite foreign.

At what point did you start carrying a camera around with you? What was your path to photography and film?

I wanted to be a filmmaker, but I forgot to go to film school, so that was out of the process. I bought a super-8 camera at a flea market and I started making these short films with my friends, like Xuly.Bët, on the weekends. We’d throw a party and project them for friends, with a super-8 projector. That’s how I really started. My first commission came when someone saw one of these films and invited me and my friend Xuly.Bët to do a short for the aniversary of Gitanes, the French cigarette.

How do you spell your friend’s name?

Xuly.Bët, which means “keep your eyes open” in Wolof.

He’s from Senegal?

Yes, he’s a Senegalese designer who’s very well known in France now. He was like this enfant terrible among young designers in France — he was buying clothes from the flea market and recycling them and making them into new forms. He became quite known. So Gitanes commissioned us to do this film…

What year was this?

Hmm, late-90s, maybe early 2000s. We went to Dakar and made this short film, which is a beautiful short, now that I look back at it. And that’s how it started.

Looking back, it seems like you were active in making photographs before making films?

Yes, I was.

Andrew Dosunmu: I think almost by default as a young person you’re attracted to images, and fashion images were more accessible for some reason. As a young kid, magazines like Details, Interview, iD, were accessible to me, and I think that’s what sort of got me into fashion.

So you came into fashion through fashion photography?

Yes, because what I really liked were images, and these images were associated with fashion. I didn’t know anyone who was a photographer or filmmaker — it’s not like now, where you have some cousin, or uncle, or relative involved in these things. I came from a different kind of world, growing up in Nigeria. So I was looking at these magazines, which drew me to images, and that’s what drew me into fashion. And then, working as a design assistant was amazing. It made me realize that it’s not actually fashion that I liked. It’s more the world of the images. What was beautiful about working at Yves Saint Laurent was that half of the job was about research, and in that process of research was going out to museums. I spent most of my time there going to Centre Pompidou, looking at images, because you’re doing research on the 1940s or something.

Because the research would contribute to the design of clothing?

Exactly, because the research was about the era, and I think that researching eras helped me realize that it wasn’t fashion that I liked, but it was the idea of a world that I liked. I’ve always been very fascinated by wondering what it’s like before and after the picture I’m looking at was taken. What was that world like? What does that room smell like? What did that person eat? This is what I mean by the world of the image.

And then, not speaking French before I went to France, I learned French from watching movies. My first year in France I didn’t want to do what everyone did, which is go to Al liance Française and learn French. I think I went to Alliance Française for like one day. It was just so complicated for me, so I went to the cinema a lot and watched a lot of films. Most of the time I went to the movies because a lot of the foreign films were translated into French, so I learned French through that process, and through that process I got to see a lot of world cinema. Because France was very good for that. You could wake up at 9am and go to the movies, you know? And you can see movies from different parts of the world, whether it’s Romanian films, or Czech films, or Indian films. It was so beautiful. In France you’ve got things like Festival de Cinema, or Jour de Cinema, where in one day you can see as many films as you want for the equivalent of one dollar. It’s the combination of all that that brought me into filmmaking.

So you’re in Paris working at Yves Saint Laurent, doing research, and going to the movies. Did you meet any filmmakers in that context?

I never met a filmmaker at that time. But the combination of doing this research for Yves Saint Laurant and going to the movies to learn French made me realize that what I really wanted to do was become an image-maker. As a kid growing up in a different part of the world, the notion of having a career as an image-maker was not that accessible, let’s put it that way. Or maybe there was someone you knew who was involved with making images, but they were so far away. Especially in Nigeria itself. Like the theater world. You knew about New York theaters, you knew about theater troops and plays and things like that, but the idea of making theater was something quite foreign.

At what point did you start carrying a camera around with you? What was your path to photography and film?

I wanted to be a filmmaker, but I forgot to go to film school, so that was out of the process. I bought a super-8 camera at a flea market and I started making these short films with my friends, like Xuly.Bët, on the weekends. We’d throw a party and project them for friends, with a super-8 projector. That’s how I really started. My first commission came when someone saw one of these films and invited me and my friend Xuly.Bët to do a short for the aniversary of Gitanes, the French cigarette.

How do you spell your friend’s name?

Xuly.Bët, which means “keep your eyes open” in Wolof.

He’s from Senegal?

Yes, he’s a Senegalese designer who’s very well known in France now. He was like this enfant terrible among young designers in France — he was buying clothes from the flea market and recycling them and making them into new forms. He became quite known. So Gitanes commissioned us to do this film…

What year was this?

Hmm, late-90s, maybe early 2000s. We went to Dakar and made this short film, which is a beautiful short, now that I look back at it. And that’s how it started.

Looking back, it seems like you were active in making photographs before making films?

Yes, I was.

That image was published in BIG magazine, which has been around for two or three decades now. They were actually one of the pioneers of magazines like Document Journal, and were sort of competing with a magazine called Visionaire, in its early days. They were fashion magazines, but not your typical fashion magazines like Vogue. It was more curated, and more about images, in a way.

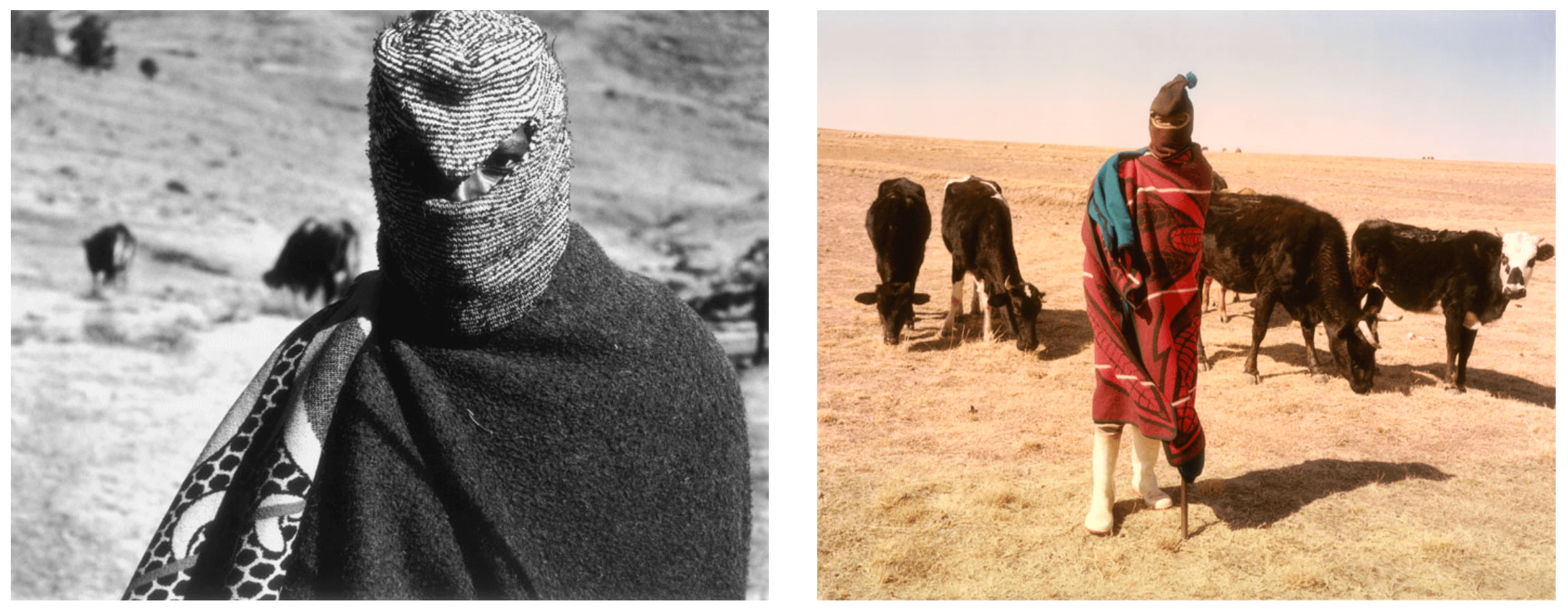

These are from one of my personal projects. They were shot in Losotho, one of the countries in the southern tip of Africa, where it snows. It’s interesting because it gets very cold and it’s amazing when you see all the young kids and how they dress, which I find very fascinating. They ski there with self-made boards.

You called this a personal project. I wonder what you mean? How did you end up in Losotho?

I travel a lot, photographically. I backpack in different parts of the world and take pictures. And I’ve always been fascinated about Losotho, because it snows. I was trying to do a film project there, so I was doing research. And while doing research I ran into these guys and just started photographing them.

I read that the Kingdom of Losotho, which is geographically tucked away, was one of the inspirations for Wakanda.

I heard that later on.

You were taking these photos between 2009-2012?

Yes, I’ve got a whole bunch of these photos that are yet to be released.

![]()

Is this from the same series?

No that’s completely different. That was shot in West Africa. That’s the masquerade, the Egungun, which is a Yoruba masquerade that is believed to be the contact between humans and the life beyond. This is the communicator between the living and the dead. He’s the one that can see beyond, to the life after.

Where in West Africa was this?

The Yoruba region, which is from the Southwest part of Nigeria to the Benin Republic, all the way to Togo. Anywhere there’s the Yoruba lineage, the Yoruba tribe.

Are the textiles unique to the social function that person performs?

Absolutely. They’re known for that. It’s often a festival that happens at a specific time in the season. And the Egun, to be a part of that you have to belong to a certain lineage of family. It’s sort of like a griot; a griot is a singer. The Egungun is a most spiritial connection to the Yoruba dieties, and the figure you see here is the one who communicates with the life beyond.

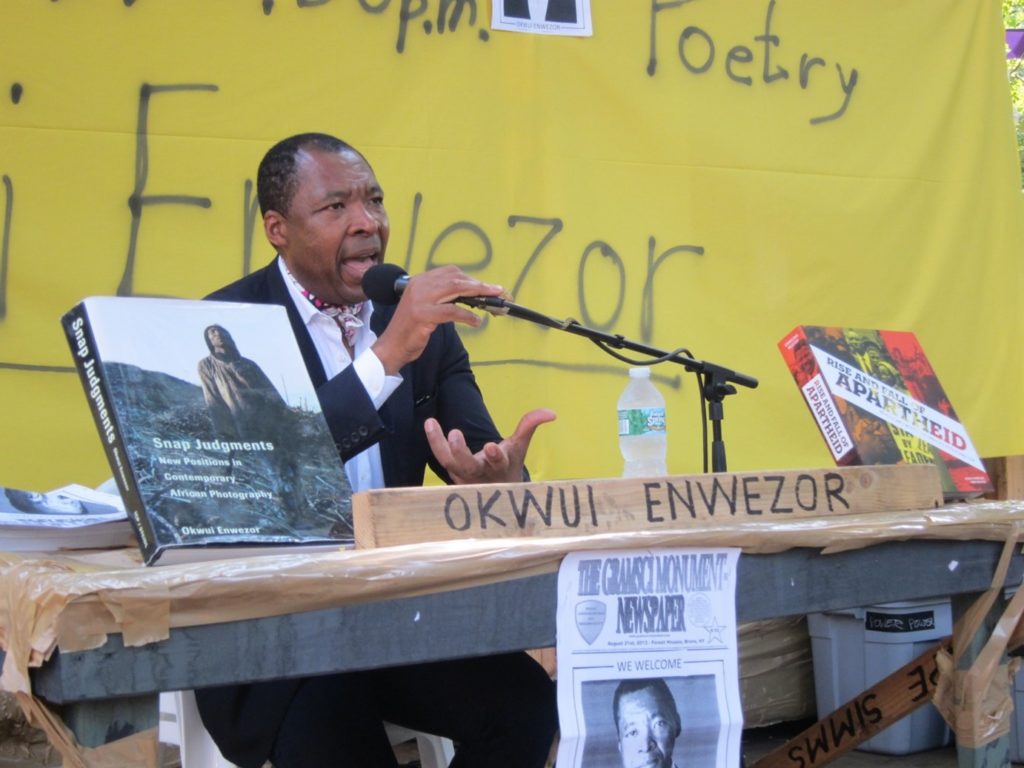

In the 1990s you were active directing music videos for musicians like Isaac Hayes and Common, but I wanted to ask about something that came a bit later. In 2006, your work was included in the exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, curated by Okwui Enwezor for the ICP in New York. What was it like meeting Okwui Enwezor?

![Renowned curator Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019). Photo: Andreas Gebert]()

![Okwui Enwezor, "Poetry Session" at the Gramsci Monument by Thomas Hirschhorn, Forest Houses, Bronx, New York (2013). Photo: Romain Lopez]()

Okwui was a brilliant mind. He was just someone who understood. As an image maker, I was creating this world that I understood but maybe most people don’t. With Okwui it was the first time I connected with someone who was able to word it.

I remember we talked about so many things. We had all these projects we wanted to make on film, because we could relate. We talked about the DRUM magazines of the 1950s, or the DRUM magazines of 60s and 70s, that were published across West Africa. We talked about the aesthetics of that specific generation. It was really beautiful to connect with someone for whom you didn’t have to explain those references, because they were perfectly influenced by those references at one point in their life. It’s almost like we spoke the same language, so there was no need for explanation. If anything, he was able to shed light, and expose you to more stuff that he knew was in your realm. That was beautiful, wonderful, and very rare for me at that point — to meet somebody who knew what I was trying to do, who knew the world I was trying to create, because this world was in my head.

Do you remember what you showed in Snap Judgments?

Yes. Okwui came by my studio and selected a collection of stuff, if I remember: there were some pictures that I shot in Brooklyn, in Crown Heights — it was a fashion story actually that was commissioned by a brilliant art director, Phil Bicker, who worked at The Face magazine in the 90s. Then he moved to America in the 2000s. Phil was the art director of a magazine called Black Book. He gave me my first commission, actually. It was a fashion story called “Pulp Fiction.” So Okwui took some work from there, and some portraits I shot Jamaica. It was a bunch of stuff. He just came to my studio and curated it. I rememebr he did a wall of my pictures. It was the only wall where there were no framed pictures, there were just pinned pictures. The other works were all framed. I think it was the way he saw my work, almost like a collage on the wall.

It was his idea to pin them instead of frame them?

Yes. It was a black wall with all these pictures, and then there was a screen at the bottom where I was showing videos.

So that was 2006.

Yes, and before we go any further I should say that photography was default for me. It was film that I wanted to make, but it was so expensive. You have to understand that I came into film and fashion almost like a nomad in a way, because I just wandered to it. I didn’t know anyone. There was no one I knew as a friend who made films. The closest thing I had was super-8, so I filmed on super-8, developed them, edited them myself with splices, glued them, and projected them.

Photography came by default because I realized making films was too expensive. I could only make these little films. And even shooting on super-8 was expensive in a way — you have to buy the film, develop it, and all that stuff. So the way photography became the default is that I realized that if I take pictures I will record everything I would like to film one day. That’s how photography came.

Has photography always been one step in the direction of cinema?

Absolutely. It was a scrapbook for me. It was like my diary.

Do you still do that when you make films today?

Yes, most things I take pictures of are things I would eventually like to film, because that’s how I got into photography. I just thought one day I’ll eventually put all these together in a film. Normally people take pictures and then they become filmmakers. I was a filmmaker who wanted to make films and pictures were secondary. It was just a way for me to maintain making films without making films, because it was expensive.

You called this a personal project. I wonder what you mean? How did you end up in Losotho?

I travel a lot, photographically. I backpack in different parts of the world and take pictures. And I’ve always been fascinated about Losotho, because it snows. I was trying to do a film project there, so I was doing research. And while doing research I ran into these guys and just started photographing them.

I read that the Kingdom of Losotho, which is geographically tucked away, was one of the inspirations for Wakanda.

I heard that later on.

You were taking these photos between 2009-2012?

Yes, I’ve got a whole bunch of these photos that are yet to be released.

Is this from the same series?

No that’s completely different. That was shot in West Africa. That’s the masquerade, the Egungun, which is a Yoruba masquerade that is believed to be the contact between humans and the life beyond. This is the communicator between the living and the dead. He’s the one that can see beyond, to the life after.

Where in West Africa was this?

The Yoruba region, which is from the Southwest part of Nigeria to the Benin Republic, all the way to Togo. Anywhere there’s the Yoruba lineage, the Yoruba tribe.

Are the textiles unique to the social function that person performs?

Absolutely. They’re known for that. It’s often a festival that happens at a specific time in the season. And the Egun, to be a part of that you have to belong to a certain lineage of family. It’s sort of like a griot; a griot is a singer. The Egungun is a most spiritial connection to the Yoruba dieties, and the figure you see here is the one who communicates with the life beyond.

In the 1990s you were active directing music videos for musicians like Isaac Hayes and Common, but I wanted to ask about something that came a bit later. In 2006, your work was included in the exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, curated by Okwui Enwezor for the ICP in New York. What was it like meeting Okwui Enwezor?

Okwui was a brilliant mind. He was just someone who understood. As an image maker, I was creating this world that I understood but maybe most people don’t. With Okwui it was the first time I connected with someone who was able to word it.

I remember we talked about so many things. We had all these projects we wanted to make on film, because we could relate. We talked about the DRUM magazines of the 1950s, or the DRUM magazines of 60s and 70s, that were published across West Africa. We talked about the aesthetics of that specific generation. It was really beautiful to connect with someone for whom you didn’t have to explain those references, because they were perfectly influenced by those references at one point in their life. It’s almost like we spoke the same language, so there was no need for explanation. If anything, he was able to shed light, and expose you to more stuff that he knew was in your realm. That was beautiful, wonderful, and very rare for me at that point — to meet somebody who knew what I was trying to do, who knew the world I was trying to create, because this world was in my head.

Do you remember what you showed in Snap Judgments?

Yes. Okwui came by my studio and selected a collection of stuff, if I remember: there were some pictures that I shot in Brooklyn, in Crown Heights — it was a fashion story actually that was commissioned by a brilliant art director, Phil Bicker, who worked at The Face magazine in the 90s. Then he moved to America in the 2000s. Phil was the art director of a magazine called Black Book. He gave me my first commission, actually. It was a fashion story called “Pulp Fiction.” So Okwui took some work from there, and some portraits I shot Jamaica. It was a bunch of stuff. He just came to my studio and curated it. I rememebr he did a wall of my pictures. It was the only wall where there were no framed pictures, there were just pinned pictures. The other works were all framed. I think it was the way he saw my work, almost like a collage on the wall.

It was his idea to pin them instead of frame them?

Yes. It was a black wall with all these pictures, and then there was a screen at the bottom where I was showing videos.

So that was 2006.

Yes, and before we go any further I should say that photography was default for me. It was film that I wanted to make, but it was so expensive. You have to understand that I came into film and fashion almost like a nomad in a way, because I just wandered to it. I didn’t know anyone. There was no one I knew as a friend who made films. The closest thing I had was super-8, so I filmed on super-8, developed them, edited them myself with splices, glued them, and projected them.

Photography came by default because I realized making films was too expensive. I could only make these little films. And even shooting on super-8 was expensive in a way — you have to buy the film, develop it, and all that stuff. So the way photography became the default is that I realized that if I take pictures I will record everything I would like to film one day. That’s how photography came.

Has photography always been one step in the direction of cinema?

Absolutely. It was a scrapbook for me. It was like my diary.

Do you still do that when you make films today?

Yes, most things I take pictures of are things I would eventually like to film, because that’s how I got into photography. I just thought one day I’ll eventually put all these together in a film. Normally people take pictures and then they become filmmakers. I was a filmmaker who wanted to make films and pictures were secondary. It was just a way for me to maintain making films without making films, because it was expensive.

Restless City was shot in 2010 and released in 2011 as your debut feature. To my understanding you had already been developing Mother of George for some time and finally got tired of waiting for the money and made Restless City instead, which makes Restless City a beautiful document of creative necessity. This film also debuts your filmmaking collaborations with the cinematographer Bradford Young, and costume designer Mobolaji Dawodu. What was it about Restless City that made it feel necessary to you, as the story you wanted to tell at that moment?

Well, to go back to what you said a moment ago about the influence of clothing in my films, I think every filmmaker comes from a different path. That’s my strength. It’s the background of all the things I’ve been involved in, which influence who I am — being a photographer, working in fashion: those are my strengths and I try to embrace them. Some filmmakers come from a writing background, and you can really tell in their films. I come from a different world and I try to embrace all those elements when filmmaking, whether it’s production design, cinematography, costumes — I really try to use all those things equally as a filmmaker. I pay particular attention to that. Everyone has an equal role, which is unlike most filmmakers, where it’s really about the dialogue.

For me cinema is a visual medium first and foremost, and that’s what I want to embrace. The last thing I want is for my film to be lost in translation. I really want every viewer, every audience in any part of the world, to understand my films visually. Hopefully the dialogue enhances it, but I do not want them to not get it for lack of translation.

As for my collaborations, Mobolaji is somebody who has worked with me the most times. He was actually once my assistant, to be honest. He’s in charge of costumes, and used to do that for my photographs. Since he had been working with me as my assistant and has been around me for so long, I said “Why don’t you do this?” He was never someone who wanted to do it, but I was like: “You know you can do this, right? You could really do this — you’ve got what it takes. You know?” I just wanted to be there to support him.

What was it that he had, that caught your attention?

When I met him he wasn’t doing this at all. He was an extra in one of my videos. He embodied something that I liked, he embodied a style. It’s not necessarily what he wore, it’s just the way one carries something. It’s the essence that I really liked. By the time I made Restless City, I knew he could do it.

What does “it” entail in this context, for someone who plays this particular role in the making of your films?

For me, it entails someone who is worldly and can navigate different worlds, who can understand the essence of being in different worlds as a traveler. Someone who you can drop in Timbuktu tomorrow and they will navigate their way, you know? Make friends, communicate with them — it’s beyond the clothes. The clothes are secondary. How can you communicate? How can you navigate different worlds, and easily be as comfortable?

Mobolaji is one person I know can do that. I can send him anywhere in the world and he probably doesn’t speak the language or look like the people, but he can navigate and be comfortable. To come back to Restless City, that’s what the Djibril character is about for me.

Well, to go back to what you said a moment ago about the influence of clothing in my films, I think every filmmaker comes from a different path. That’s my strength. It’s the background of all the things I’ve been involved in, which influence who I am — being a photographer, working in fashion: those are my strengths and I try to embrace them. Some filmmakers come from a writing background, and you can really tell in their films. I come from a different world and I try to embrace all those elements when filmmaking, whether it’s production design, cinematography, costumes — I really try to use all those things equally as a filmmaker. I pay particular attention to that. Everyone has an equal role, which is unlike most filmmakers, where it’s really about the dialogue.

For me cinema is a visual medium first and foremost, and that’s what I want to embrace. The last thing I want is for my film to be lost in translation. I really want every viewer, every audience in any part of the world, to understand my films visually. Hopefully the dialogue enhances it, but I do not want them to not get it for lack of translation.

As for my collaborations, Mobolaji is somebody who has worked with me the most times. He was actually once my assistant, to be honest. He’s in charge of costumes, and used to do that for my photographs. Since he had been working with me as my assistant and has been around me for so long, I said “Why don’t you do this?” He was never someone who wanted to do it, but I was like: “You know you can do this, right? You could really do this — you’ve got what it takes. You know?” I just wanted to be there to support him.

What was it that he had, that caught your attention?

When I met him he wasn’t doing this at all. He was an extra in one of my videos. He embodied something that I liked, he embodied a style. It’s not necessarily what he wore, it’s just the way one carries something. It’s the essence that I really liked. By the time I made Restless City, I knew he could do it.

What does “it” entail in this context, for someone who plays this particular role in the making of your films?

For me, it entails someone who is worldly and can navigate different worlds, who can understand the essence of being in different worlds as a traveler. Someone who you can drop in Timbuktu tomorrow and they will navigate their way, you know? Make friends, communicate with them — it’s beyond the clothes. The clothes are secondary. How can you communicate? How can you navigate different worlds, and easily be as comfortable?

Mobolaji is one person I know can do that. I can send him anywhere in the world and he probably doesn’t speak the language or look like the people, but he can navigate and be comfortable. To come back to Restless City, that’s what the Djibril character is about for me.

By the time he came to America he’s lived through four different continents, and probably spoke the languages of all those continents. That’s what he embodied. So the story of Djibril is not simply that of being an immigrant, it’s how he navigates and communicates, and how he’s a modern person, you know? He’s the epitome of a modern person. He’s equally as comfortable in Oklahoma as he would be in Helsinki. He’s not intimidated by anything.

When I got to make that film, there was something really amazing about being naive. Once you’re part of a structure, you know what to avoid. It’s the fact of not knowing, of making those mistakes that are beautiful, that if you had known you wouldn’t have made them — whether you overexpose or underexpose the film, or the speed is not right. In that process you discover things. Those things are what’s so beautiful about being naive, and what with knowledge you let go of, because you know what’s going to happen. There’s something about that that I try to hold on to. Obviously you learn and you are aware, but those accidental mistakes are so beautiful.

When I made Restless City I just wanted to learn from having to make a film. The same with Mother of George. And there was also a beautiful film I was trying to make called Girls at War, which was an adaptation of Chinua Achebe’s short story, and I went through that process of waiting and waiting, and having producers involved, and getting development funds, and yet it never got made.

Everyone wants perfection — the perfect script — but I don’t know what that means. 90% of Hollywood movies are supposed to be perfect scripts when they’re greenlit, and they’re all disasters, as we know. So what’s a perfect script? Having been through that process once or twice, whether it’s Mother of George or Girls at War, and being at a point where I was getting to know filmmakers, and knowing that process they go through or waiting-waiting-waiting, I realized that, for me, I should be making films and learning from my mistakes, not waiting for money. So that’s what initiated Restless City.

When I got to make that film, there was something really amazing about being naive. Once you’re part of a structure, you know what to avoid. It’s the fact of not knowing, of making those mistakes that are beautiful, that if you had known you wouldn’t have made them — whether you overexpose or underexpose the film, or the speed is not right. In that process you discover things. Those things are what’s so beautiful about being naive, and what with knowledge you let go of, because you know what’s going to happen. There’s something about that that I try to hold on to. Obviously you learn and you are aware, but those accidental mistakes are so beautiful.

When I made Restless City I just wanted to learn from having to make a film. The same with Mother of George. And there was also a beautiful film I was trying to make called Girls at War, which was an adaptation of Chinua Achebe’s short story, and I went through that process of waiting and waiting, and having producers involved, and getting development funds, and yet it never got made.

Everyone wants perfection — the perfect script — but I don’t know what that means. 90% of Hollywood movies are supposed to be perfect scripts when they’re greenlit, and they’re all disasters, as we know. So what’s a perfect script? Having been through that process once or twice, whether it’s Mother of George or Girls at War, and being at a point where I was getting to know filmmakers, and knowing that process they go through or waiting-waiting-waiting, I realized that, for me, I should be making films and learning from my mistakes, not waiting for money. So that’s what initiated Restless City.

Restless City opens with an epigraph by Cyprian Ekwensi. Is this an author who was important for you?

Very important. Cyprian Ekwensi is probably the first postcolonial writer to publish full-length fiction. I think he was before Achebe. He wrote a book called Jaguar Nana (1961).

Very important. Cyprian Ekwensi is probably the first postcolonial writer to publish full-length fiction. I think he was before Achebe. He wrote a book called Jaguar Nana (1961).

He was from Nigeria?

Yes. He wrote an amazing book called Restless City and Christmas Gold (1975) — Restless City was almost like my homage to that book, as the book I would have liked to have made — it’s a collection of short stories that were set during the Christmas season and everyone’s hurry to have everything for the holidays. What I loved was this drive of people who come to Lagos, everybody coming to make it. It’s an amazing collection of short stories and it really meant a lot to me.

How did you first meet up with Bradford Young?

When Bradford was in college he knew a bunch of my videos and pictures, because I was shooting a lot then for Fader. When we met, it was just a connection.

You met in New York?

Yes, and it was beautiful, because, like Okwui, we understood the same things and had the same references. When we met, we just clicked. When I think about Brad, and Mobolaji, I think of us being a band, like the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Fishbone. One of us is the drummer, one is the bass player, and that’s how I look at it. It’s shorthand. When I talk about the red color of Shango, the Yoruba diety, he understood easily. Or the depths of the streets of Timbuktu. Or the blue-black in the Delta. What the sun feels like on dark skin in the Delta at a certain time. It’s just an amazing connection that is inherited, really. It’s not something you learn. How did the Chili Peppers get together? or how did a band like Fishbone get together? You meet each other and just connect, and say oh yeah, let’s jam. You don’t even think about it before you realize, you’re in a band together. I think that’s what it is with these guys. That’s the best way I can put it. We just happen to be a bunch of kids who jammed together and then realized we’re in a band, we are a band, you know?

Yes. He wrote an amazing book called Restless City and Christmas Gold (1975) — Restless City was almost like my homage to that book, as the book I would have liked to have made — it’s a collection of short stories that were set during the Christmas season and everyone’s hurry to have everything for the holidays. What I loved was this drive of people who come to Lagos, everybody coming to make it. It’s an amazing collection of short stories and it really meant a lot to me.

How did you first meet up with Bradford Young?

When Bradford was in college he knew a bunch of my videos and pictures, because I was shooting a lot then for Fader. When we met, it was just a connection.

You met in New York?

Yes, and it was beautiful, because, like Okwui, we understood the same things and had the same references. When we met, we just clicked. When I think about Brad, and Mobolaji, I think of us being a band, like the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Fishbone. One of us is the drummer, one is the bass player, and that’s how I look at it. It’s shorthand. When I talk about the red color of Shango, the Yoruba diety, he understood easily. Or the depths of the streets of Timbuktu. Or the blue-black in the Delta. What the sun feels like on dark skin in the Delta at a certain time. It’s just an amazing connection that is inherited, really. It’s not something you learn. How did the Chili Peppers get together? or how did a band like Fishbone get together? You meet each other and just connect, and say oh yeah, let’s jam. You don’t even think about it before you realize, you’re in a band together. I think that’s what it is with these guys. That’s the best way I can put it. We just happen to be a bunch of kids who jammed together and then realized we’re in a band, we are a band, you know?

You mentioned Red Hot Chili Peppers and Fishbone, and elsewhere you’ve compared making movies to jazz. There was this little moment that jumped out when I was going through your work this week. It wasn’t shot by Bradford Young, but it’s a nice example of musical form.

Transitional sequences like this are a quality I would highlight in your work. This example is from your documentary Untethered: The David Brown Story, which is about the world’s fastest blind sprinter, David Brown, and his guide runner, Jerome Avery. How did this project come about?

![]()

![]()

An Australian art director wanted to make this film and they approached me, and I loved the subject matter, the human story. I mean he’s amazing. I’ve got hours and hours of footage of him, and it’s so inspiring to see someone like him doing what he loves. It’s just incredible, for lack of a better word.

I just wanted to be with him, and it’s a documentary, so I didn’t want to influence it other than where I wanted him to go and what I wanted to shoot, you know what I’m saying? I just wanted to be with him, and express my love for him through the way I photograph him. It’s not like a script that I wrote. All I could say to him is “I’d love to shoot you on the Staten Island Ferry, or in the New York subway.” I knew he had never been to New York. For someone who’s never been to New York, what are the things that he’s heard about, but probably had never seen? So I picked all those things. Like wouldn’t it be nice to go to the Statue of Liberty, and ride on this ferry, and then I think about the early migration to the States, to America, and coming from Ellis Island, and all that travel through the city. Those are the things I was thinking about and I wanted to go to places that could be described to him, places we’ve all heard of, but he hasn’t seen.

That scene you showed with Black Thought, that was Black Thought of the Roots who was holding his hand. There he is with a musician, you know? They’re connected. What’s that connection like? Whether you’re a musician or a listener … that’s what so beautiful about music universally. How do you connect to it? When I hear Romanian Gypsy songs, or Jessye Norman performing Strauss, there’s something that connects me to it. I don’t even understand it. It’s an emotional connection, it’s feelings, it’s what music does, it’s that universal connection of sound. How it evokes something emotionally. I think that’s what I want my films to be — to evoke things emotionally. Not necessarily through dialogue, but I hope that through my assortment of images, for lack of a better word, you know? I’m able to evoke something that is even beyond me. I don’t even know what I’m evoking, but I’m evoking something. I don’t really have to understand my themes but I hope that every time I watch it I understand it more, because it’s a feeling and sometimes you might not be able to express feelings, or have the right verbs for certain ways or certain things. I hope I’m learning through them. Perfection by no means is what I’m looking for.

An Australian art director wanted to make this film and they approached me, and I loved the subject matter, the human story. I mean he’s amazing. I’ve got hours and hours of footage of him, and it’s so inspiring to see someone like him doing what he loves. It’s just incredible, for lack of a better word.

I just wanted to be with him, and it’s a documentary, so I didn’t want to influence it other than where I wanted him to go and what I wanted to shoot, you know what I’m saying? I just wanted to be with him, and express my love for him through the way I photograph him. It’s not like a script that I wrote. All I could say to him is “I’d love to shoot you on the Staten Island Ferry, or in the New York subway.” I knew he had never been to New York. For someone who’s never been to New York, what are the things that he’s heard about, but probably had never seen? So I picked all those things. Like wouldn’t it be nice to go to the Statue of Liberty, and ride on this ferry, and then I think about the early migration to the States, to America, and coming from Ellis Island, and all that travel through the city. Those are the things I was thinking about and I wanted to go to places that could be described to him, places we’ve all heard of, but he hasn’t seen.

That scene you showed with Black Thought, that was Black Thought of the Roots who was holding his hand. There he is with a musician, you know? They’re connected. What’s that connection like? Whether you’re a musician or a listener … that’s what so beautiful about music universally. How do you connect to it? When I hear Romanian Gypsy songs, or Jessye Norman performing Strauss, there’s something that connects me to it. I don’t even understand it. It’s an emotional connection, it’s feelings, it’s what music does, it’s that universal connection of sound. How it evokes something emotionally. I think that’s what I want my films to be — to evoke things emotionally. Not necessarily through dialogue, but I hope that through my assortment of images, for lack of a better word, you know? I’m able to evoke something that is even beyond me. I don’t even know what I’m evoking, but I’m evoking something. I don’t really have to understand my themes but I hope that every time I watch it I understand it more, because it’s a feeling and sometimes you might not be able to express feelings, or have the right verbs for certain ways or certain things. I hope I’m learning through them. Perfection by no means is what I’m looking for.

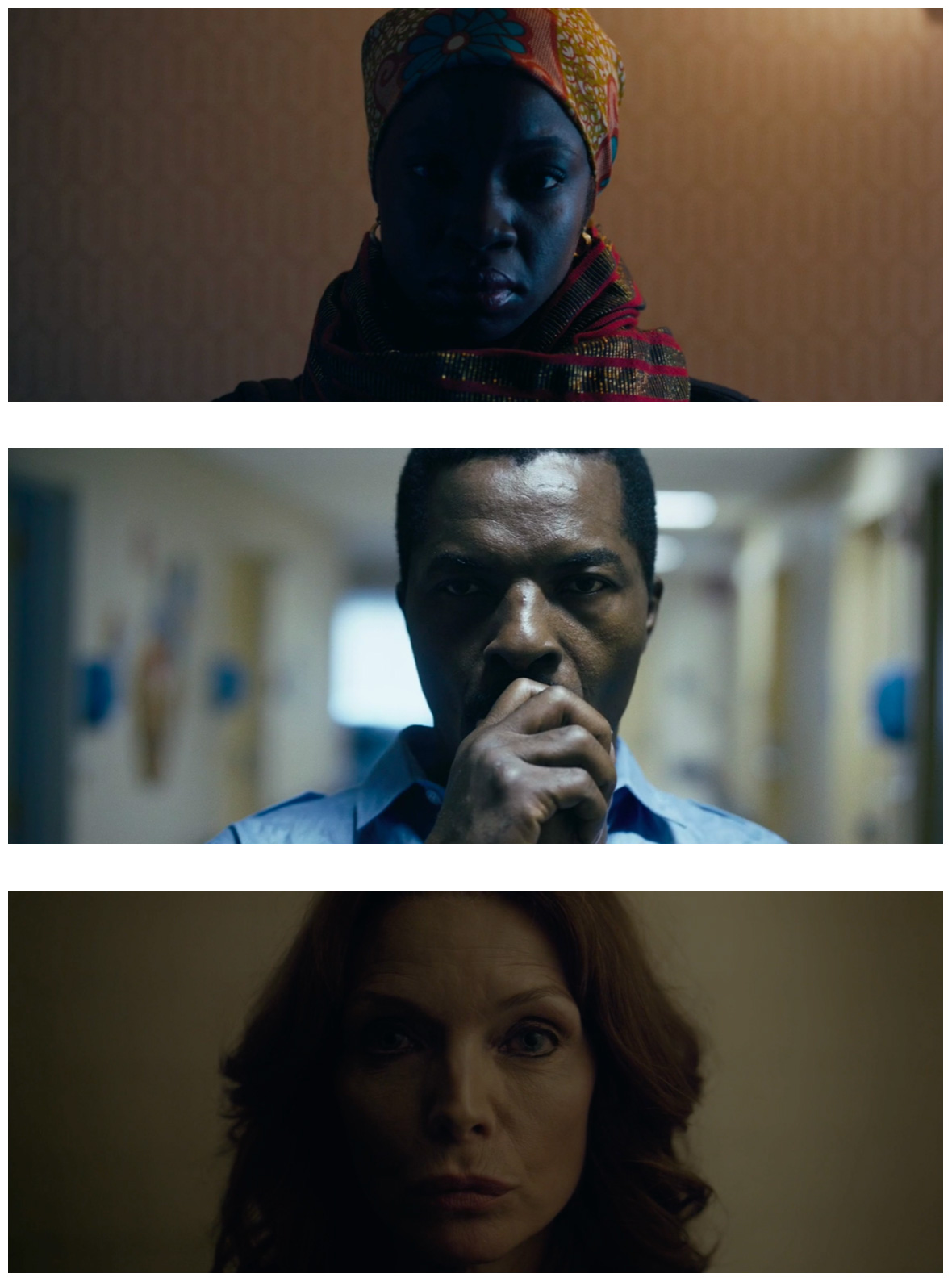

In a number of your films you have these moments where your camera lingers with an actor between scenes, and they look directly into the camera, or stand in front of the camera, as if for a portrait. Are these moments where you’re taking cinema back into the direction of photography?

That’s interesting. I think it’s coming from photography. My love for film — again, I’m very inspired by wondering, what’s behind that picture? You look at a portrait of Walker Evans’s and it’s this man on the street of Cuba. It’s just the head and shoulders, but there’s so much with that man that I want to know. There’s so much great photography — it’s so much about someone’s face that you just want to know what their life is about. What’s the scene prior to that? What’s the scene after that? Where do they live? What is their house like? I mean I try to create a world from someone’s face, from someone’s picture, and great portraiture does that. My lingering is almost like, there’s so much more I can tell you about this person. I want my audience to feel the same way. That’s why I’m trying to study this person. Take a minute. It’s not about listening to them, it’s not about their movement, but actually watch this person. Get to know them, just like a still photograph. You look at a Walker Evans portrait or you look at August Sander’s portraits, and it’s just a man sitting on a chair. But you understand that world. You understand the pain on someone’s face when you look at a Dorthea Lange picture. Or you look at a picture by Gordon Parks and it’s just a man sitting on his porch. But there’s so much more that that picture tells you. You don’t have to be in the South, you don’t have to be in Cuba with Walker Evans, but you understand that world, and that’s what I love about this portraiture. I hope to think that the audience actually senses the outer world, what is outside the frame. The hope is that the audience gets more of what’s outside the frame than what’s in the frame. I think that’s what great photography does.

That’s interesting. I think it’s coming from photography. My love for film — again, I’m very inspired by wondering, what’s behind that picture? You look at a portrait of Walker Evans’s and it’s this man on the street of Cuba. It’s just the head and shoulders, but there’s so much with that man that I want to know. There’s so much great photography — it’s so much about someone’s face that you just want to know what their life is about. What’s the scene prior to that? What’s the scene after that? Where do they live? What is their house like? I mean I try to create a world from someone’s face, from someone’s picture, and great portraiture does that. My lingering is almost like, there’s so much more I can tell you about this person. I want my audience to feel the same way. That’s why I’m trying to study this person. Take a minute. It’s not about listening to them, it’s not about their movement, but actually watch this person. Get to know them, just like a still photograph. You look at a Walker Evans portrait or you look at August Sander’s portraits, and it’s just a man sitting on a chair. But you understand that world. You understand the pain on someone’s face when you look at a Dorthea Lange picture. Or you look at a picture by Gordon Parks and it’s just a man sitting on his porch. But there’s so much more that that picture tells you. You don’t have to be in the South, you don’t have to be in Cuba with Walker Evans, but you understand that world, and that’s what I love about this portraiture. I hope to think that the audience actually senses the outer world, what is outside the frame. The hope is that the audience gets more of what’s outside the frame than what’s in the frame. I think that’s what great photography does.

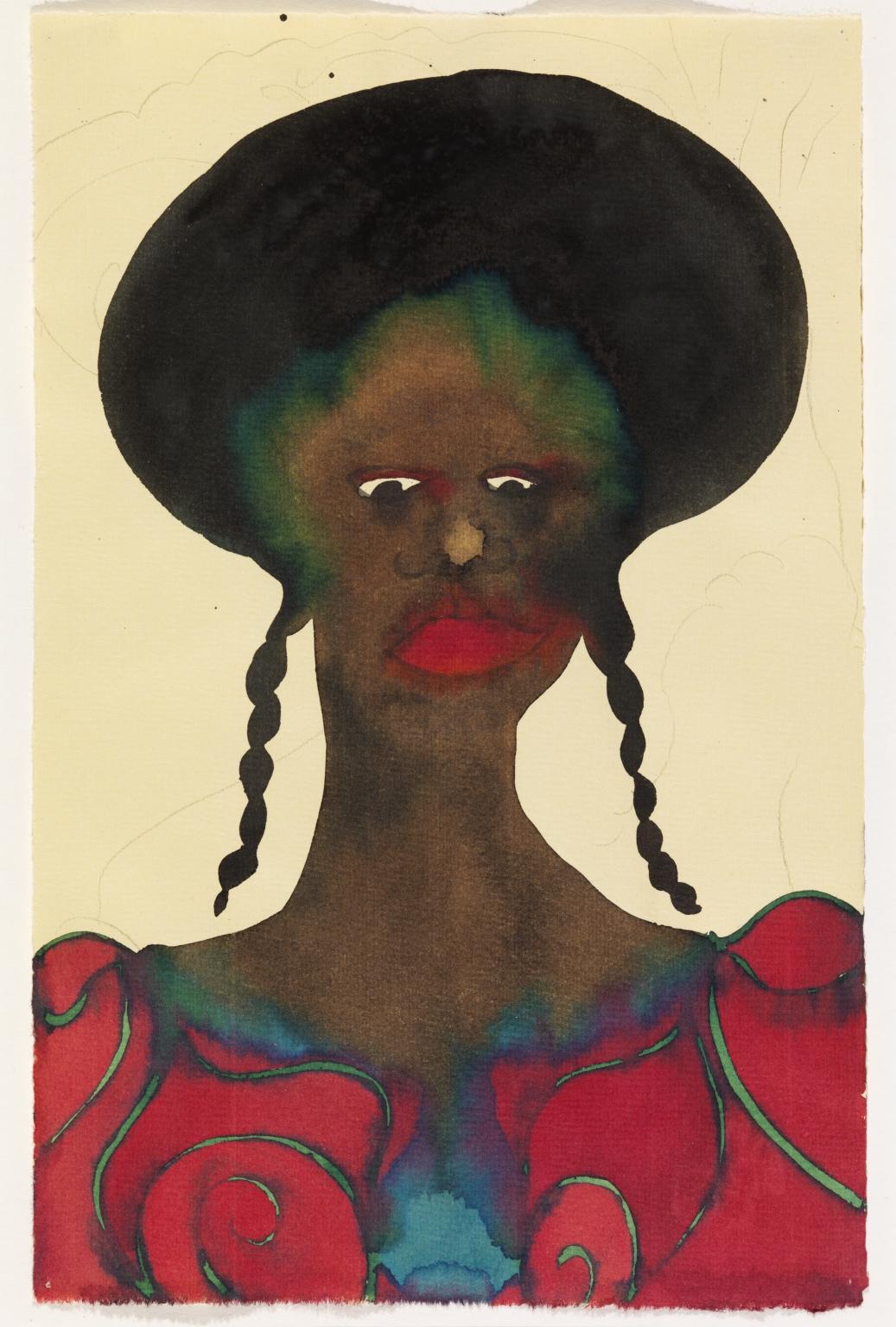

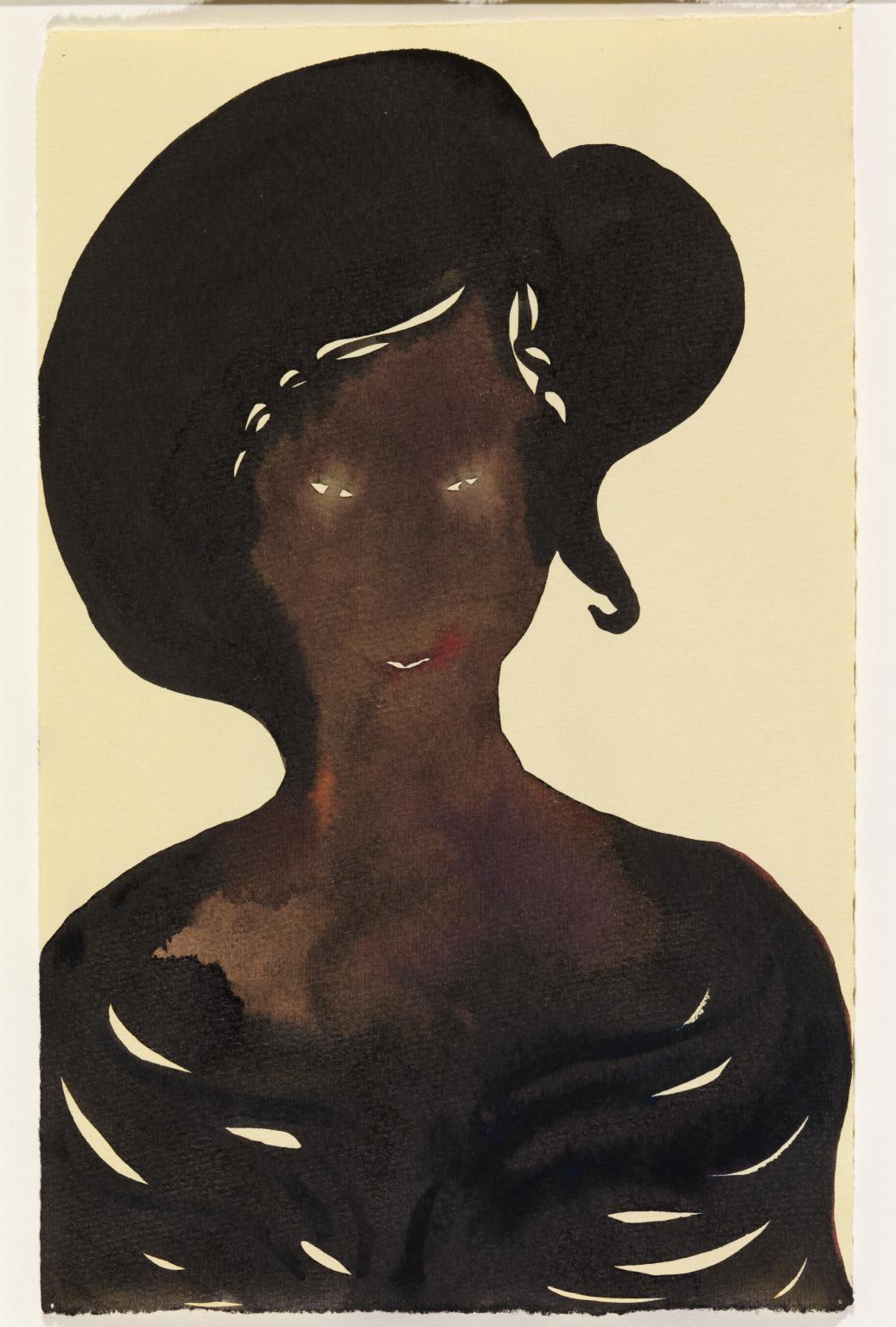

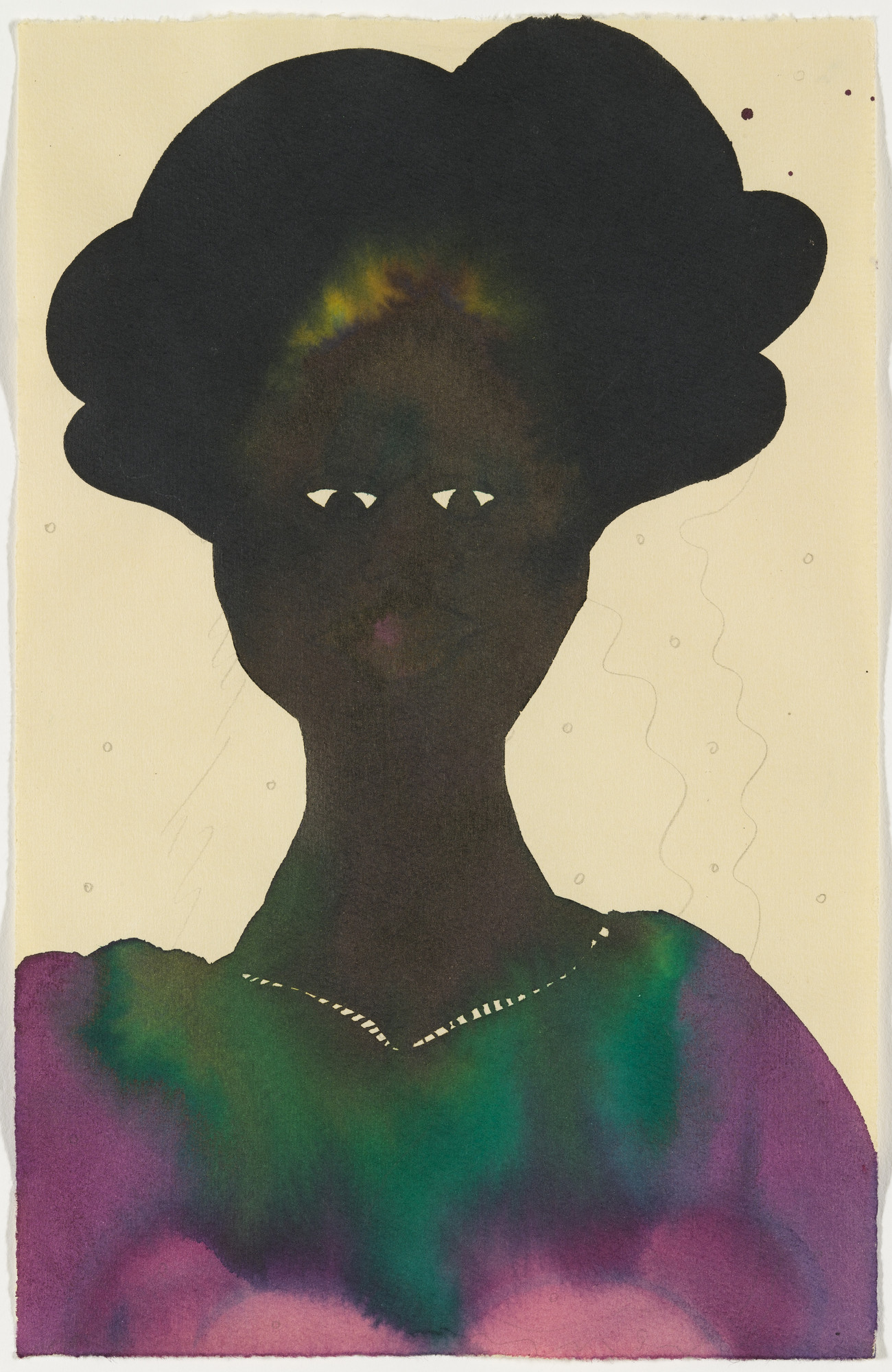

It’s interesting that you’re showing me these Chris Ofili pictures, because this series was such a big influence for me in the sense that, in most of my films, it’s a question of, “What is the skin texture?” Specifically in Mother of George, but in all of them, “What’s the skin texture?” One of the greatest things that ever revolutionized the art world is the mask, the African mask, you know? It’s an everyday object now, you can find a fake on every corner, but its introduction into the artworld revolutionized the artworld. What it does when it sits on the wall is what I want these portraits to do for the audience. You stop and look and there’s an aura. That’s why it was revolutionary. That’s what portraiture does for me, and the mask is something I reference every time: you walk into a room and you see a mask and you stop, and you look at it, and then you move on. But that moment of pause is what I try to create with my portraits on film.

In looking at these watercolors, you first mentioned skin texture. Are you thinking about how to render skin texture on film, or what did you have in mind?

Unfortunately in cinema … everything is just lit to be a certain kind. But I remember talking to Bradford and we were thinking about how you’re on the Continent, or anywhere in the South, and how Black individuals glow in the sun, you know? It’s the texture and the shine. I always think of a line of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, when she described the character Pecula. She was so lovely, her skin was so lovely, you almost felt that if you scratched it it would peel off in your hands. Literally that’s what I wanted it to feel like. If you scratched it it would come onto your hands. It was that beauty, for me personally, of seeing my grandma walking around. When I was making Mother of George I would think about the way she glowed.

In looking at these watercolors, you first mentioned skin texture. Are you thinking about how to render skin texture on film, or what did you have in mind?

Unfortunately in cinema … everything is just lit to be a certain kind. But I remember talking to Bradford and we were thinking about how you’re on the Continent, or anywhere in the South, and how Black individuals glow in the sun, you know? It’s the texture and the shine. I always think of a line of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, when she described the character Pecula. She was so lovely, her skin was so lovely, you almost felt that if you scratched it it would peel off in your hands. Literally that’s what I wanted it to feel like. If you scratched it it would come onto your hands. It was that beauty, for me personally, of seeing my grandma walking around. When I was making Mother of George I would think about the way she glowed.

It was that glow-ness that we were searching for. The glowness you saw when you saw a man walk through the streets of Dakar, and he’s wearing the brightest blue. On the notion of Indigo Blue, in the Tuareg culture, when you think of West Africa, you think of the essence and importance of blue, the indigo blue, the blue-black. It’s believed all across the desert, in the Sahara region of West Africa, to be beautiful is to be almost blue-black.

And on your wedding day, the Tuaregs make sure the bride wears blue and the blue has to be so dyed blue that it has to stain them. It’s a sign of beauty in the part of the region I come from. When you get married the wedding dress is in indigo blue, but the indigo blue has to be so raw to an extent that it has to stain you. That’s one of the references. It’s always been something for me, even in Restless City, when we see Djibril. That’s what we were going for with references as well. This celebration of Blackness.

I think Ofili was someone who touched on that, so it was a beautiful reference for us, because it touched on that conversation. The elegance, the colors, the beauty, and the celebration of it.

One other thing about Ofili’s portraits is that they’re made with watercolors. The hairlines, for example, are not marked by lines but are zones where one thing flows into another. Something similar happens in many shots we find in your films, for instance in the first shots of Restless City and Mother of George, where we see your main characters, big in the frame, walking in the city and going out-of-focus and dissolving into the space around them. Shots like this, that linger out-of-focus, have a quality of painterly abstraction, and we find them throughout your films. Can you talk about your interest in the out-of-focus?

And on your wedding day, the Tuaregs make sure the bride wears blue and the blue has to be so dyed blue that it has to stain them. It’s a sign of beauty in the part of the region I come from. When you get married the wedding dress is in indigo blue, but the indigo blue has to be so raw to an extent that it has to stain you. That’s one of the references. It’s always been something for me, even in Restless City, when we see Djibril. That’s what we were going for with references as well. This celebration of Blackness.

I think Ofili was someone who touched on that, so it was a beautiful reference for us, because it touched on that conversation. The elegance, the colors, the beauty, and the celebration of it.

One other thing about Ofili’s portraits is that they’re made with watercolors. The hairlines, for example, are not marked by lines but are zones where one thing flows into another. Something similar happens in many shots we find in your films, for instance in the first shots of Restless City and Mother of George, where we see your main characters, big in the frame, walking in the city and going out-of-focus and dissolving into the space around them. Shots like this, that linger out-of-focus, have a quality of painterly abstraction, and we find them throughout your films. Can you talk about your interest in the out-of-focus?

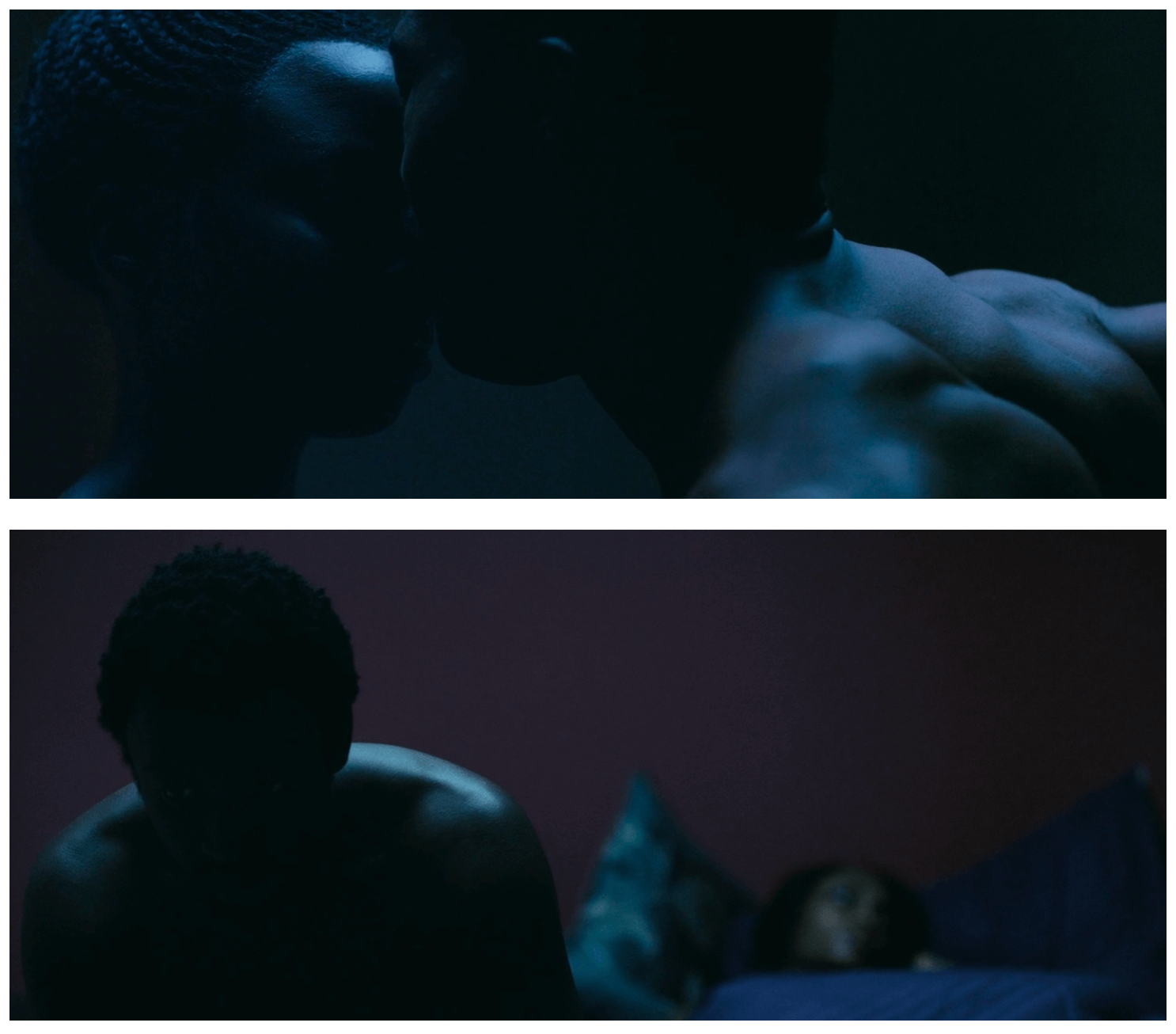

It’s interesting that you reference Chris’s paintings, because I’d actually like my films to feel like a watercolor painting, in the sense that not everything is defined. When you paint with a watercolor, the paint fades out. You get the outlines of things. That’s what I’d like my films to feel like, just the outline. Because you have an outline of a face and you have an eye, then you begin to imagine that the eye has got a nose and a mouth that we don’t necessarily have to see, but you know it’s there because you were able to create that outline. I think that’s what I try to do with focus as well.

It’s the sense of something. Creating that sense of something, so that for us, as an audience, we can suspend ourself into creating what we think that thing is. I really personally like to create my films to be like that. Figuratively, or visually, how do I not necessarily give you all the information? This is what a watercolor does, because it’s forced to fade out unless you dip it back into the paint. You know it’s a human being or a back of a dog, all you have to see is that shape. Not everything has to be in focus or drawn, and that’s my approach to filmmaking in general. How do I make us work as an audience — make us participants? You have to be puzzling, you have to be participating, you have to ask questions. I try to create that sense of an outline of something.

I think in every one of your films you include lingering shots of your subjects, portraits, in a way, taken from behind. It reminds me of Edward Yang’s Yi-Yi (2000), where there’s a young character who carries a camera around. He’s a photographer, and we wonder what he photographs. When we finally see his photos they’re all these portraits of people taken from behind. They’re amazing. In your films it feels like you’re observing textural details in these moments, but I wonder how you think of these shots?

It’s the sense of something. Creating that sense of something, so that for us, as an audience, we can suspend ourself into creating what we think that thing is. I really personally like to create my films to be like that. Figuratively, or visually, how do I not necessarily give you all the information? This is what a watercolor does, because it’s forced to fade out unless you dip it back into the paint. You know it’s a human being or a back of a dog, all you have to see is that shape. Not everything has to be in focus or drawn, and that’s my approach to filmmaking in general. How do I make us work as an audience — make us participants? You have to be puzzling, you have to be participating, you have to ask questions. I try to create that sense of an outline of something.

I think in every one of your films you include lingering shots of your subjects, portraits, in a way, taken from behind. It reminds me of Edward Yang’s Yi-Yi (2000), where there’s a young character who carries a camera around. He’s a photographer, and we wonder what he photographs. When we finally see his photos they’re all these portraits of people taken from behind. They’re amazing. In your films it feels like you’re observing textural details in these moments, but I wonder how you think of these shots?

There’s something that attracts me to that, because I’m a photographer and I’m constantly taking pictures. I’m taking pictures of people who are not even aware of them being taken pictures of. Most of my pictures are very detail-driven. And it’s a question of how to get the essence of what I want without them being knowledgable, because the minute they know, that beauty that I liked will change right away, because they’ll be conscious of it, and it will never be the same.

Yoruba culture, which is the part of society I’m from. This is probably one of the most advanced cultures when it comes to self-presentation, you know what I’m saying? These are people that have been wearing gold tooths and tattooeing their body for the past 5000 years. The scene from the Mother of George, that wedding scene, is a way that has been practiced for 5000 years. People did that.

It’s an old culture and aesthetically the Yoruba people are tribal marks, the whole notion of tribal marks and body tattooes was about creating a scene of beauty — gold teeth, indigo skin, these were beauty. There’s a culture of Yoruba people for whom that notion of beauty is a part of society. It’s them. The sense of dyeing your fingers. In modern society you wear fingernails. In this society you’d dip the tip of your fingers into indigo 5000 years ago. It’s the notion of that. It’s a world I met, not one I invented. It’s a world that is there and I just happened to put it on screen.

I remember one of the reasons I wanted to be a filmmaker — I remember being in France and watching all those films — is that I really wanted to depict my society, the richness of my society, and I think that’s what I got to do through Mother of George. The women I grew up with, that’s who they were.

Yoruba culture, which is the part of society I’m from. This is probably one of the most advanced cultures when it comes to self-presentation, you know what I’m saying? These are people that have been wearing gold tooths and tattooeing their body for the past 5000 years. The scene from the Mother of George, that wedding scene, is a way that has been practiced for 5000 years. People did that.

It’s an old culture and aesthetically the Yoruba people are tribal marks, the whole notion of tribal marks and body tattooes was about creating a scene of beauty — gold teeth, indigo skin, these were beauty. There’s a culture of Yoruba people for whom that notion of beauty is a part of society. It’s them. The sense of dyeing your fingers. In modern society you wear fingernails. In this society you’d dip the tip of your fingers into indigo 5000 years ago. It’s the notion of that. It’s a world I met, not one I invented. It’s a world that is there and I just happened to put it on screen.

I remember one of the reasons I wanted to be a filmmaker — I remember being in France and watching all those films — is that I really wanted to depict my society, the richness of my society, and I think that’s what I got to do through Mother of George. The women I grew up with, that’s who they were.

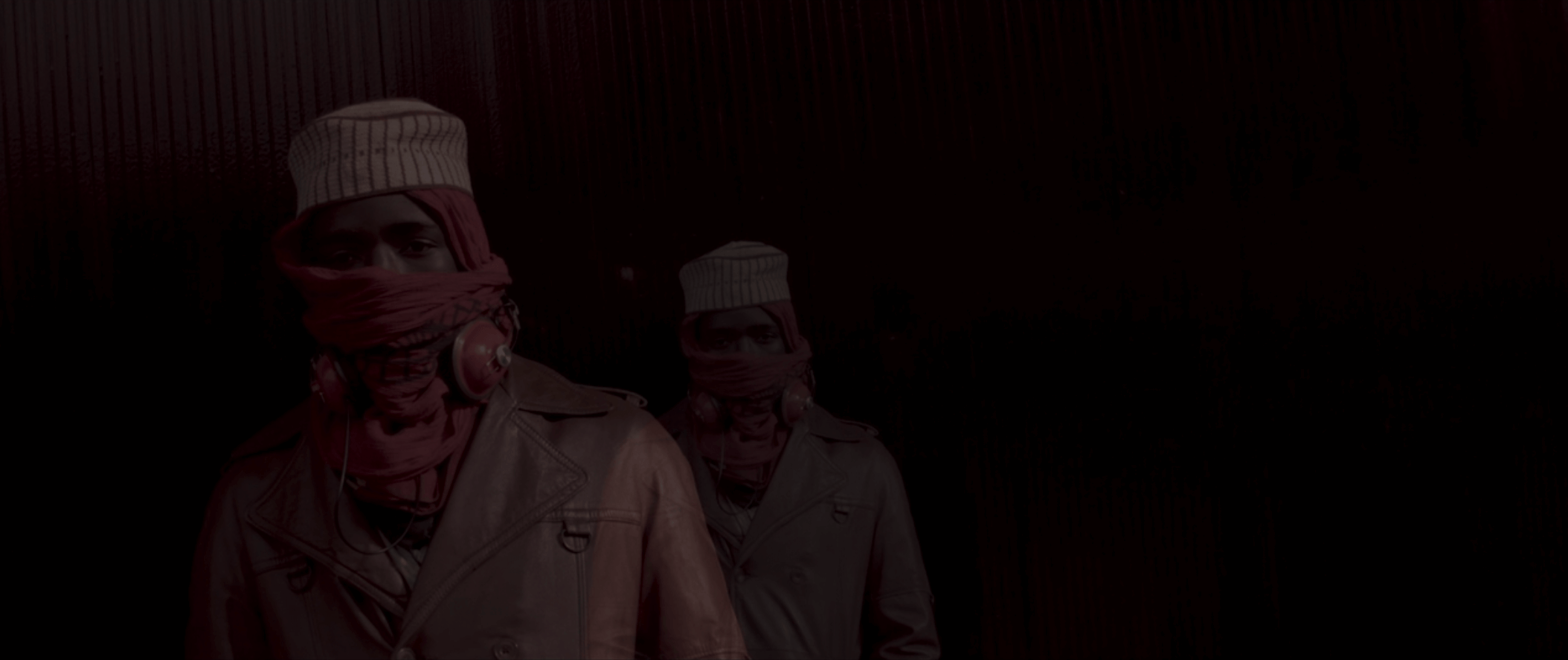

In your first feature, Restless City, you experiment with photography by superimposing shots to create a doubling of figures within the frame, or use reflections to layer images. Sometimes you shoot into the sun to explore lens flare as a graphic element. There’s a lot going in in this movie photographically.

![]()

![]()

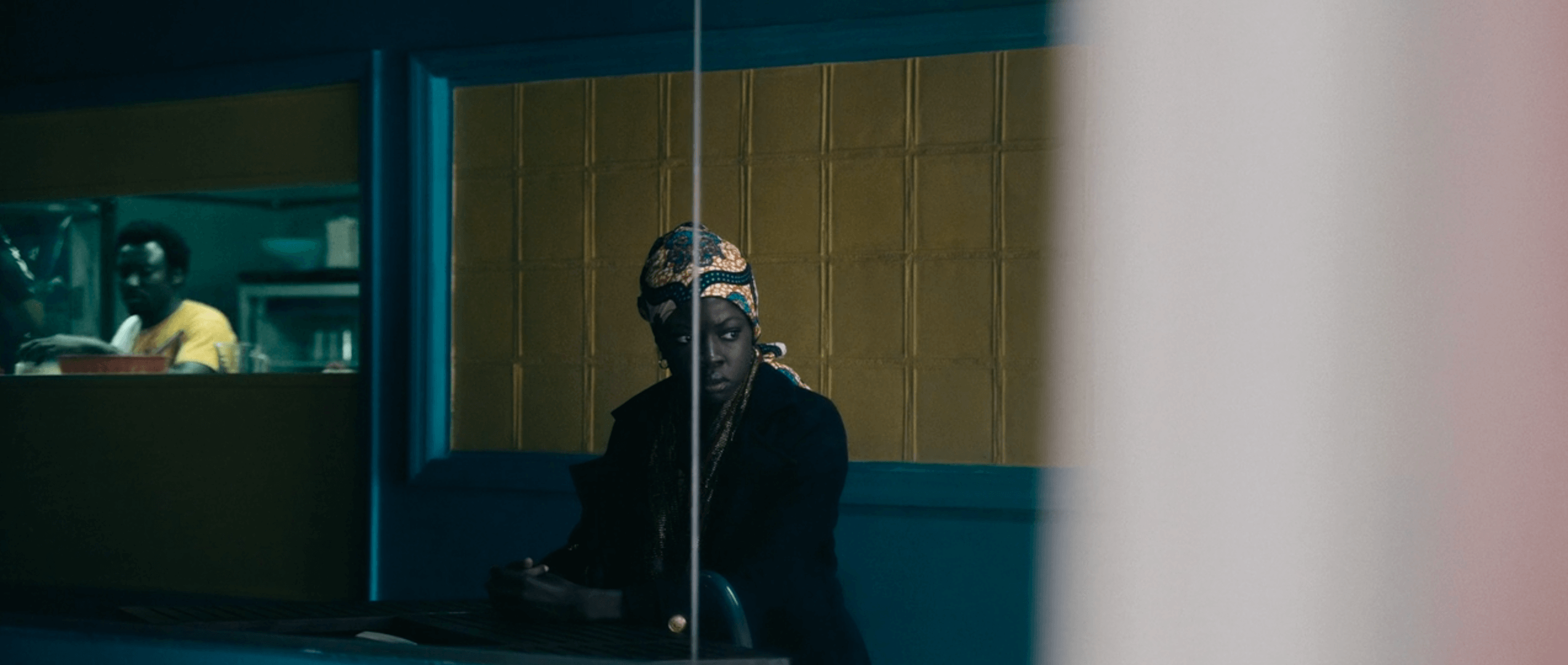

Then in Mother of George you’re exploring transparency and translucency, like when you shoot an important scene through a delicate fabric curtain, veiling the image. But Mother of George also uses mirrors and reflections in numerous shots, to multiply frames.

![]()

![]()

Then in Mother of George you’re exploring transparency and translucency, like when you shoot an important scene through a delicate fabric curtain, veiling the image. But Mother of George also uses mirrors and reflections in numerous shots, to multiply frames.

In Where is Kyra?, we often see frames within frames, too. In the films you’ve made with Bradford Young there’s an ongoing exploration of these different modalities of photography. You use these devices to tell emotional stories about characters, but you’re also using materials and strategies that seem to be reflexively about photography somehow.

Absolutely. I understand completely what you’re saying. That’s definitely a photographic influence. Being a photographer and studying photography to understand the power of images, to be able to do that, and to actually have a collaborator like Brad, where we both extend and work hand in hand to explore that some more. Having this free space as well. This was a film where we had free space, there was no studio or anything. Having all those freedoms to explore things where you don’t have some co-producer telling you “Why shoot in the mirror, go to the action.” But exploring it through photography — absolutely. I can tell you how much Walker Evans influenced this, all those Walker Evans pictures through mirrors. Or Robert Frank’s The Americans. They influenced me more than filmmakers do, absolutely.

I imagine people have asked you about the bathing scene in Where is Kyra?, when Kyra bathes her mother, and it’s shot in such a way that half the scene unfolds before there’s the surprising revelation that we’re looking into a mirror, when the door opens a little bit.

I can tell you’re a guy like me. Photography is such a big influence. When you were thinking about that shot, I was thinking about Larry Clark, and his photographs of the kids in Tulsa, shooting themselves in the bathroom. The door is slightly open.

Photography plays a big part for me as a storyteller. Because photography is the story. When I look at the pictures it’s the story in the pictures that fascinates me. I almost feel like the script is a blueprint. A lot of screenplay writers don’t like that, but it’s a blueprint. Everything else is equally important. My key teams are all one. We’re in a band. Whether it’s my production designer, costume designer, my DP. They’re all as equally important as me. I think directors often get it wrong. They think it’s their show. They’re the captain. I don’t see it that way. It’s our show. We’re in the band together, and we’ll play together. Let’s try, and if it fails, we’ll try something else. We equally have this canvas to paint on.

And what about the performers in front of the camera? Do you like to rehearse, or what’s your process like?

I do rehearse but not because I love to. There’s something you discover when rehearsing, but I would say there’s something confining and restrictive about rehearsal. Because you get an actor, bring them in, and everybody’s on their guard. There’s a kind of formalness to this controlled environment. So you have to take that away, and once you take that away, actors can expose themselves. That comes with comfort.

The big part of my work with actors is conversation. Taking them into that world. Going for a meal, sitting down somewhere, sitting in the park, and just talking it out. Talking about the world and the essence of that person. Who is this character? This character feels like somebody who could have been sitting down having a drink with August Wilson and they all vibe together. So you get into the head of that character. Just understanding that person. I personally prefer to just talk to my actors, to create conversations about what this person is like. What music do they listen to? That’s always so important to me. What shapes this character? Because when I can get you to understand what shapes them, then you can understand them. Part of my rehearsal process is being in conversation. Yes there’s a rehearsal, but equally important is the conversation. I’ll go have a drink with my actors and sit in a bar and just chat like you’re talking to your friend, and ask questions about the person. Who is this character? What are they like? What would they order to eat? Who would they like to flirt with? Trying to personalize it. All these little things that makes people who they are is what I’m interested in, so yes, conversation is a big part of my rehearsal process. Creating space for conversation so you can vibe. And when you have the vibe — everything is there.

That seems like a nice note to end on. Thank you so much for sharing these stories and talking about your work and creative process. And happy 10th anniversary to Mother of George!

Absolutely. I understand completely what you’re saying. That’s definitely a photographic influence. Being a photographer and studying photography to understand the power of images, to be able to do that, and to actually have a collaborator like Brad, where we both extend and work hand in hand to explore that some more. Having this free space as well. This was a film where we had free space, there was no studio or anything. Having all those freedoms to explore things where you don’t have some co-producer telling you “Why shoot in the mirror, go to the action.” But exploring it through photography — absolutely. I can tell you how much Walker Evans influenced this, all those Walker Evans pictures through mirrors. Or Robert Frank’s The Americans. They influenced me more than filmmakers do, absolutely.

I imagine people have asked you about the bathing scene in Where is Kyra?, when Kyra bathes her mother, and it’s shot in such a way that half the scene unfolds before there’s the surprising revelation that we’re looking into a mirror, when the door opens a little bit.

I can tell you’re a guy like me. Photography is such a big influence. When you were thinking about that shot, I was thinking about Larry Clark, and his photographs of the kids in Tulsa, shooting themselves in the bathroom. The door is slightly open.

Photography plays a big part for me as a storyteller. Because photography is the story. When I look at the pictures it’s the story in the pictures that fascinates me. I almost feel like the script is a blueprint. A lot of screenplay writers don’t like that, but it’s a blueprint. Everything else is equally important. My key teams are all one. We’re in a band. Whether it’s my production designer, costume designer, my DP. They’re all as equally important as me. I think directors often get it wrong. They think it’s their show. They’re the captain. I don’t see it that way. It’s our show. We’re in the band together, and we’ll play together. Let’s try, and if it fails, we’ll try something else. We equally have this canvas to paint on.

And what about the performers in front of the camera? Do you like to rehearse, or what’s your process like?

I do rehearse but not because I love to. There’s something you discover when rehearsing, but I would say there’s something confining and restrictive about rehearsal. Because you get an actor, bring them in, and everybody’s on their guard. There’s a kind of formalness to this controlled environment. So you have to take that away, and once you take that away, actors can expose themselves. That comes with comfort.

The big part of my work with actors is conversation. Taking them into that world. Going for a meal, sitting down somewhere, sitting in the park, and just talking it out. Talking about the world and the essence of that person. Who is this character? This character feels like somebody who could have been sitting down having a drink with August Wilson and they all vibe together. So you get into the head of that character. Just understanding that person. I personally prefer to just talk to my actors, to create conversations about what this person is like. What music do they listen to? That’s always so important to me. What shapes this character? Because when I can get you to understand what shapes them, then you can understand them. Part of my rehearsal process is being in conversation. Yes there’s a rehearsal, but equally important is the conversation. I’ll go have a drink with my actors and sit in a bar and just chat like you’re talking to your friend, and ask questions about the person. Who is this character? What are they like? What would they order to eat? Who would they like to flirt with? Trying to personalize it. All these little things that makes people who they are is what I’m interested in, so yes, conversation is a big part of my rehearsal process. Creating space for conversation so you can vibe. And when you have the vibe — everything is there.

That seems like a nice note to end on. Thank you so much for sharing these stories and talking about your work and creative process. And happy 10th anniversary to Mother of George!