Amy Heller

Canon Fodder

Well of course the canon of American letters has been contested previously, and if one considers The Autobiography of Malcolm X as an example, along with literature by such writers as Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison which has clearly made its way into the canon, one can ask whether the inclusion of oppositional writing has really made a difference. Has the canon itself been substantively transformed? It seems to me that struggles to contest bodies of literature are similar to the struggles for social change and social transformation. What we manage to do each time we win a victory is not so much to secure change once and for all, but rather to create new terrains for struggle.

—Angela Davis

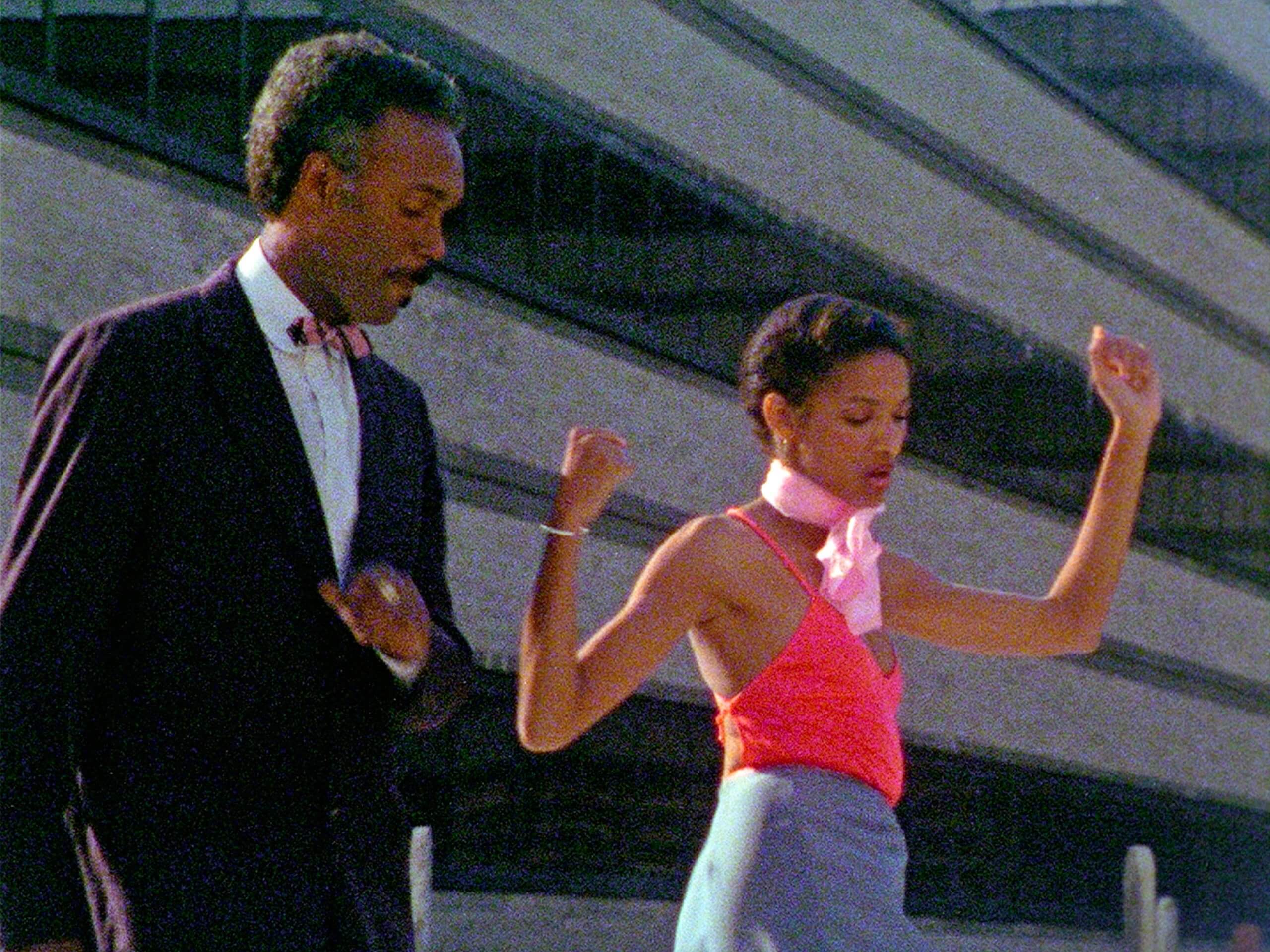

As co-founders (and the only staff) of Milestone Films, my husband Dennis Doros and I have, for the last three decades, made the decision to represent cinema of and by under-represented communities and filmmakers, including great films by African American filmmakers Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep and My Brother’s Wedding), Kathleen Collins (Losing Ground and The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy), and Billy Woodberry (Bless Their Little Hearts). We have released films that chronicle the lives of homeless people living on New York’s Bowery and Native American newcomers to Los Angeles. And we made it our mission to restore the film legacy of independent filmmaker Shirley Clarke. Several years ago Milestone brought out the great LGBTQ documentary Word is Out and we premiered restorations of four films by gay filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman at Lincoln Center in October 2020: Common Threads, Paragraph 175, The AIDS Show, and Where Are We?

As we put it: We like to fuck with the canon. But our company’s motto raises as many questions as it does eyebrows, and I would like to explore some of these questions here in the spirit of contributing to what Angela Davis described as new terrains for struggle in the quotation above.

Can we even hope to change or expand the accepted rosters of film masterpieces and great auteurs? Entrenched ideas and accepted norms (to say nothing of racism and misogyny) make mainstream movies the standard most people, critics, and even filmmakers accept. Looking at all of the Sight and Sound critics’ polls of the “Greatest Films of All Time” — going back to 1952 — I find that there has never been a film on the list directed by a woman or an African American in the Top Ten. The only nonwhite filmmakers in the polls are Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, and Kenji Mizoguchi. In 2012 the magazine polled filmmakers for their top 100 films: only one film directed by a woman made the list.

When the American Film Institute came up with its list of the 100 best American films not one was directed by an African American or a woman. And the AFI list also focused almost entirely on fiction features, leaving out documentaries, short films, and animation — film genres where women have historically been better represented.

Film production and distribution have long been controlled by a small cadre of (mostly) white (mostly) male studio executives. And increasingly, those execs are now employees of a handful of enormous multinational corporations. Film production in the United States is dominated by 20th Century Fox (owned by the Disney Corporation), Paramount Pictures (owned by ViacomCBS), Warner Bros. (owned by AT&T), Universal Pictures (owned by Comcast), Columbia Pictures (owned by Sony), and Walt Disney Studios (Disney again). Given the changing structure of the industry, we can add Netflix, Hulu (owned by Disney) and Amazon Prime.

(And of course, this industry structure and inherent biases are only the last step in the road to getting films made. Inequalities in education, policing, health care, income distribution, and well, everything, are insurmountable roadblocks for most people.)

Alas, we cannot look to film critics to remedy biases coming from the film production realm. In fact, we might have a hard time looking for film critics at all. There was a time when most cities and towns had newspapers with local film reviewers. Many of these (mostly male, mostly white) writers were enthusiastic cinephiles and their critiques could influence box office. Very, very few of these critics are still working in the field. We can lay responsibility for the change on the Internet and also on the consolidation of newspaper ownership.

Also … a canon fucked with is still a canon. Do we just want a different list of “greats?” Canons originally were designed to perpetuate religious tenets and to validate the importance of certain writers and writings. Those selections always did — and always will — reflect social, political, religious, and educational elites. Our literary canon includes William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens, but not Azerbijani poet Nizami Ganjavi, Senegalese writer Aminata Maïga Ka, or African American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar. And the same is true in our prevailing film canon.

Is it enough to add a selection of neglected films and filmmakers to the list and be done with it? How many do we need to add? What would those additions be? Can we add cellphone videos (some of which are changing history)? Should we include home movies? What about livestreams? When is the reimagined canon now acceptable? And when it is deemed appropriately inclusive and diverse, how do we ensure that it will grow in such a way that it reflects changes in the culture and the world?

So, maybe we could ask if we need a canon at all? If any list of “best” or “better” films and filmmakers is doomed to reflect the filmgoing experience, cultural biases, language skills, gender, and sexual orientation of critics, writers, programmers, and other cultural curators (like me!), do we want or need it?

I can say that I learned a lot about myself and my role as “cultural gatekeeper” (oy!) working on the release of Losing Ground. Back in 1985, when I first started working in independent film distribution in Manhattan, I was immersed in the world of independent film. This was just a few years after Kathleen Collins shot Losing Ground in and around New York City. In fact I knew one of Collins’s close friends, Jane Morrison (and my future husband Dennis actually stayed in Jane’s apartment when she was traveling in Africa). But I don’t think I ever even heard of Collins or Losing Ground. There were a lot of indie films getting attention in those years, but very few were made by African American directors.

When I first watched Losing Ground, decades later, I was initially a bit put off by the film’s occasional awkwardness and non-Hollywood look. Fortunately, Dennis and I were able to take time to watch and rewatch the film and we grew to appreciate and love its bold cinematography, brilliant writing, and powerful performances. But as the film’s distributor, I can say that Losing Ground has always been a very hard sell to art house theaters and to individual buyers. Now, thanks to the publication of Collins’s short stories and with the recognition of the importance of Black Lives Matter and its critique of American racism, there are more viewers discovering the film — but few, and so very late. Given the structure and ownership of the entertainment industry, I wonder how long this revived interest in African American filmmaking will last?

What if we decided to reject the idea of a canon? Or better yet, what if we embraced and explored the concept of many worlds of culture, creativity, images, and imagination? It can be hard to make those kinds of connections and explorations because the Internet tends to funnel us into narrow silos of interest, race, class, etc. So much of our online experience is shaped and exploited by some of the largest and most sinister corporations in the world. Remember when Google’s motto was “Don’t be evil?” They dropped it after dozens of employees resigned over the company’s refusal to cut ties to the US military. The practices of Facebook and its subsidiaries may well be undermining democracy in the US and around the world. We know that these entities want to sell us stuff and mine our data… and that both aims are used to separate us from one another. Too often we end up in virtual canyons, echoing and re-echoing our narrow community’s ideas of a canon…

We live in a world that is profoundly and powerfully connected and that has deep and important international roots and history. And there are amazing filmmakers, writers, storytellers, and people we already know who can help us challenge assumptions and see our shared reality in new and exciting ways. But to do so, we need to risk being uncomfortable. As newbies, we will sometimes ask dumb questions. But we also may make new friends we never expected. And we may see our worldview — and ourselves — grow.

Some of this work we may be able to do online… if we carefully avoid relying on social media. But we can also talk to friends and neighbors (wearing masks and social distancing, please). We can use our local libraries! We can write actual letters (and help save the US Postal Service). I treasure my pen pals around the world who help me connect and enlarge my horizons every day. Maybe try writing a note to an old friend or an online acquaintance? In fact, you can write to me and I will send you a letter or postcard back!

Here are a few sources of information that I have found and treasure… I hope other folks can share theirs!

Zinn Education Project

Artmattan Films

Gerald McWorter at the University of Illinois sends out amazing emails with resources on African American and Pan-African history and culture: abdulslist@lists.illinois.edu

The Center for Home Movies

Home Movie Day 2020

The Prelinger Library

The Public Domain Review

The Internet Archive

The Wayback Machine

Association of Moving Image Archivists

Women Film Pioneers Project

The epigraph is from Angela Y. Davis, Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005), p. 17.