Adam Piron

Pure Legend:

Dispatch from an Incomplete Search

for the DeMille Indians

----

A few years ago, I heard an outlandish story from my friend Adam Khalil. It was during my tenure as LACMA’s Film Curator and I was spending much time immersed in researching Hollywood’s Golden Age and the Indigenous image in American Cinema of that era. A scholar in his own right on the history of Indigeneity in the moving image, Khalil told me about a story he had read in Michelle H. Raheja’s Reservation Reelism about the DeMille Indians. He recounted that there had been a group of Native American performers, colloquially known as “Hollywood Indians,” who set out to petition the Bureau of Indian Affairs to form their own legally- and culturally-distinct tribe known as the “DeMille Indians.” My understanding at the time was that these performers had all acted in the films of Cecil B. DeMille, which was not totally accurate. According to Raheja’s book, DeMille himself had issued a number of commemorative pins to the members of this tribe who had used him as a namesake. What also struck me was that all of these performers were most likely based in Los Angeles at the time, given DeMille’s ties to Paramount and its lot, which also would’ve made for a seemingly undocumented chapter of Hollywood’s early history. All of these pieces created something like a planetary alignment of my interests and led me down a years-long, and still incomplete, rabbit hole of trying to uncover any and every detail that I could about this forgotten footnote of Hollywood history.

----

To understand the unique endeavor that the DeMille Indians proposed—to realize an actual tribal entity within what’s now known as the United States—one needs to understand what that actually means. It’s not like forming a society, business or a non-profit. It’s an arduous legal process that a tribal group or community must undertake before the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a department within the federal government, for a level of recognition as a separate government that’s both sovereign but at the same time subject to US law. Essentially, it’s setting up for a nation-to-nation relationship. There are a number of different requirements and vetting that such a group has to face, such as proof of a consistent tribal government over centuries, an established Indigenous language, culture, etc., which is what makes the idea of the DeMille Indians as a tribe such a radical idea. They were a collective of Indigenous artists identified solely by a shared history of their work in relation to the moving image. Their culture was their own image and its history within cinema itself.

----

A clue to tracking down the DeMille Indians lies in the very idea of the pins themselves. Unable to uncover any existing images of the pins, I was led down a path searching for any and all DeMille-related ephemera. This brought me to a series of promotional pins commissioned by DeMille to celebrate the release of his 1940 film Northwest Mounted Police. The film follows a Texas ranger, played by Gary Cooper, who rides north into Canada and helps the Mounties during the Riel Rebellion of 1885. The pins DeMille commissioned come in four variants: one of a Native American chief in profile, one of a brave in profile, another of a victorious Mountie holding a Native warrior in chains, and the last of a Texas Ranger also leading a warrior in chained bondage. Knowing what history has uncovered about DeMille's personal BDSM tastes brings an additional, discomforting layer to the already strikingly racialized images presented as promotional memorabilia. The film in question though is the only surviving link to anything related to the origins of the DeMille Indians.

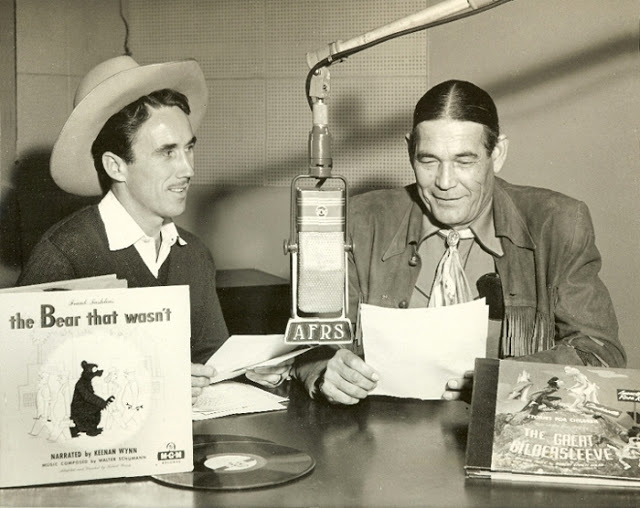

At this point I have to give a shout out to film critic Nick Pinkerton, who very generously let me use his newspapers.com account, which enabled me to track down a key story in the December 9th, 1940 issue of the Ames Daily Tribune of Ames, Iowa. The title reads: “DeMille’s Indians Are Back Again.” It’s a promotional interview for Cecil B. DeMille’s Northwest Mounted Police featuring one of its performers, Chief Thundercloud. It reads:

“There are only a few of us real Indians working in the film industry,” he notified DeMille by letter. “Some of us frequently can’t get work, although there are plenty of Indian roles in pictures. Half the time the players who are supposed to be Indians are Mexicans or Fillipinos or white men made up to look like Indians.

“But you always use real Indians in your pictures.”

“Right now, I am organizing the real Indians of Hollywood into a social club, and out of tribute to you we are going to call ourselves the ‘DeMille Indians,’ because you have made that name almost as famous as the real tribes. We think it is time there was an actual ‘DeMille’ tribe and we are going to be it.”

According to an earlier article in the New York Herald Tribune on November 17th of that same year, Thundercloud and a group of eighteen other unnamed members of the DeMille Indians’ were in the process of applying to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to be recognized as a legal tribe under the American government. The DeMille Indians or their endeavors beyond the end of 1940 are unknown.

----

In the Spring of 2020, a major clue to this mystery came my way. After tweeting about some of my research about the group, filmmaker Joe Peeler had reached out to me with a lead that he knew of. Peeler was making a film on the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and pointed me in the direction of the son of his subject: Professor Jacob Floyd, an Assistant Professor in Visual Studies at the University of Missouri who had connected with the family of an actor who had been a member of the DeMille Indians. This family had one of the DeMille pins in their possession.

It was around roughly a year later that I circled back to Floyd. Once we were able to find a time to connect, he was incredibly generous with his time and findings in his research. Similarly, he had run into a number of dead ends in terms of his own search for more information on the DeMille Indians, but he had found some key pieces. While Floyd did not have an image of the DeMille pin itself, the family had shared an image of it with him. He recounted some of the details with me, namely that it had the stereotypical profile of a Native American within it and text inlaid that said something along the lines of “DeMille Celebrates First Americans on Screen.” He also informed me that the performer who had owned the pin appeared in films under the screen name of Chief Rolling Cloud. Rolling Cloud, née Charles Brunner, had been a member of Floyd’s own tribe of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma. He found steady work throughout the 1940’s and into the 1950’s in B-pictures, as well as larger studio fare such as Nicholas Ray’s The Flying Leathernecks (1951) and Budd Boetticher’s Seminole (1953). Like many Native performers of the time, his title of chief was a concoction of studio publicity in order to sell an idea and image of authentic Indigeneity as a selling point for films being promoted. Brunner also ran with a crowd of Native (and some later to be relieved, non-Native) performers of the time who got similar gigs from straddling studio productions, B-Westerns and serials that included the likes of: Jay Silverheels, Chief John Big Tree, George Sky Eagle, Chief Many Treaties, Chief Yowlachie, Chief Thundercloud, Iron Eyes Cody and Chris Willow Bird.

According to Floyd’s research for a forthcoming book on Indigenous performers of the era (the projected publication date is in 2024 for the University of Nebraska Press), Hollywood of the 1920s–1940s created a melting pot of Native performers, many arriving in Los Angeles because of the production boom brought on by Westerns. They took on roles as on-screen actors, extras, stunt people and cultural consultants. A major gathering place for many of them was the American Indian Art Shop on Hollywood Boulevard, across the street from Grauman’s Chinese Theater. Originally founded by performers Chief Yowlachie (née Daniel Simmons) and his wife White Bird (Mary Simmons), this shop provided a hub for performers to sell their wares, as well as a space for cultural gatherings and a place for advocacy groups to meet, such as the War Paint Club: an organization meant to protect the rights of Native American actors and to discourage non-Native actors from playing Native roles. It is unclear whether the DeMille Indians were directly affiliated with the American Indian Art Shop or the War Paint Club, but these performers occupied the same space and shared the same concerns in an era that saw Indigenous performers demanding increased agency, better working conditions, and more accurate representations on screen.

----

One of the great ironies of the DeMille Indians lies with Chief Thundercloud himself. It was later revealed that this seemingly de facto spokesperson for the group was not even Indigenous at all. He was a charlatan. Born Victor Daniels in the then-territory of Arizona, he had falsely claimed that he was from Oklahoma and alternated between identifying as either Cherokee or a descendant of the Muscogee aristocracy, of which there has never been such a thing. He continued to play Native roles and went to his grave denying the accusations and the proof surrounding his appropriated identity. After a series of legal troubles, he spent his final years performing in live western shows at the Corriganville Movie Ranch in Simi Valley for tourists before eventually succumbing to stomach cancer at the age of 56 in 1955. His final screen appearance was in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), released shortly after his passing.

----

After looking through the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ archive of petitions for tribal recognition, there’s no record or even a mention of the DeMille Indians, Cecil B., nor Chief Thundercloud. It’s a dead end and an indication of what both Floyd and I have come to suspect. In all likelihood, the formation of the DeMille Indians into an actual, legal tribe was most probably the creation of the Paramount Pictures publicity machine. Much like the chieftain titles contrived for performers, this was likely another attempt to sell an audience an idea of indigeneity, or at least a performance of it. Still, the pins themselves existed and Brunner’s own involvement indicates that there were actual Native performers involved in this endeavor. What did they think of all of this? Was it all promotional showmanship or was it also something else? Why mention the Bureau of Indian Affairs when such a specific legal process would likely have simply gone over the heads of the 99% of non-Native audiences? At this point, there are more unknowns and dead ends than there are surviving fragments of the truth. Much like Westerns themselves, the DeMille Indians are pure legend.

In part, you could say that the DeMille Indians would not have existed, even as an idea, were it not for Westerns. The need for the Indigenous image in these films spurred many of these Native performers to heed the call from productions looking for stoic villains, scouts, warrior extras, and behind-the-scenes cultural consultants. It was steady work that paid better than what they could find at home. Many found something like a home among their own in the backlot camps of Inceville early on, and later at the aforementioned American Indian Art Shop. Being away from one’s tribal community was a new identity and a grey area that many of these Native performers had to navigate. This dynamic created something of a double-edged sword for Native performers negotiating both their place and image within the larger Hollywood machine. Much like the idea of the DeMille Indians themselves, it brings up the question of who gets to determine what is and what isn’t the Indigenous image.

Admittedly, even knowing that the proposal of such a tribe was probably nothing else but a joke to hype a DeMille film (of all things), it’s created something of a feedback loop in my head that I haven’t been able to escape. There’s an apocryphal beauty to all of it. It provokes questions around how we as Indigenous people can define ourselves and what our sovereignty can mean when we affirm it beyond the dynamics set forth by the terms and conditions of our settler colonial states. Coupled with cinema, it also presents a radical notion: inverting the concept of a national cinema by forming an actual nation shaped by a history to the moving image. It’s an ouroboros of self-determination, control and cinema’s power; a cycle of death and rebirth. The DeMille Indians may have not been an answer to anything, let alone film’s exploitation of Indigenous people, but in ways they’re something like a starting point.

Adam Piron is a filmmaker based in Southern California. He's a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, a Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (Mohawk) descendant and was raised in Phoenix, Arizona. His films have played in The New Yorker's Documentary Series, True/False Film Festival, San Francisco International Film Festival, MoMA Doc Fortnight, Camden International Film Festival, Indie Grits and various other festivals.

He is also a co-founder of COUSIN, a collective supporting Indigenous artists expanding the form of film. He currently works as the Associate Director of Sundance Institute's Indigenous Program.

Contributors: Jacob Floyd