100 Years of NOSFERATU

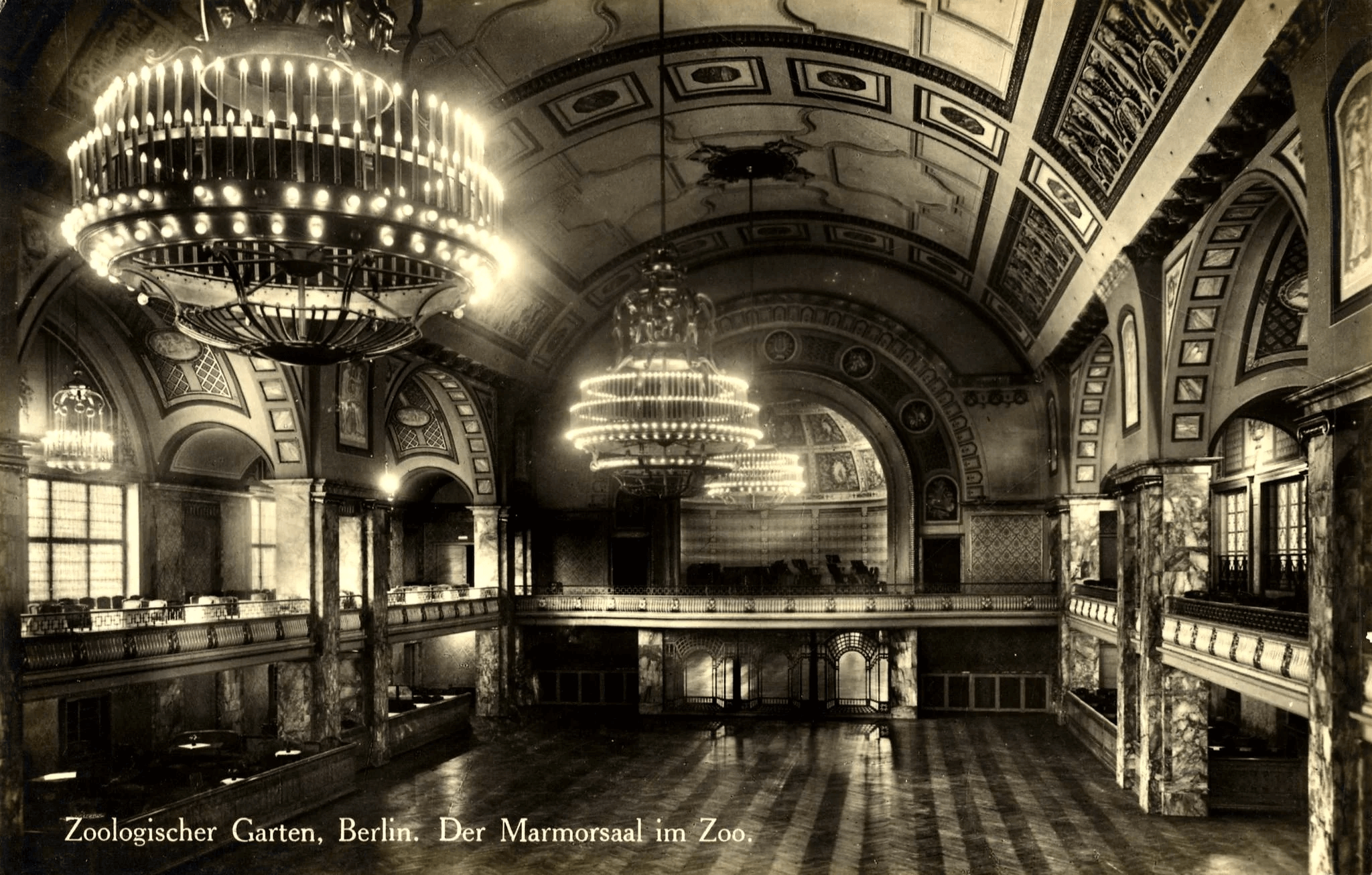

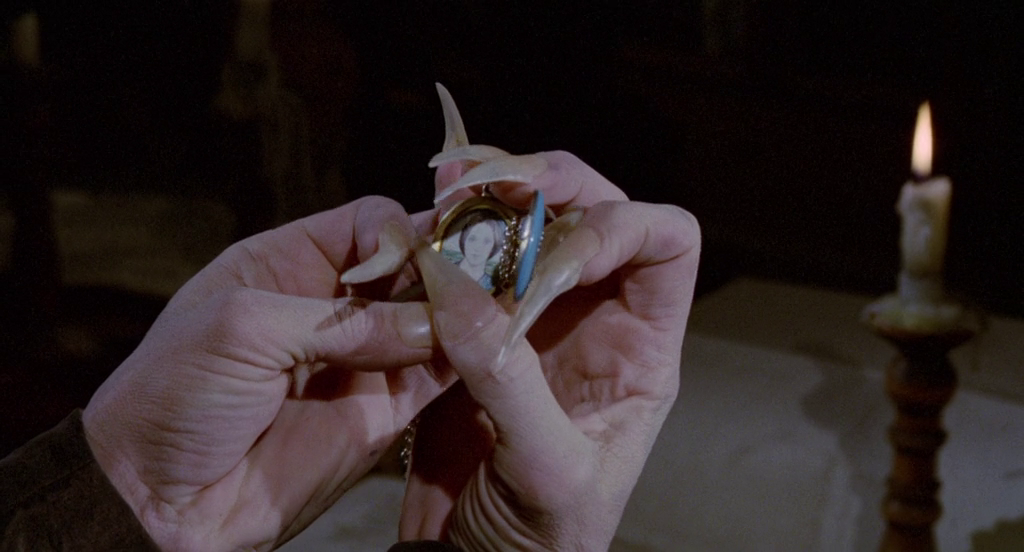

The movie Nosferatu premiered on March 4, 1922 in the spectacular Marbel Hall of the Berlin Zoological Garden. The event was planned as an elaborate society evening called Das Fest des Nosferatu (The Festival of Nosferatu), and guests were asked to arrive dressed in Biedermeier costume to coordinate with the film’s 1838 historical setting.

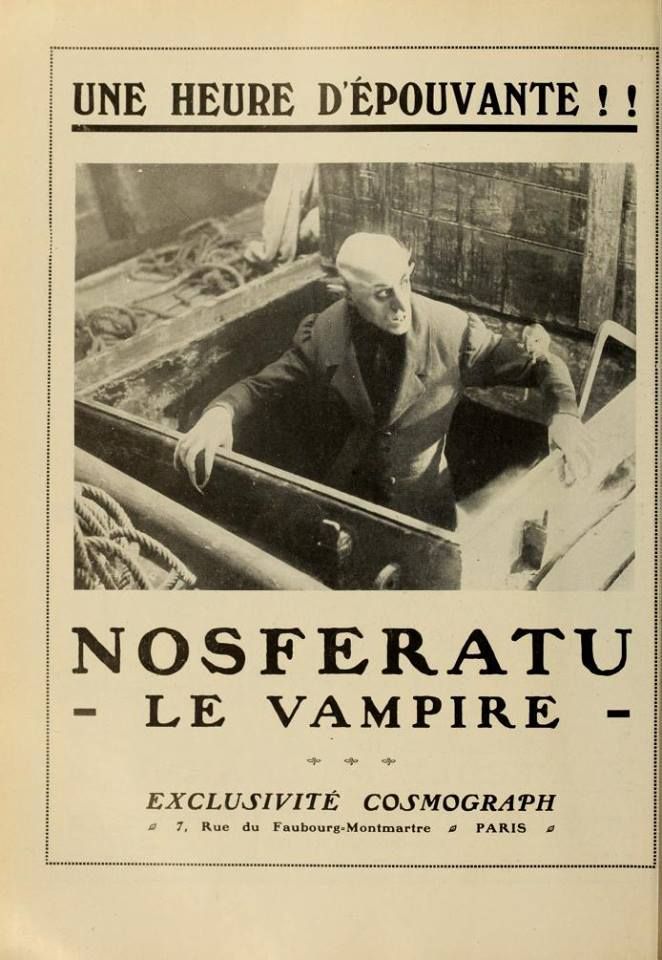

As the first feature-length vampire movie, Nosferatu, loosely adapted from Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, is notorious for its legal troubles. Prana Film, the production company formed to make the film, did not get copyright permission from the Stoker estate. They went bankrupt almost immediately.

![]()

Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker’s widow (once courted by Oscar Wilde), was living in London when she saw a program announcing the premiere of Nosferatu as an adaptation of Dracula. Stoker sued the company that took over Prana Film for copyright infringement. After meandering litigation, she ultimately requested that all surviving prints and negatives of Nosferatu be destroyed, and a German court ruled in her favor. By this point prints were in distribution, and the Nosferatu that survives today is a Frankenstein assemblage from a variety of prints and fragments.

100 years after its premiere, this masterpiece of Weimar cinema remains one of the most iconic films ever made and continues to influence new generations of artists and filmmakers. This December the Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg museum in Berlin will host Phantoms of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu, and here below, curators Jürgen Müller, Frank Schmidt, and Kyllikki Zacharias discuss their approach to the project.

As the first feature-length vampire movie, Nosferatu, loosely adapted from Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, is notorious for its legal troubles. Prana Film, the production company formed to make the film, did not get copyright permission from the Stoker estate. They went bankrupt almost immediately.

Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker’s widow (once courted by Oscar Wilde), was living in London when she saw a program announcing the premiere of Nosferatu as an adaptation of Dracula. Stoker sued the company that took over Prana Film for copyright infringement. After meandering litigation, she ultimately requested that all surviving prints and negatives of Nosferatu be destroyed, and a German court ruled in her favor. By this point prints were in distribution, and the Nosferatu that survives today is a Frankenstein assemblage from a variety of prints and fragments.

100 years after its premiere, this masterpiece of Weimar cinema remains one of the most iconic films ever made and continues to influence new generations of artists and filmmakers. This December the Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg museum in Berlin will host Phantoms of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu, and here below, curators Jürgen Müller, Frank Schmidt, and Kyllikki Zacharias discuss their approach to the project.

What does the word “Nosferatu” mean?

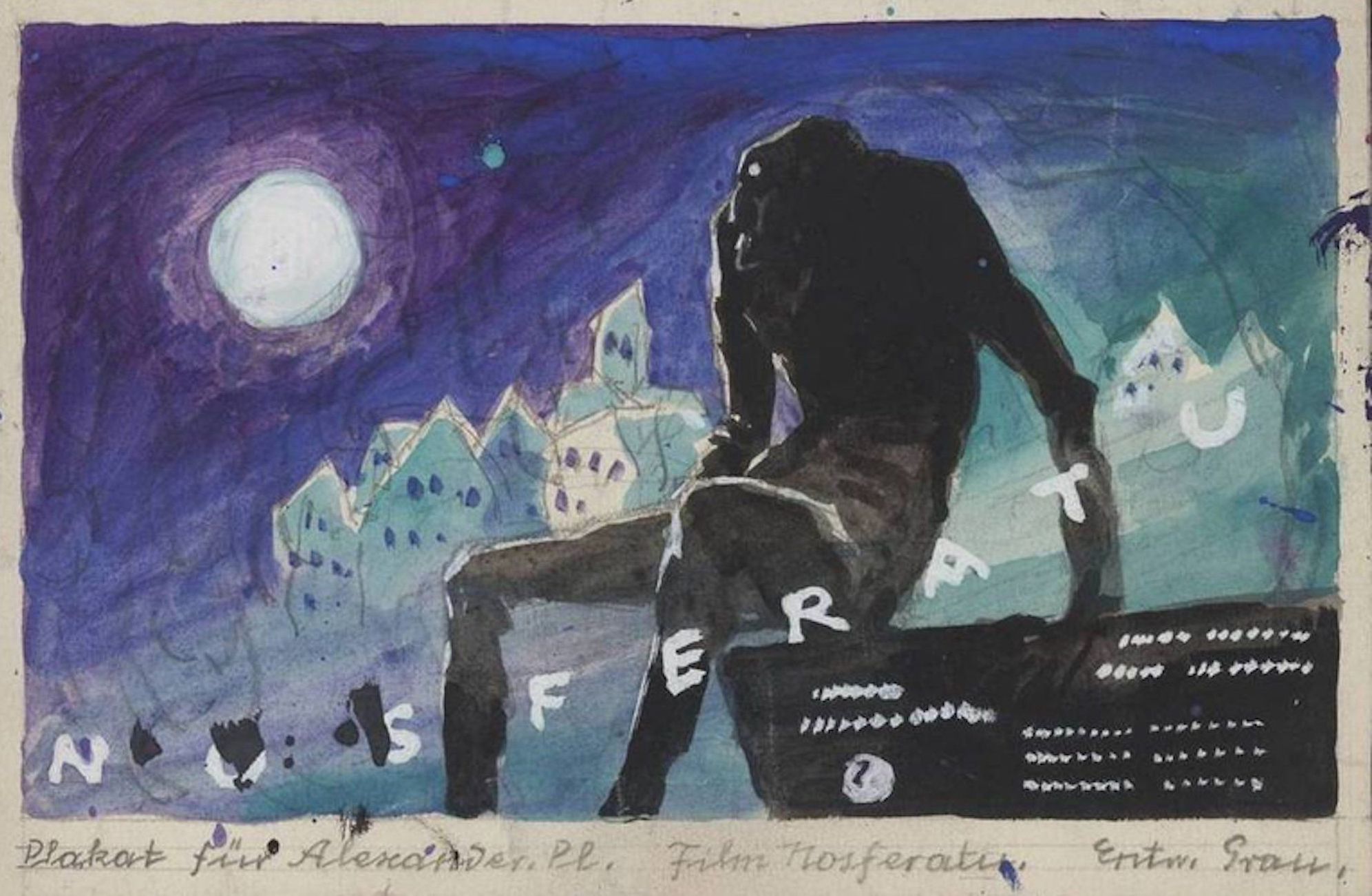

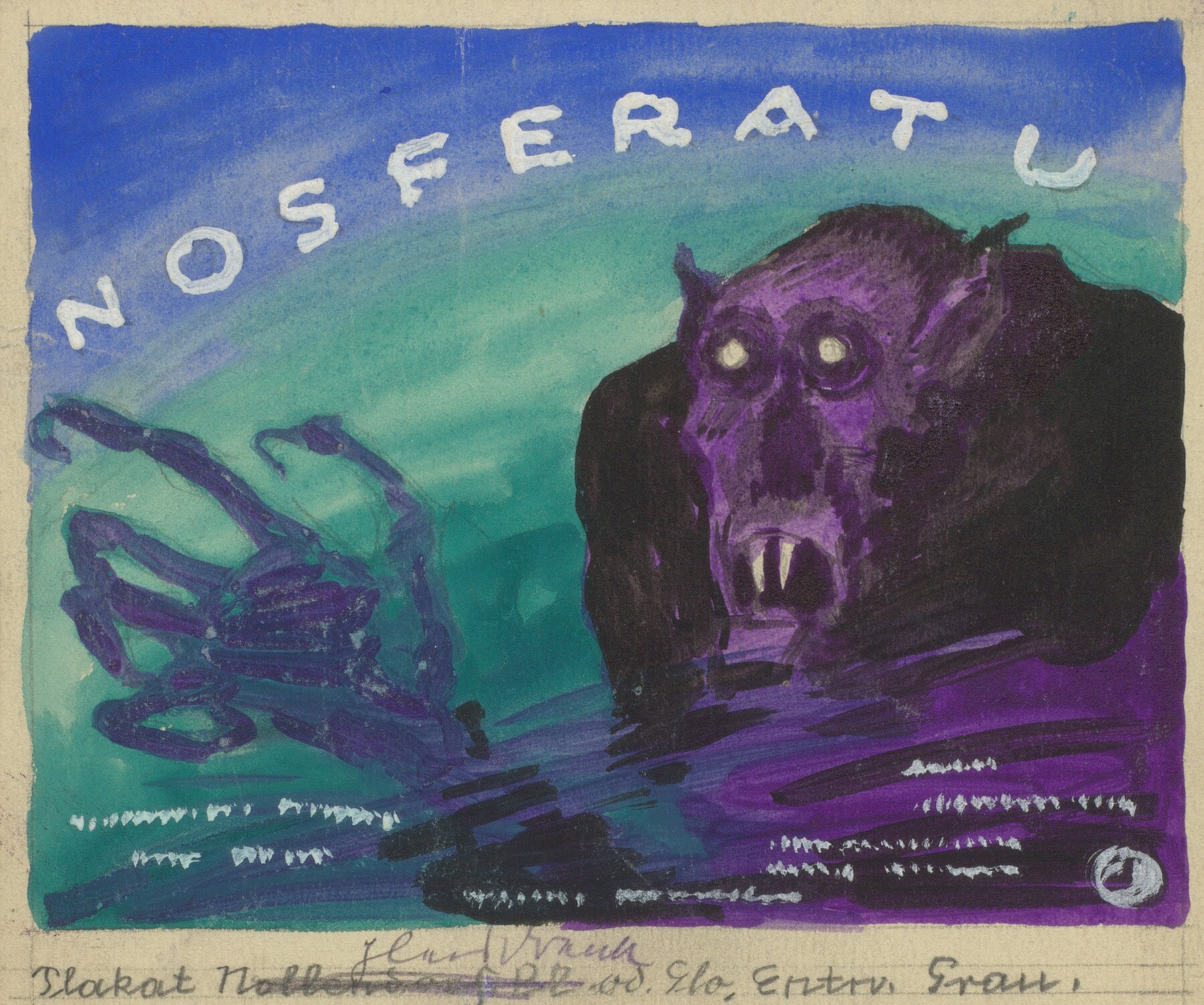

Jürgen Müller: It is a Romanian word meaning “the undead.” It appears in Bram Stoker's Dracula, so I assume [Nosferatu screenwriter] Henrik Galeen, who spoke excellent English, got to know it there. The strangeness of the word is emphasized in the advertising campaign designed by Albin Grau.

Jürgen Müller: It is a Romanian word meaning “the undead.” It appears in Bram Stoker's Dracula, so I assume [Nosferatu screenwriter] Henrik Galeen, who spoke excellent English, got to know it there. The strangeness of the word is emphasized in the advertising campaign designed by Albin Grau.

Nosferatu was directed by F.W. Murnau, one of the legends of silent cinema. But who was Albin Grau? He is listed as a producer and credited as designing the costumes and the sets. He also designed the posters for the film, so he was very involved in this iconic movie. He is also remembered as an occultist, but I’m not sure what that meant in practice. What should we know about Albin Grau and his role in Nosferatu?

Frank Schmidt: Leipzig-born Albin Grau was an avowed occultist who also met Aleister Crowley in the mid-1920s. But artistic works and the literature in his estate reveal that his esoteric interests were definitely broader. We try to reflect this in the exhibition.

Grau tried to increase his own reputation by claiming to have studied at the Dresden Art Academy, but there is no evidence of this. His business card designs from that time show Grau as a painter and advertising artist (“Maler und Werbezeichner”). Our exhibition will include advertising designs that he created for department stores.

When one considers Grau’s extensive involvement in the making of Nosferatu, it becomes clear that his role went far beyond that of a normal producer. Indeed, he designed buildings for Nosferatu (the surviving sketches show exactly how these were realized).

In addition to the advertising campaign he conceived, he placed numerous articles in film magazines, one of which tried to position Nosferatu as a “film of the intellectuals.” In retrospect, he thus appears, along with Henrik Galeen and Murnau, as one of the central creative figures behind the film.

You’re currently co-curating an exhibition called Phantoms of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu, which will open in Berlin this December. What was your starting point for this project? Was there a first research question, artifact, or theme that guided your initial approach?

Frank Schmidt: The original idea for the exhibition goes back to Jürgen Müller and his long-standing interest in Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, to whose work he has dedicated several essays. The centenary of Nosferatu offered the opportunity to deepen this interest together and to document comprehensively the relationship Nosferatu had to the fantastic art and literature of the time. Kyllikki Zacharias, the head of the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection, is an expert on surrealism and was immediately enthusiastic when it came to collaborating on this exhibition by hosting Phantoms of the Night. 100 Years of Nosferatu in the museum.

From my personal point of view, Nosferatu was – as I’m sure it is for many film viewers – always a film that, despite its age, still exerts an immense fascination and always stayed in my mind after the first viewing. This has to do with the figure of Count Orlok, of course, but also with the cinematic elaboration of the irrational. The juxtaposition of antithetical dynamics, which is so fundamental to the effect of Nosferatu, is something we still encounter in many horror films today, which is why, in addition to the fantastic art that influenced the film, I also wanted to look at the effect of Murnau’s film on other artists and filmmakers and their different approaches.

Frank Schmidt: Leipzig-born Albin Grau was an avowed occultist who also met Aleister Crowley in the mid-1920s. But artistic works and the literature in his estate reveal that his esoteric interests were definitely broader. We try to reflect this in the exhibition.

Grau tried to increase his own reputation by claiming to have studied at the Dresden Art Academy, but there is no evidence of this. His business card designs from that time show Grau as a painter and advertising artist (“Maler und Werbezeichner”). Our exhibition will include advertising designs that he created for department stores.

When one considers Grau’s extensive involvement in the making of Nosferatu, it becomes clear that his role went far beyond that of a normal producer. Indeed, he designed buildings for Nosferatu (the surviving sketches show exactly how these were realized).

In addition to the advertising campaign he conceived, he placed numerous articles in film magazines, one of which tried to position Nosferatu as a “film of the intellectuals.” In retrospect, he thus appears, along with Henrik Galeen and Murnau, as one of the central creative figures behind the film.

You’re currently co-curating an exhibition called Phantoms of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu, which will open in Berlin this December. What was your starting point for this project? Was there a first research question, artifact, or theme that guided your initial approach?

Frank Schmidt: The original idea for the exhibition goes back to Jürgen Müller and his long-standing interest in Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, to whose work he has dedicated several essays. The centenary of Nosferatu offered the opportunity to deepen this interest together and to document comprehensively the relationship Nosferatu had to the fantastic art and literature of the time. Kyllikki Zacharias, the head of the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection, is an expert on surrealism and was immediately enthusiastic when it came to collaborating on this exhibition by hosting Phantoms of the Night. 100 Years of Nosferatu in the museum.

From my personal point of view, Nosferatu was – as I’m sure it is for many film viewers – always a film that, despite its age, still exerts an immense fascination and always stayed in my mind after the first viewing. This has to do with the figure of Count Orlok, of course, but also with the cinematic elaboration of the irrational. The juxtaposition of antithetical dynamics, which is so fundamental to the effect of Nosferatu, is something we still encounter in many horror films today, which is why, in addition to the fantastic art that influenced the film, I also wanted to look at the effect of Murnau’s film on other artists and filmmakers and their different approaches.

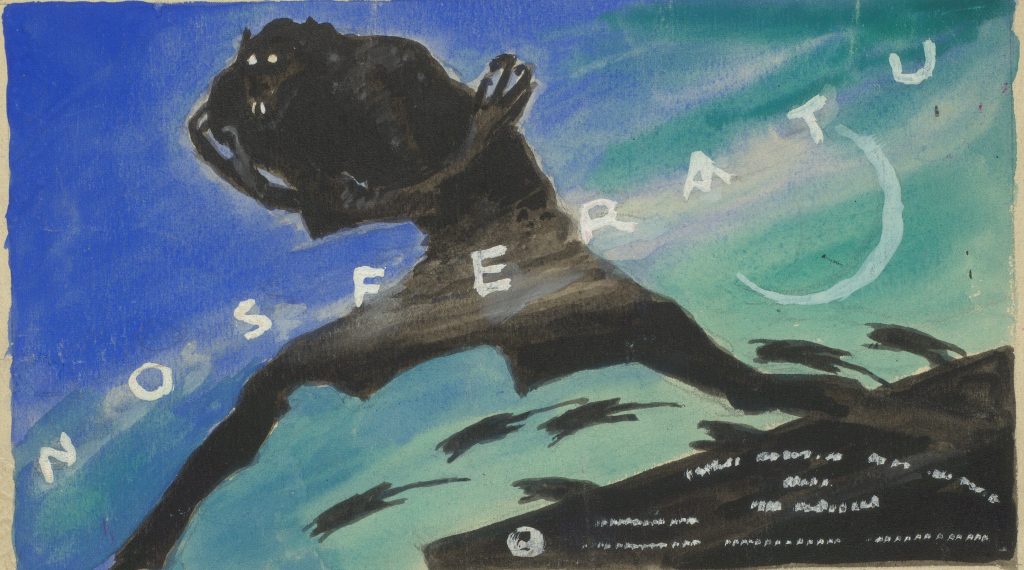

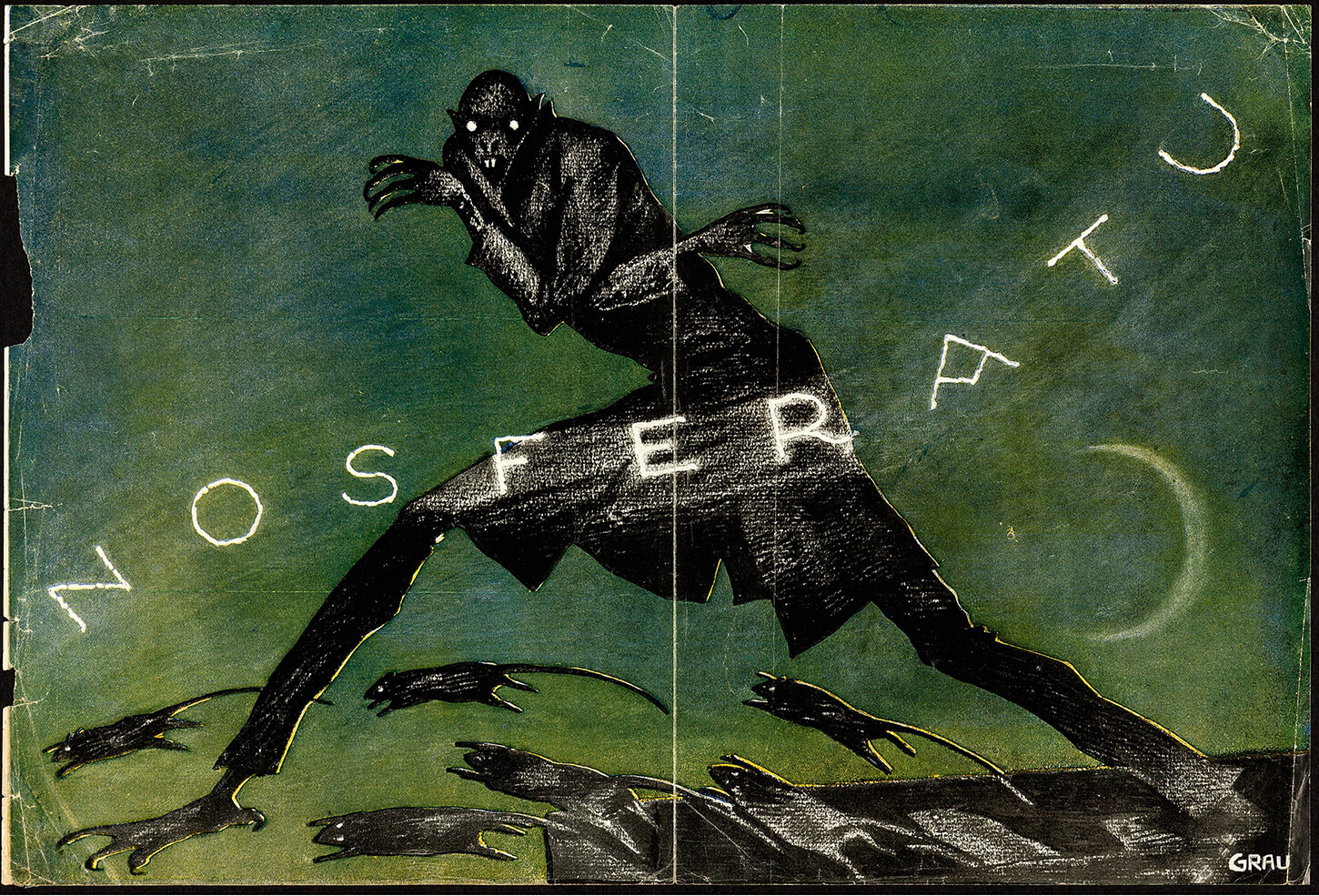

If we can linger with Grau for a moment, how would you contextualize the posters he designed to promote the film? Can you talk about their relation to the history of movie poster design, and how they functioned at the time as a preview of the film, in terms of themes, motifs, or style?

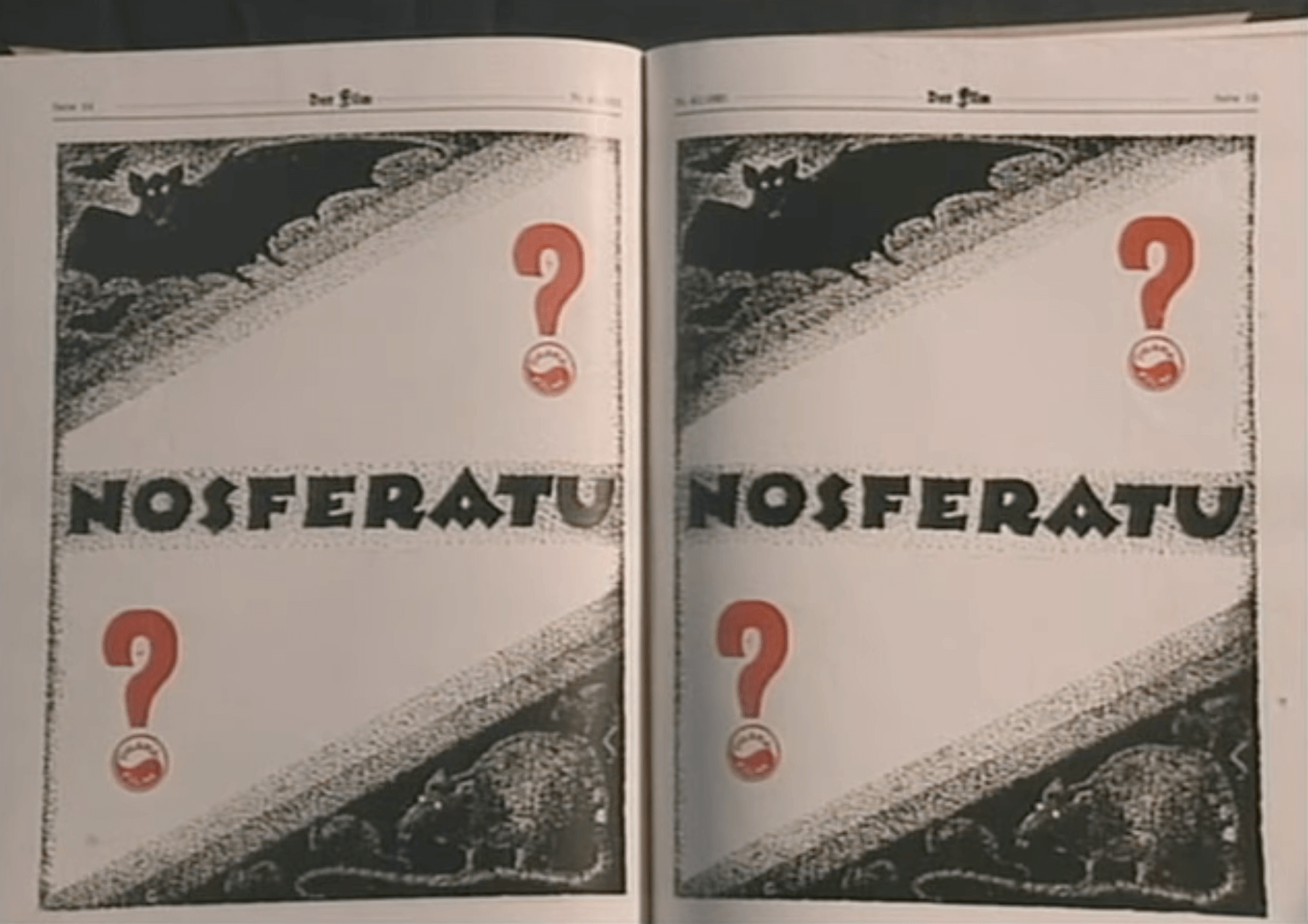

Jürgen Müller: The posters are among the most beautiful film posters of German Expressionism. They are highly suggestive, as Grau succeeds in conveying a monumental impression by showing the vampire from below. The combination of bat, rat and human figure is also ingenious. Grau has succeeded in creating a frighteningly real invention. This design was in the service of advertising for the film and as a commercial artist he was quite familiar with processes of marketing. He staged an extremely costly campaign that in the end also exceeded the financial possibilities of the Prana film company.

Is it true that the marketing and promotion of Nosferatu cost more than the making of the movie? Do you have any sense of what this promotion entailed? Besides Grau’s posters, what are talking about? What was so expensive?

Jürgen Müller: That is a difficult question to which there can be no concrete answer. But in the film magazine Film-Hölle there is talk of dubious management and unfair business practices that have proved too expensive. There is also a satirical text describing how a person walks through Berlin and goes mad because of the accumulation of posters. You wouldn't write something like that if there had only been a few posters to be found. On the contrary, you have to think of Berlin at that time as the film capital of Europe, with good magazines and a knowledgeable audience.

Jürgen Müller: The posters are among the most beautiful film posters of German Expressionism. They are highly suggestive, as Grau succeeds in conveying a monumental impression by showing the vampire from below. The combination of bat, rat and human figure is also ingenious. Grau has succeeded in creating a frighteningly real invention. This design was in the service of advertising for the film and as a commercial artist he was quite familiar with processes of marketing. He staged an extremely costly campaign that in the end also exceeded the financial possibilities of the Prana film company.

Is it true that the marketing and promotion of Nosferatu cost more than the making of the movie? Do you have any sense of what this promotion entailed? Besides Grau’s posters, what are talking about? What was so expensive?

Jürgen Müller: That is a difficult question to which there can be no concrete answer. But in the film magazine Film-Hölle there is talk of dubious management and unfair business practices that have proved too expensive. There is also a satirical text describing how a person walks through Berlin and goes mad because of the accumulation of posters. You wouldn't write something like that if there had only been a few posters to be found. On the contrary, you have to think of Berlin at that time as the film capital of Europe, with good magazines and a knowledgeable audience.

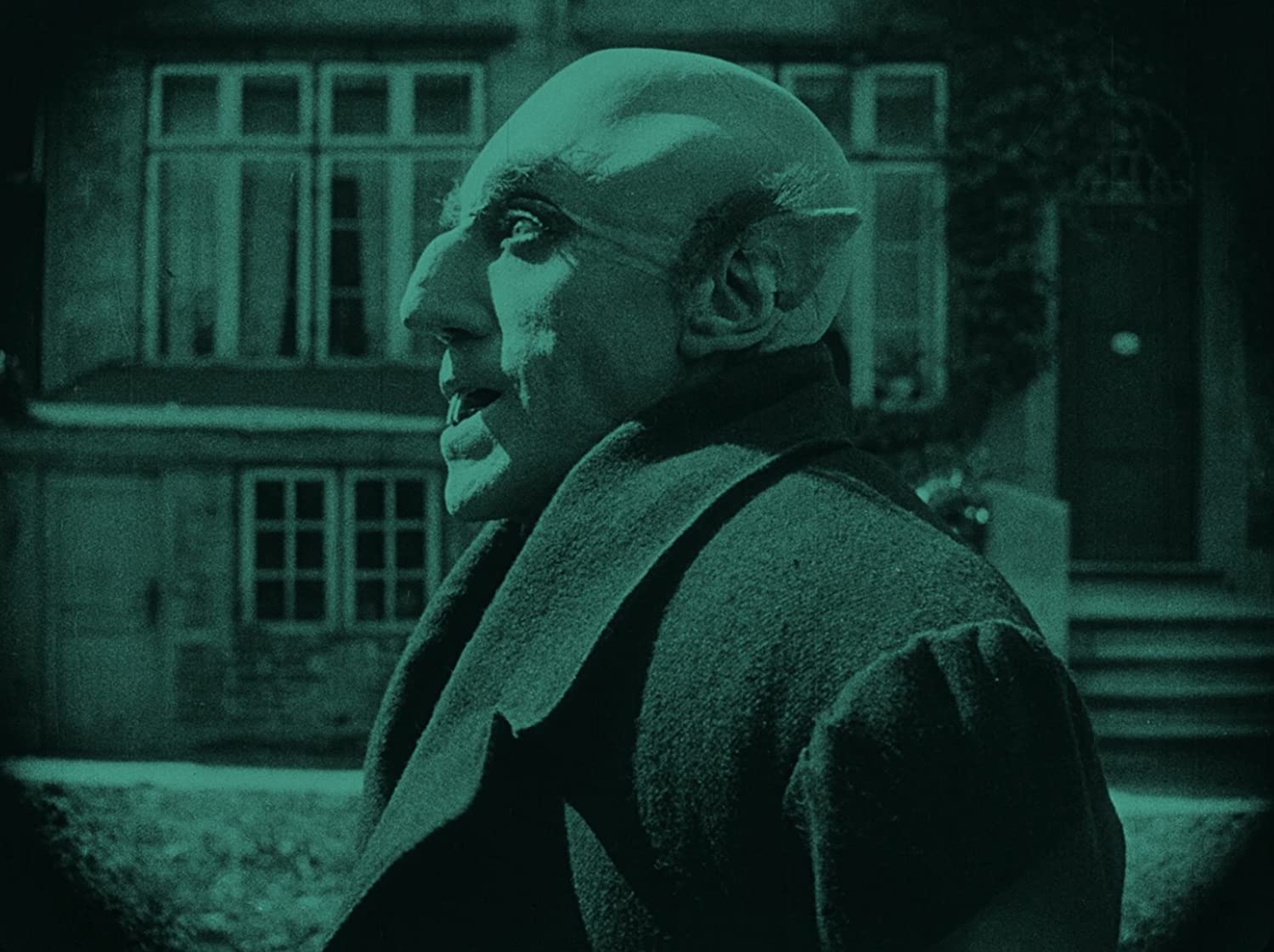

How would you describe the character design (make-up, costume, physiognomy, performance style) of Count Orlok — Nosferatu? If this film is based on Dracula, where did this particular character design come from?

Frank Schmidt: The design of Orlok is perhaps the greatest deviation from the literary model and later adaptations of the novel. This applies not only to the appearance but also to the character’s behaviour. Thus, unlike Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee, Murnau’s vampire is not a superficially elegant seducer who subdues his female victims with hypnotic practices; rather, much about him is reminiscent of a predator.

Frank Schmidt: The design of Orlok is perhaps the greatest deviation from the literary model and later adaptations of the novel. This applies not only to the appearance but also to the character’s behaviour. Thus, unlike Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee, Murnau’s vampire is not a superficially elegant seducer who subdues his female victims with hypnotic practices; rather, much about him is reminiscent of a predator.

When the count welcomes Hutter to his castle, for example, he steps out of the darkness with folded arms and pattering steps, moving like an insect. This impression is already implied in Henrik Galeen’s script, where Orlok is compared several times to spiders and bats. In this way, Nosferatu, like many vampire films after it, picks up on the creatures’ ability to shapeshift; in Murnau’s work, however, this is primarily conveyed through the character’s appearance and behaviour.

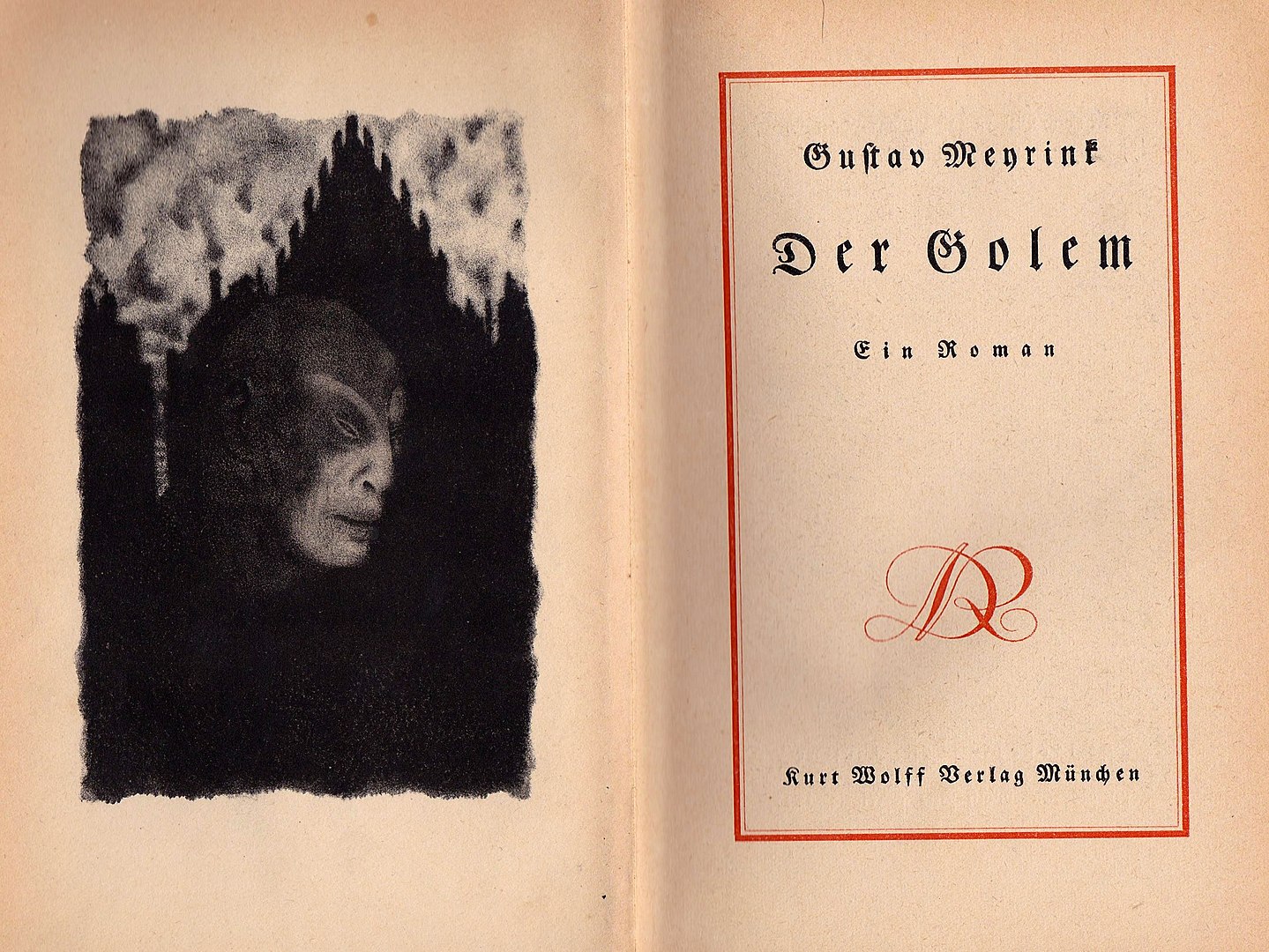

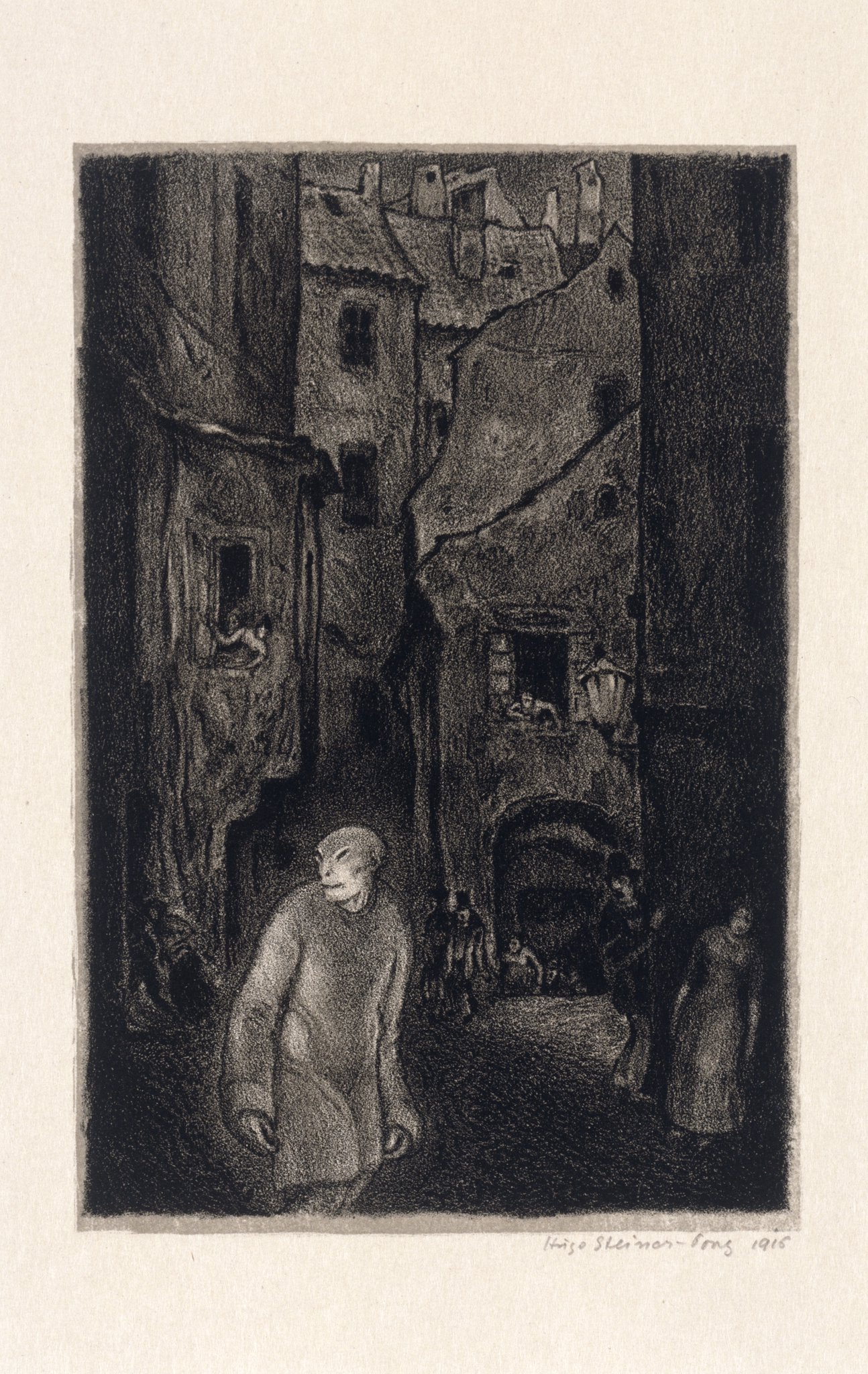

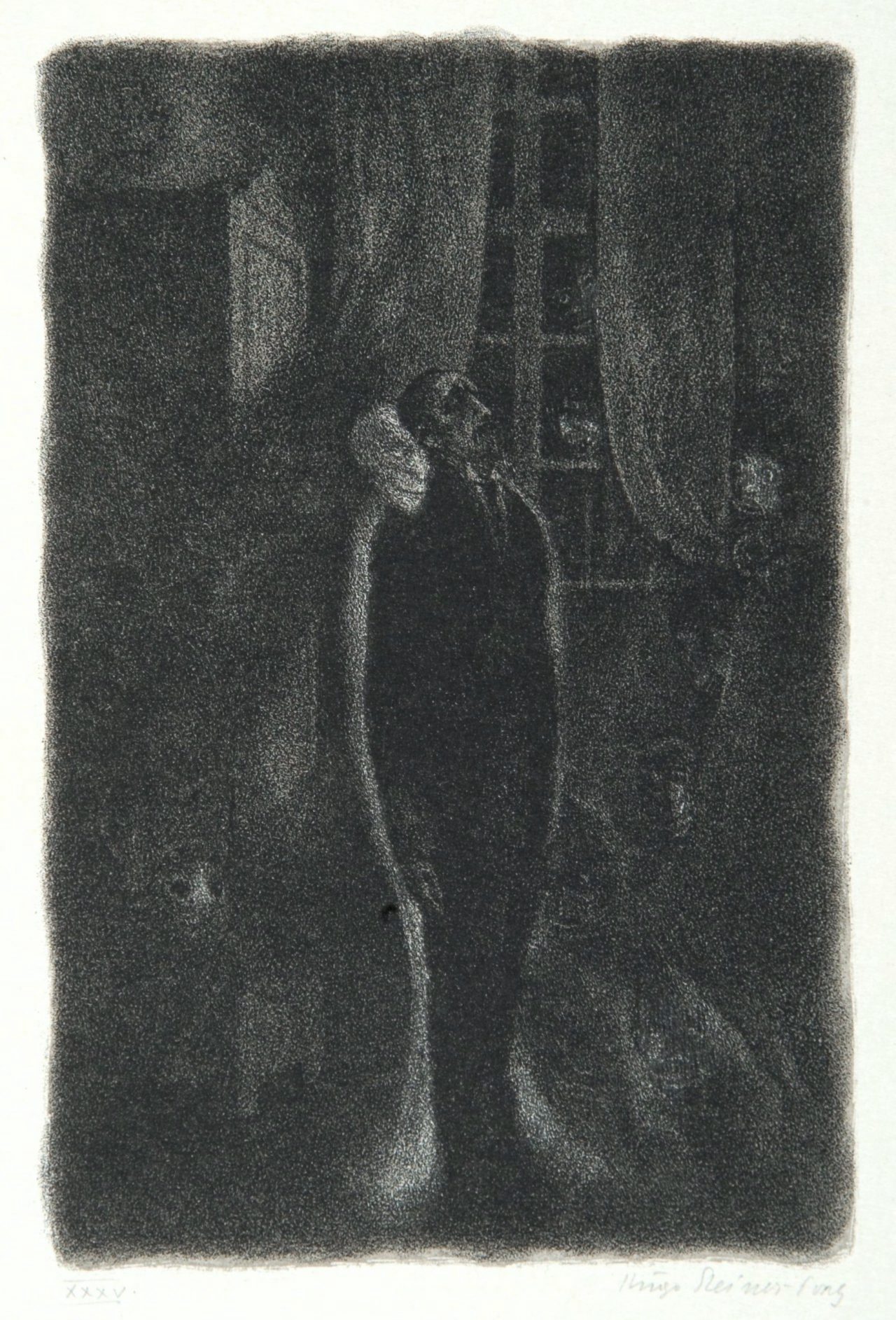

As far as Orlok’s physiognomy is concerned, there are also astonishing parallels to works of fantastic art of the time. Hugo Steiner-Prag’s illustrations for Gustav Meyrink’s novel Der Golem are a good example; a 1913 drawing by Franz Sedlacek and several works by Kubin also show figures that virtually prefigure Orlok’s appearance.

As far as Orlok’s physiognomy is concerned, there are also astonishing parallels to works of fantastic art of the time. Hugo Steiner-Prag’s illustrations for Gustav Meyrink’s novel Der Golem are a good example; a 1913 drawing by Franz Sedlacek and several works by Kubin also show figures that virtually prefigure Orlok’s appearance.

Remarkably, the uncanny design did not find any imitators for a long time – and if you think of the first film adaptation of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, the makers around director Tobe Hooper only resurrected it because it seemed so frightening.

![Salem's Lot (Tobe Hooper, 1979)]()

Nosferatu was made shortly after the Spanish Flu epidemic, which infected 500 million people, killing 20-50 million. Do you have any sense of how this may have impacted the thematic concerns or design of the film? This is a question about virus, contagion, and representation.

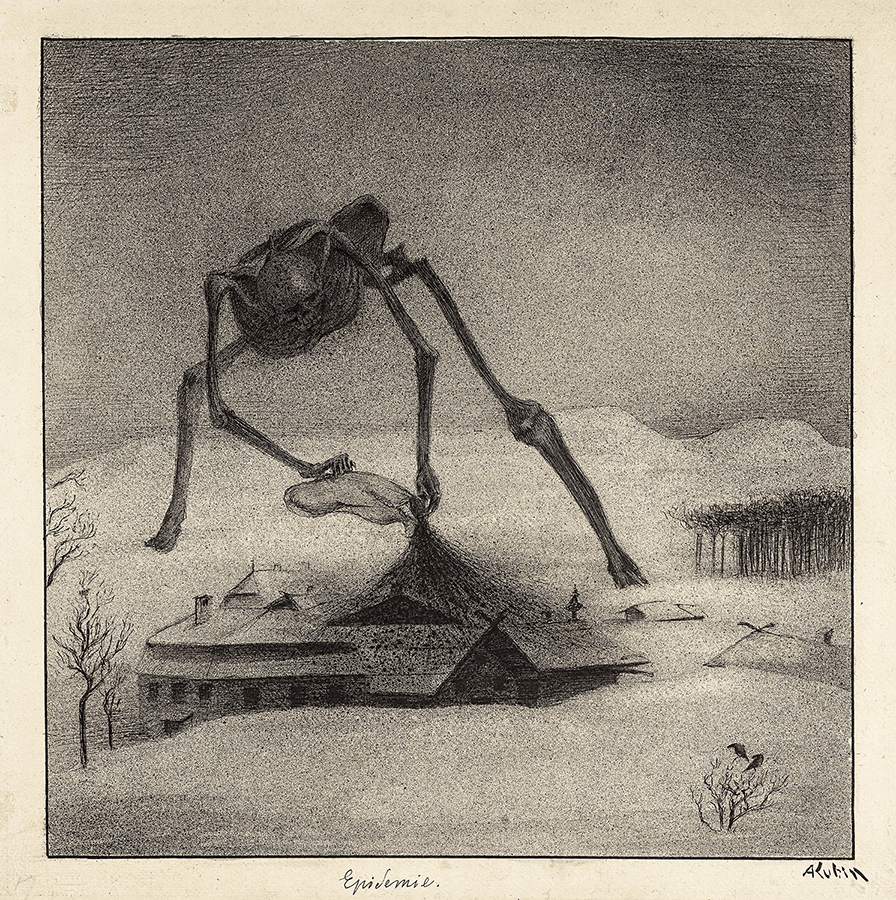

Frank Schmidt: In addition to influenza, typhus epidemics also played a major role and were rampant in Europe during and after the First World War. The fear of the diseases and their suspected carriers aroused xenophobic and anti-Semitic resentment at the time, which, when one thinks of the figure of the vampire and the plague that broke out with his arrival, were fundamental to the conception of Nosferatu. (Without wanting to make compulsive references to the present, it is interesting to note how conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus were similarly popular in connection with the current pandemic.)

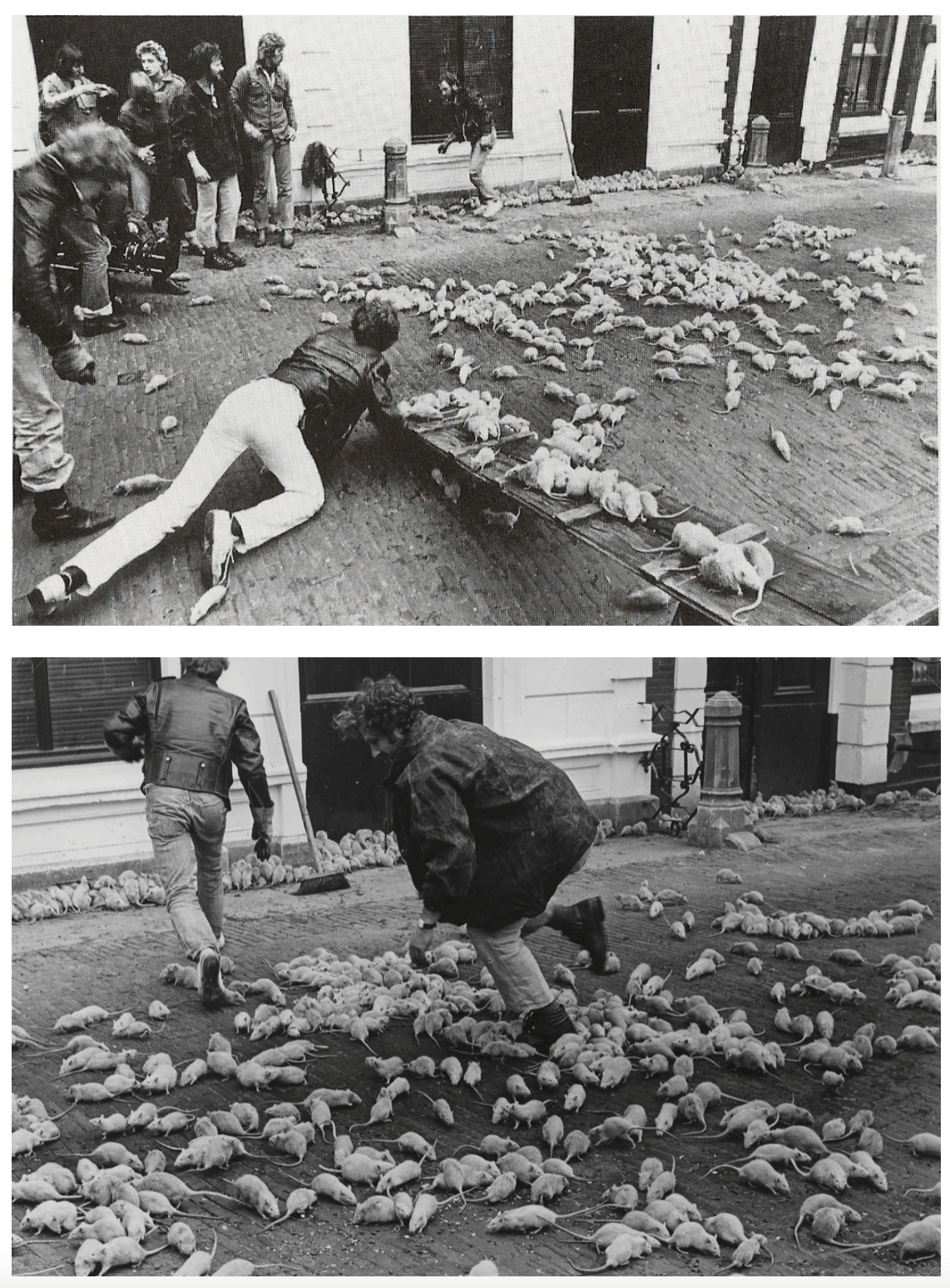

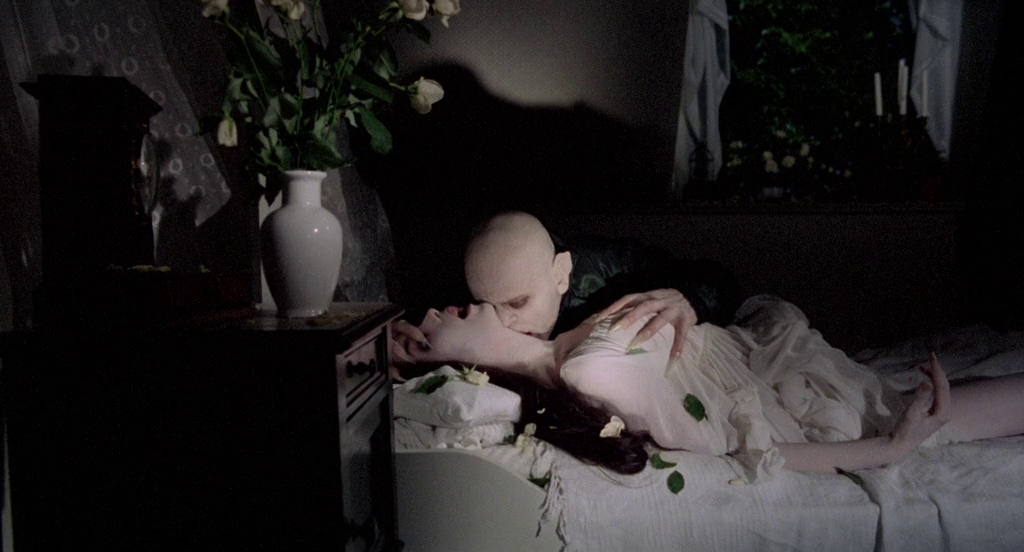

Interestingly, Werner Herzog interpreted this aspect quite differently in his 1979 homage Nosferatu the Vampyre. In his work, illness and death appear as a universal part of human experience, present subliminally long before the arrival of the vampire. The protagonists of his film confront the danger of the plague and the surreally multiplying rats individually – by defying the disease and gathering in the marketplace for a danse macabre.

Frank Schmidt: In addition to influenza, typhus epidemics also played a major role and were rampant in Europe during and after the First World War. The fear of the diseases and their suspected carriers aroused xenophobic and anti-Semitic resentment at the time, which, when one thinks of the figure of the vampire and the plague that broke out with his arrival, were fundamental to the conception of Nosferatu. (Without wanting to make compulsive references to the present, it is interesting to note how conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus were similarly popular in connection with the current pandemic.)

Interestingly, Werner Herzog interpreted this aspect quite differently in his 1979 homage Nosferatu the Vampyre. In his work, illness and death appear as a universal part of human experience, present subliminally long before the arrival of the vampire. The protagonists of his film confront the danger of the plague and the surreally multiplying rats individually – by defying the disease and gathering in the marketplace for a danse macabre.

If it's fair to say that vampire narratives are often in some way about sexuality, how would you describe the way this is handled in Nosferatu? Is this a theme in your exhibition?

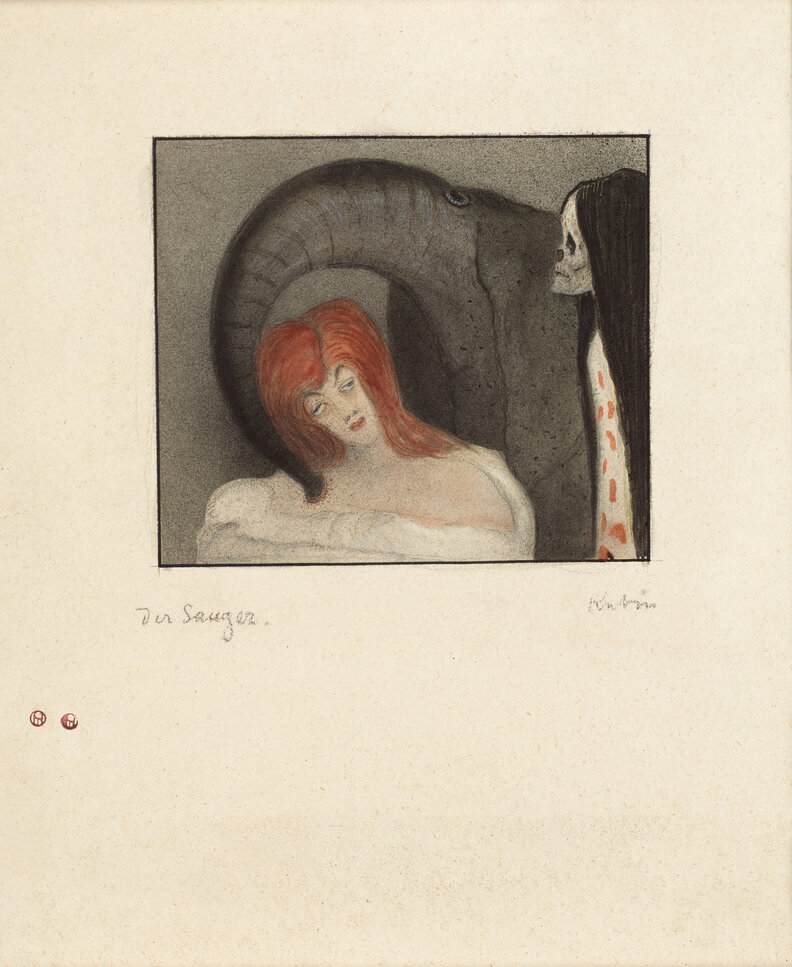

Frank Schmidt: You’re right, the vampire’s bite is of course a sexual metaphor. Accordingly, a chapter of the exhibition is dedicated to the implications of this. The Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection also includes Alfred Kubin’s drawing Der Sauger (The Sucker), in which a leech like creature has attached itself to a woman’s upper body. In addition, works by Félicien Rops are shown, an artist who was known for his explicit sexual depictions and whom Albin Grau named in an article as a decided role model of an “intellectual film.”

Apart from this, Nosferatu is perhaps the most decidedly unerotic vampire film of all time. This of course has to do with the appearance of the vampire, which is in complete contrast to the character established by Bela Lugosi, but also to Stoker’s Dracula. Responsible for this is the fact that Max Schreck’s vampire is less reminiscent of a human being than an animal creature whose teeth are those of a rat. And although the bite is made recognisable by marks on the necks of his victims, the actual process takes place largely outside our perception.

Frank Schmidt: You’re right, the vampire’s bite is of course a sexual metaphor. Accordingly, a chapter of the exhibition is dedicated to the implications of this. The Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection also includes Alfred Kubin’s drawing Der Sauger (The Sucker), in which a leech like creature has attached itself to a woman’s upper body. In addition, works by Félicien Rops are shown, an artist who was known for his explicit sexual depictions and whom Albin Grau named in an article as a decided role model of an “intellectual film.”

Apart from this, Nosferatu is perhaps the most decidedly unerotic vampire film of all time. This of course has to do with the appearance of the vampire, which is in complete contrast to the character established by Bela Lugosi, but also to Stoker’s Dracula. Responsible for this is the fact that Max Schreck’s vampire is less reminiscent of a human being than an animal creature whose teeth are those of a rat. And although the bite is made recognisable by marks on the necks of his victims, the actual process takes place largely outside our perception.

Can you highlight any discoveries from your exhibition research? I wonder how preparing for this exhibition may have impacted the way you understand the themes or art historical legacy of Nosferatu?

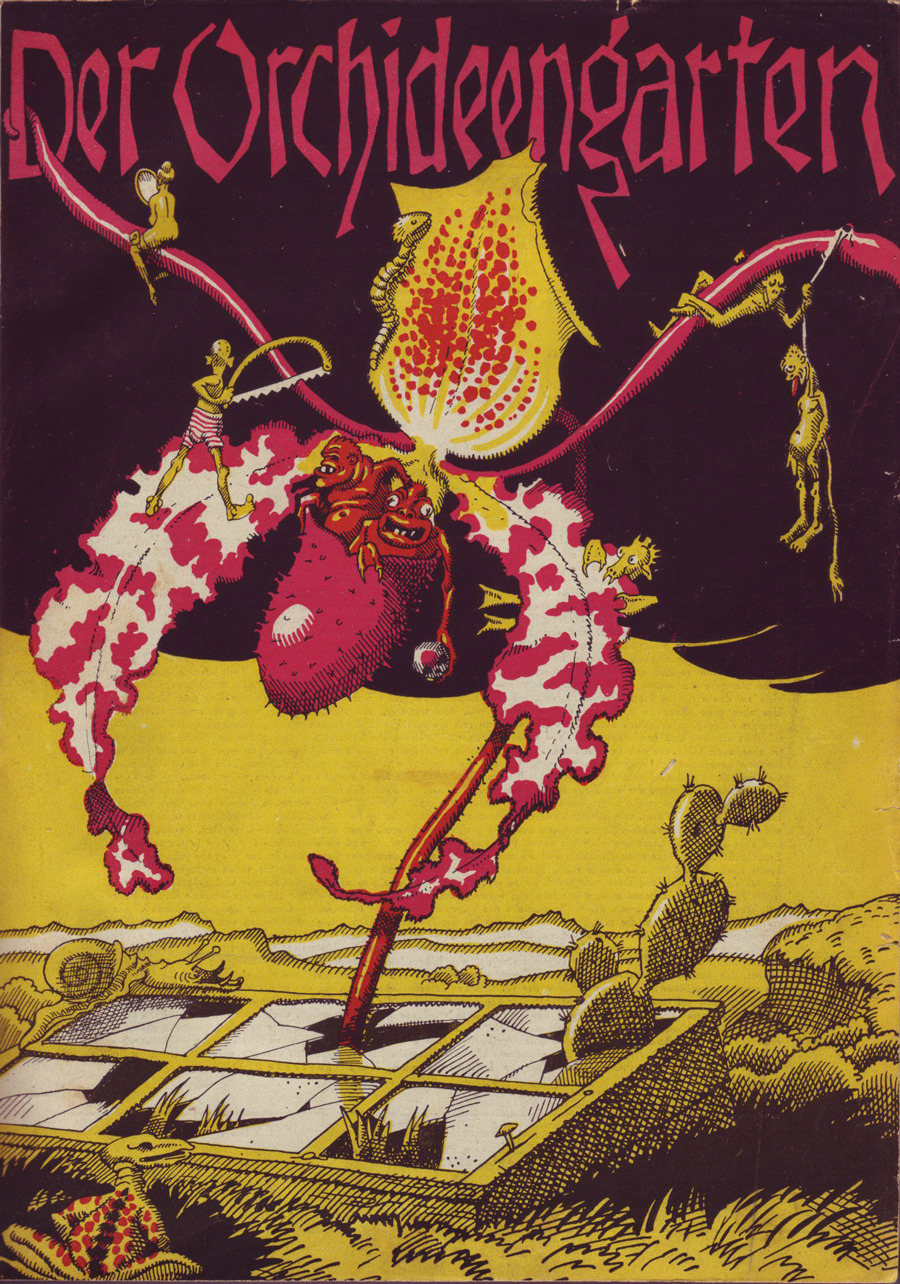

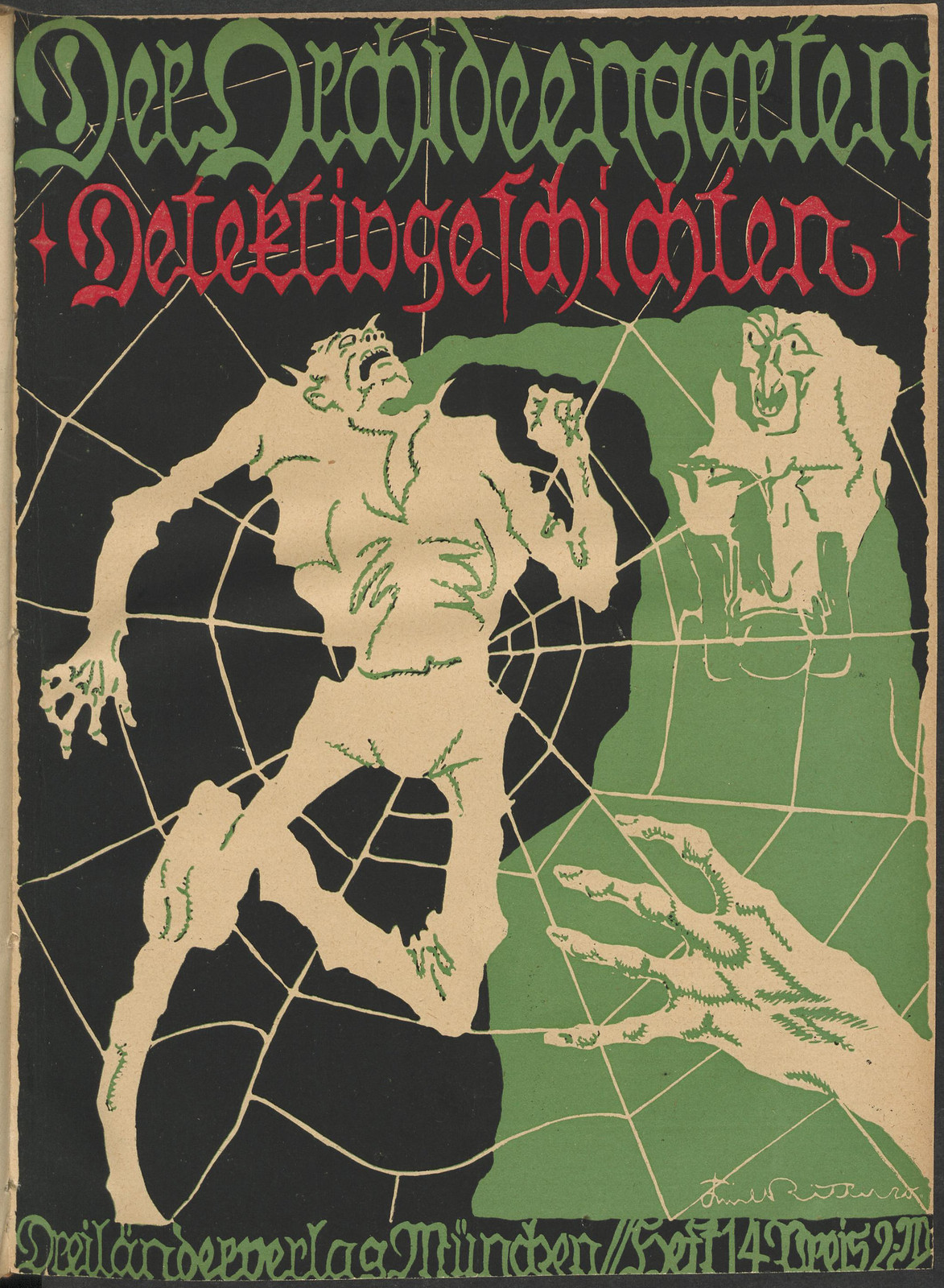

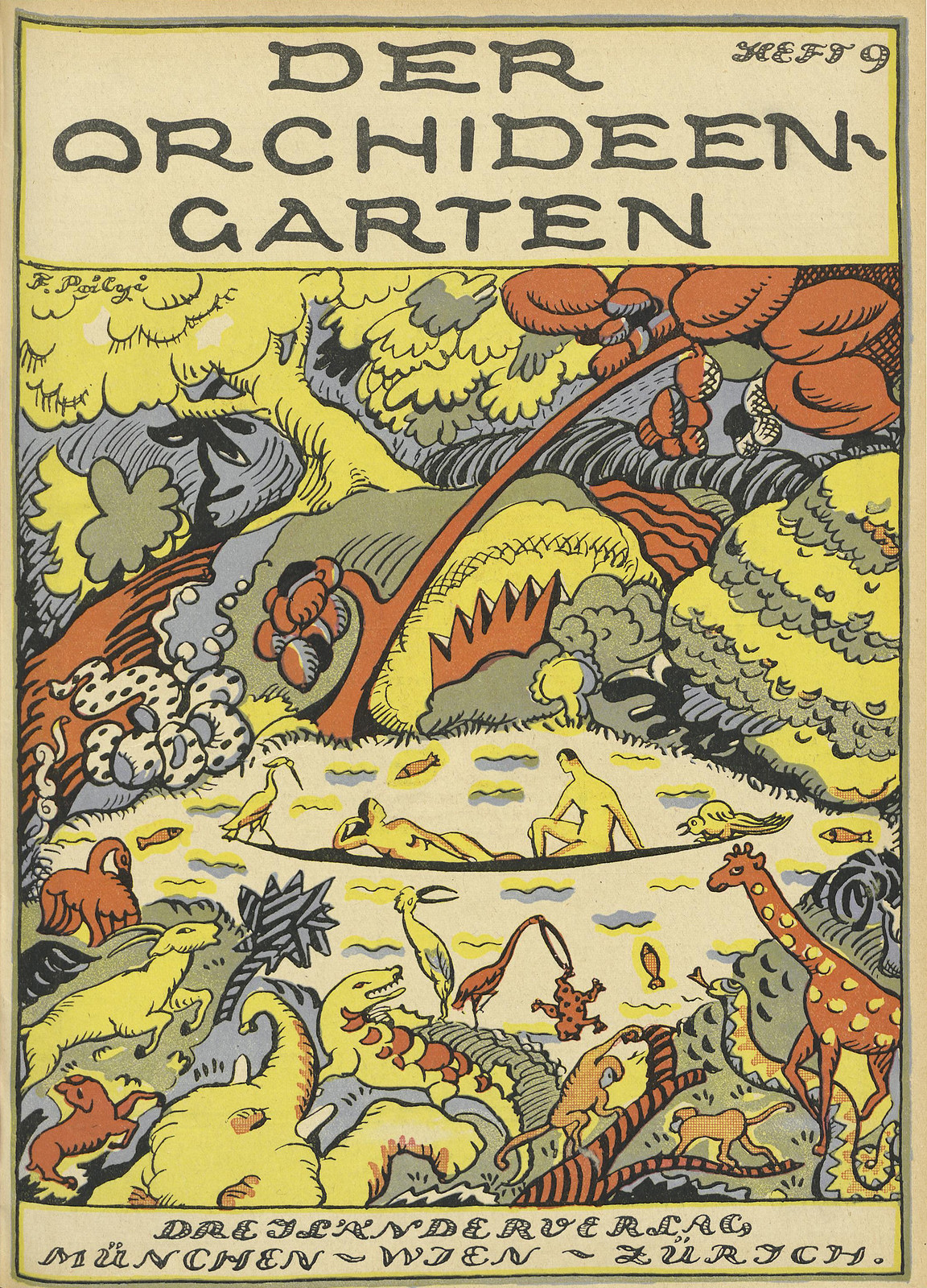

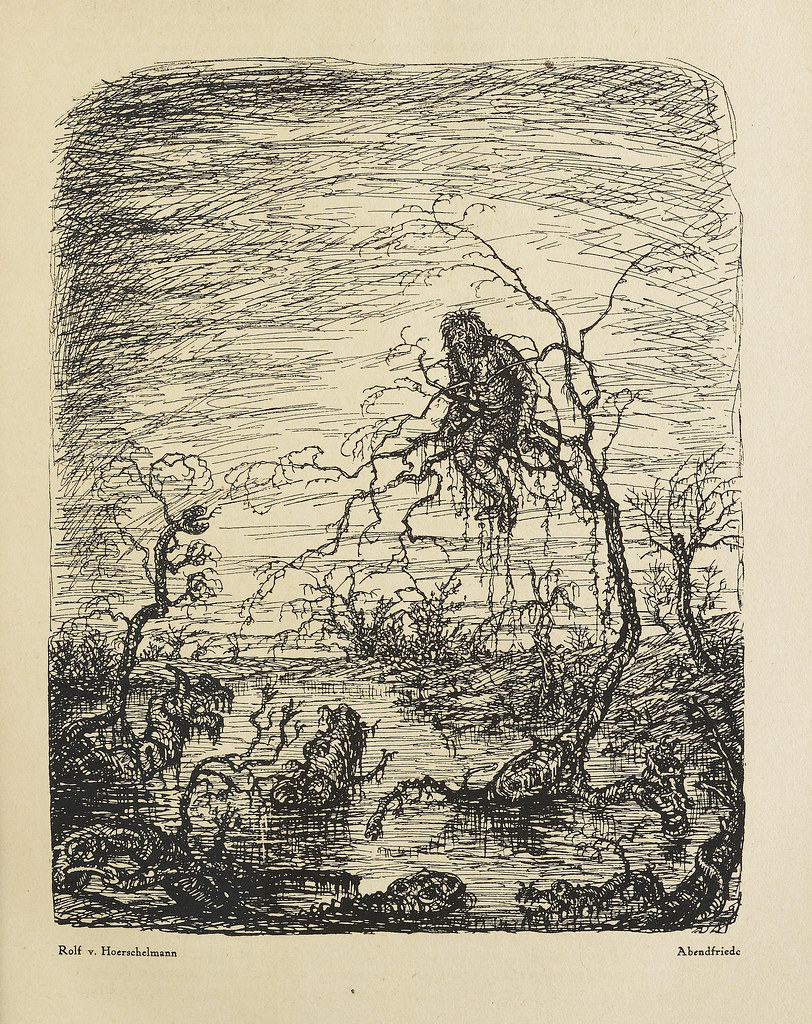

Frank Schmidt: It was exciting to see how great the enthusiasm for the fantastic was at the beginning of the 1920s. For example, from 1919 to 1921, a magazine called Der Orchideengarten (The Orchid Garden) was published in Munich that was dedicated to fantastic art and literature. Numerous films, often lost today, in which Murnau and Galeen, the makers of Nosferatu, were also involved, also bear witness to this enthusiasm. In the course of the preparations, we were also surprised by how familiar Albin Grau was with the fantastic art of his time — and especially with the work of Alfred Kubin. In the course of our examination of the Nosferatu resurrection, we also came across numerous reincarnations in various media; accordingly, in addition to the cinematic reception (the catalogue also deals with the character’s survival in comics).

Frank Schmidt: It was exciting to see how great the enthusiasm for the fantastic was at the beginning of the 1920s. For example, from 1919 to 1921, a magazine called Der Orchideengarten (The Orchid Garden) was published in Munich that was dedicated to fantastic art and literature. Numerous films, often lost today, in which Murnau and Galeen, the makers of Nosferatu, were also involved, also bear witness to this enthusiasm. In the course of the preparations, we were also surprised by how familiar Albin Grau was with the fantastic art of his time — and especially with the work of Alfred Kubin. In the course of our examination of the Nosferatu resurrection, we also came across numerous reincarnations in various media; accordingly, in addition to the cinematic reception (the catalogue also deals with the character’s survival in comics).

It’s interesting that Murnau trained as an art historian before making movies. Do you see any evidence of this in his approach to Nosferatu? Or how would you situate the film in terms of its broader, art historical lineage?

Jürgen Müller: In the original script used by Murnau during filming, there is a handwritten note by the director in which he refers to a painting by Georg Friedrich Kersting, a contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich. But there is only this one passage.

In his fundamental monograph on Murnau, Luciano Berriatúa wanted to find a model in 19th century art for almost every shot in the film. I think this is somewhat exaggerated. Murnau certainly knew his way around because he was generally an educated man. However, I would rather assume that the director uses key images. (I have also tried to explain this in an essay.) All German directors of the silent film era perceived themselves in the tradition of the fine arts. Fritz Lang, for example, spoke of himself as a painter, and Lubitsch based his film "Anne Boleyn" on paintings by Holbein. Max Reinhardt's theatre, to which all these artists were committed, repeatedly used visual effects.

The second part of my answer concerns cinema as a collective art form. Galeen, Grau and Murnau worked closely together. It is a transfiguration of this process of creation to describe the director as the mastermind. That makes films more marketable, but the work takes place in a group and not in a quiet chamber.

Jürgen Müller: In the original script used by Murnau during filming, there is a handwritten note by the director in which he refers to a painting by Georg Friedrich Kersting, a contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich. But there is only this one passage.

In his fundamental monograph on Murnau, Luciano Berriatúa wanted to find a model in 19th century art for almost every shot in the film. I think this is somewhat exaggerated. Murnau certainly knew his way around because he was generally an educated man. However, I would rather assume that the director uses key images. (I have also tried to explain this in an essay.) All German directors of the silent film era perceived themselves in the tradition of the fine arts. Fritz Lang, for example, spoke of himself as a painter, and Lubitsch based his film "Anne Boleyn" on paintings by Holbein. Max Reinhardt's theatre, to which all these artists were committed, repeatedly used visual effects.

The second part of my answer concerns cinema as a collective art form. Galeen, Grau and Murnau worked closely together. It is a transfiguration of this process of creation to describe the director as the mastermind. That makes films more marketable, but the work takes place in a group and not in a quiet chamber.

One of the aims of your exhibition is to document the influence Nosferatu had on the French Surrealists. Which aspects of the film did the Surrealists emphasize? Or are there any Surrealist artworks that demonstrate the influence of Nosferatu?

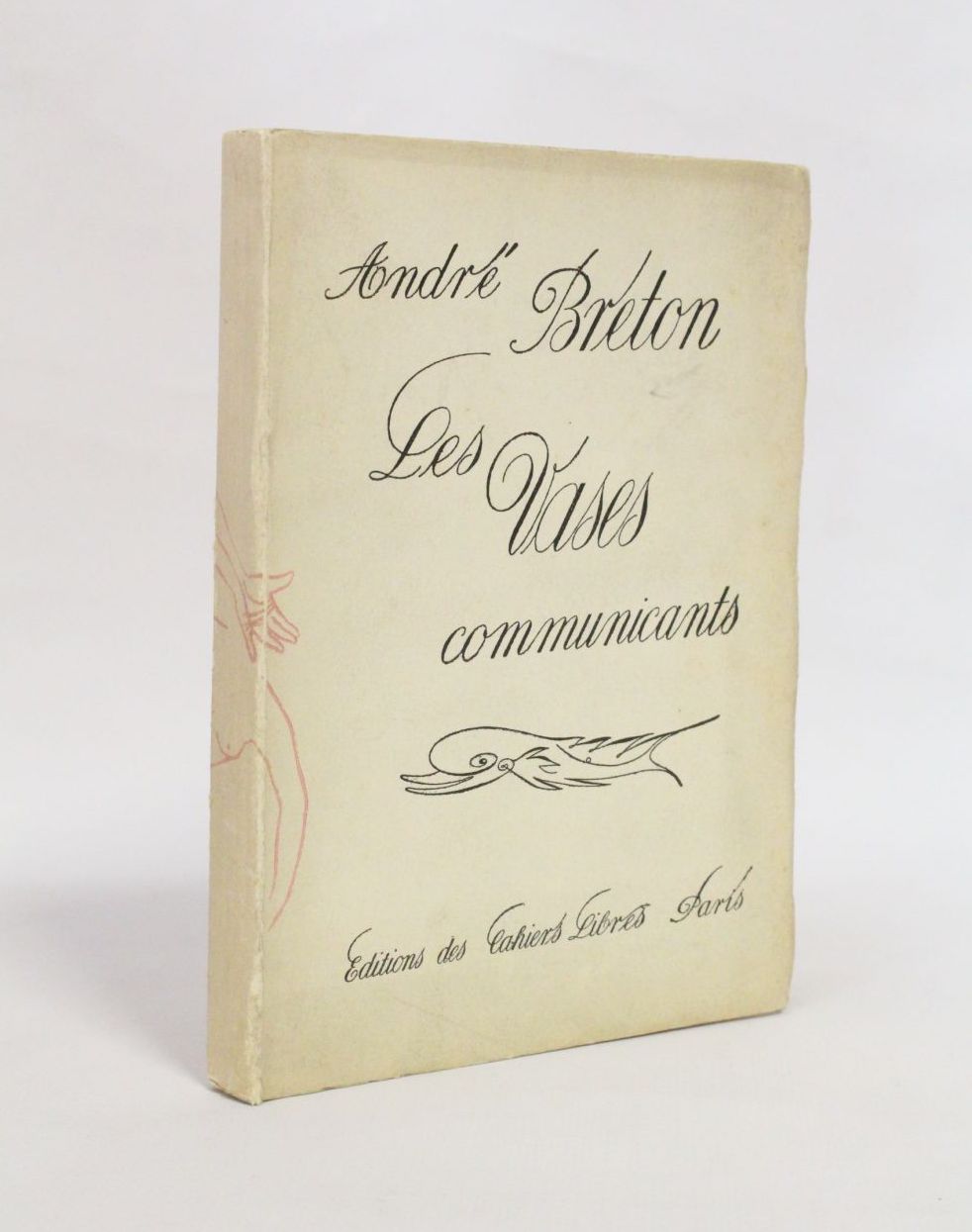

Kyllikki Zacharias: Nosferatu was one of the surrealists’ favorite movies, especially André Breton. In his book Les vases communicants from 1932 he describes a dream of Nosferatu appearing on a necktie he choose in a shop – the blurred outlines of the vampire’s face being similar to the boundaries of France. Breton loved also to quote one of the crucial intertitles of the film: “When he was on the other side of the bridge, the ghosts came to meet him.”(«Quand il fut de l'autre côté du pont, les fantômes vinrent à sa rencontre.»)

Kyllikki Zacharias: Nosferatu was one of the surrealists’ favorite movies, especially André Breton. In his book Les vases communicants from 1932 he describes a dream of Nosferatu appearing on a necktie he choose in a shop – the blurred outlines of the vampire’s face being similar to the boundaries of France. Breton loved also to quote one of the crucial intertitles of the film: “When he was on the other side of the bridge, the ghosts came to meet him.”(«Quand il fut de l'autre côté du pont, les fantômes vinrent à sa rencontre.»)

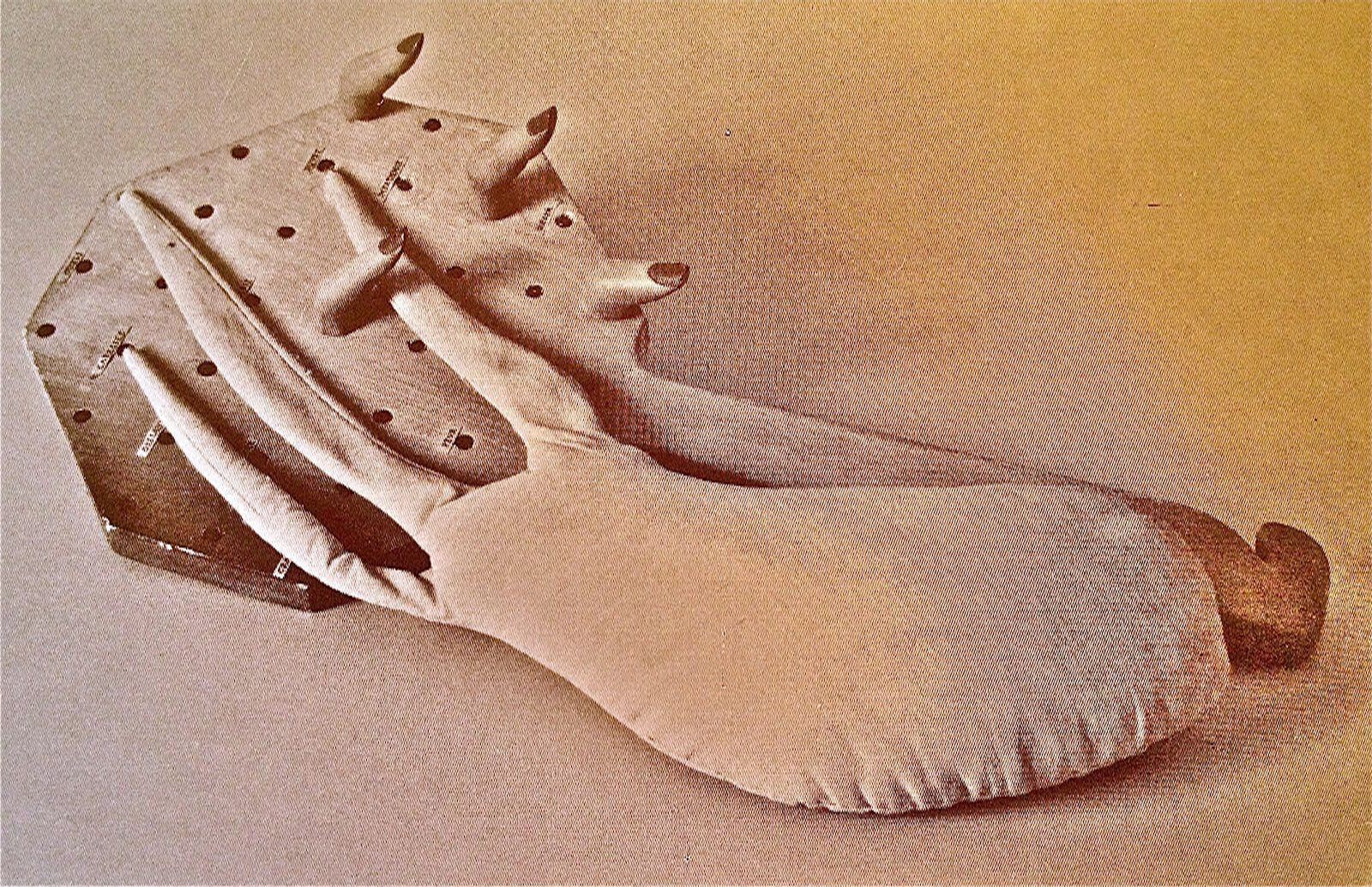

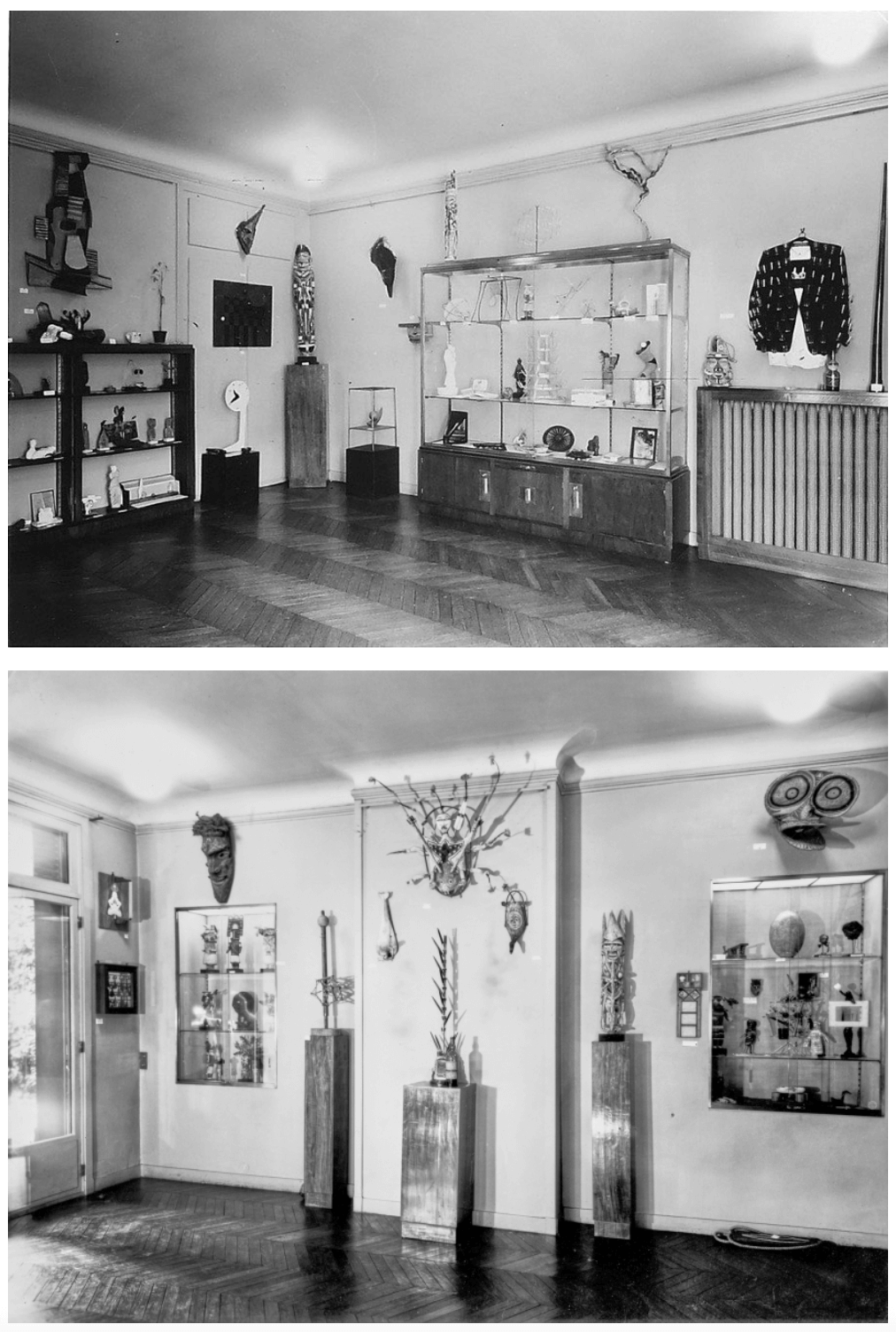

Four years later, in 1936, Yves Tanguy exhibits an object with the title “De l’autre coté du pont” (on the other side of the bridge) — a reference to Nosferatu — at the Surrealist Objects exhibition Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris. There will be an article from me about this and other examples in the catalogue.

Finally, can you tell us about one of your favorite artworks from the upcoming exhibition? And what do you hope audiences will discover when visiting the show?

Jürgen Müller: Hugo Steiner-Prag's illustrations of Gustav Meyrink’s Golem. These live from the artist’s ability to dissolve reality into schemata in order to demonstrate the power of darkness.

Jürgen Müller: Hugo Steiner-Prag's illustrations of Gustav Meyrink’s Golem. These live from the artist’s ability to dissolve reality into schemata in order to demonstrate the power of darkness.

Frank Schmidt: It is remarkable to see the pictorial power that Albin Grau’s designs still have a hundred years after they were created. The advertising campaign, for example, envisaged an individual poster motif for each of Berlin’s major squares. The surviving watercolours alone are worth a visit to the exhibition.

Personally, I am also looking forward to the works by artists who, for various reasons, have not received as much attention as Kubin. These include his contemporaries Franz Sedlacek and Stefan Eggeler, whose compositions show an astonishing closeness when juxtaposed with Nosferatu.

Personally, I am also looking forward to the works by artists who, for various reasons, have not received as much attention as Kubin. These include his contemporaries Franz Sedlacek and Stefan Eggeler, whose compositions show an astonishing closeness when juxtaposed with Nosferatu.